Today on Art of the Cut, a little change of pace.

August 2023 was the 30th anniversary of the movie, The Fugitive, directed by Andrew Davis and edited by Don Brochu, David Finfer, Dean Goodhill, Dov Hoenig, Richard Nord, and Dennis Virkler. Why so many editors? You’ll soon find out as I talk to director Andrew Davis about the evolution of the film through editing, his thoughts on being one of the first directors to try to cut a film using Avid Media Composer, and what he looks for when choosing a new editor for a project.

Mr. Davis was nominated for a Golden Globe and a DGA Award for Best Direction for The Fugitive. His other films include Under Siege, Chain Reaction, A Perfect Murder, Collateral Damage, Holes, and The Guardian.

30th Anniversary of The Fugitive with director, Andrew Davis

There’s a crazy coincidence between The Fugitive and my early editing career. The second Avid I ever worked on was used to edit The Fugitive. I worked at a place called Del Hall Video - a post house in Chicago - and the Avid was purchased (back when Avid systems were well over $100K and had 3 2gig hard drives) - and rented to the production while they were in Chicago. One of the things left over when I started working on that system was the continuity document for the movie. My old boss Del said that the two of you kind of ran in the same circles back in the late 1960s.DAVIS: I just remember Del as someone who was in the world of Chicago filmmaking when I was an assistant cameraman doing commercials and documentaries and working with all kinds of people, from Walt Topel to Gordon Wiesenborn to Mike Gray and Jim Dennet. I was an assistant cameraman to Frank Miller, who later became an operator on many of my movies. It was a great group of Chicago filmmakers in 1968 when I started working in that world. And so I just remembered Del as a respected cameraman. I don't remember anything about the fact that Del bought the Avids for us to use. I think that it was just coming in. Nobody really knew how to use it. And Dean Goodhill was a guy who said, “I want to bring the technical world of the Avid into your cutting room.” I don't know how we decided to say yes and do that, but it arrived. Dean wound up working on it. It never really went that far.

I think Dean Goodhill might agree about the Avid issues. He wrote this to me:It’s a fact that we took a lot of liberties with the script and the continuity as Andy originally shot it, but every move we made was supervised by Andy. He gave us a lot of freedom to explore options. I have some vague memory of his saying he wanted us to improvise with the footage, much like a jazz musician, rewriting the script after the fact, but everything we did was cheered on by Andy.

There is much to say about the technical difficulties I experienced because I was working on Avid while my colleagues were still cutting on film. The technology was barely ready for such a large production. Someone in the tech world once said, "you can always tell who the pioneers are because they’re the ones with arrows in their backs.” I got my share of arrows, and some traumatic problems had to be dealt with. Just imagine the challenges of editing a film on an Avid when the largest hard drive available was only 2-gigs.

Anyway, I want to talk about the differences between this continuity document I have, that you can see in the blog version which describes the way the film was scripted - and the way the film ended up in editing. They’re really quite different.The opening of the movie was so complicated and had so many possibilities. And one Saturday, Dennis Virkler came into the cutting room and took all the footage that he had and looked at… what Dean had done with other people, and he put together that amazing opening — pretty much put together the opening. I worked with him on it afterward, but that concept of the flashbacks and the de-saturated black and white and all that, that was Dennis Virkler. So the reality was the Avid didn't really get a chance to do much on The Fugitive. It was cut on film. Everybody had KEMs. I don't think there were any Moviolas being used. There were six different editors. And I would go from room to room like a dentist working with each of them. Don Brochu, Dov Hoenig and Dennis Virkler are the ones I remember making the greatest contributions.

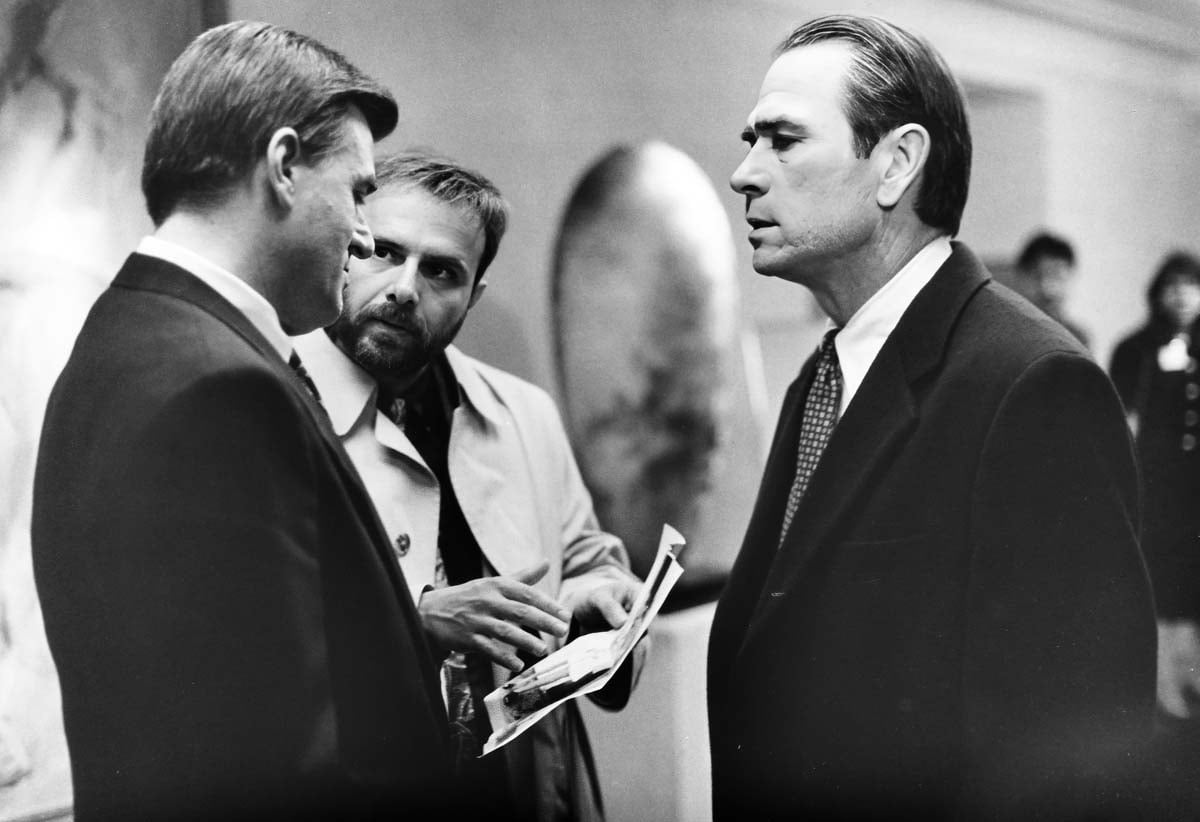

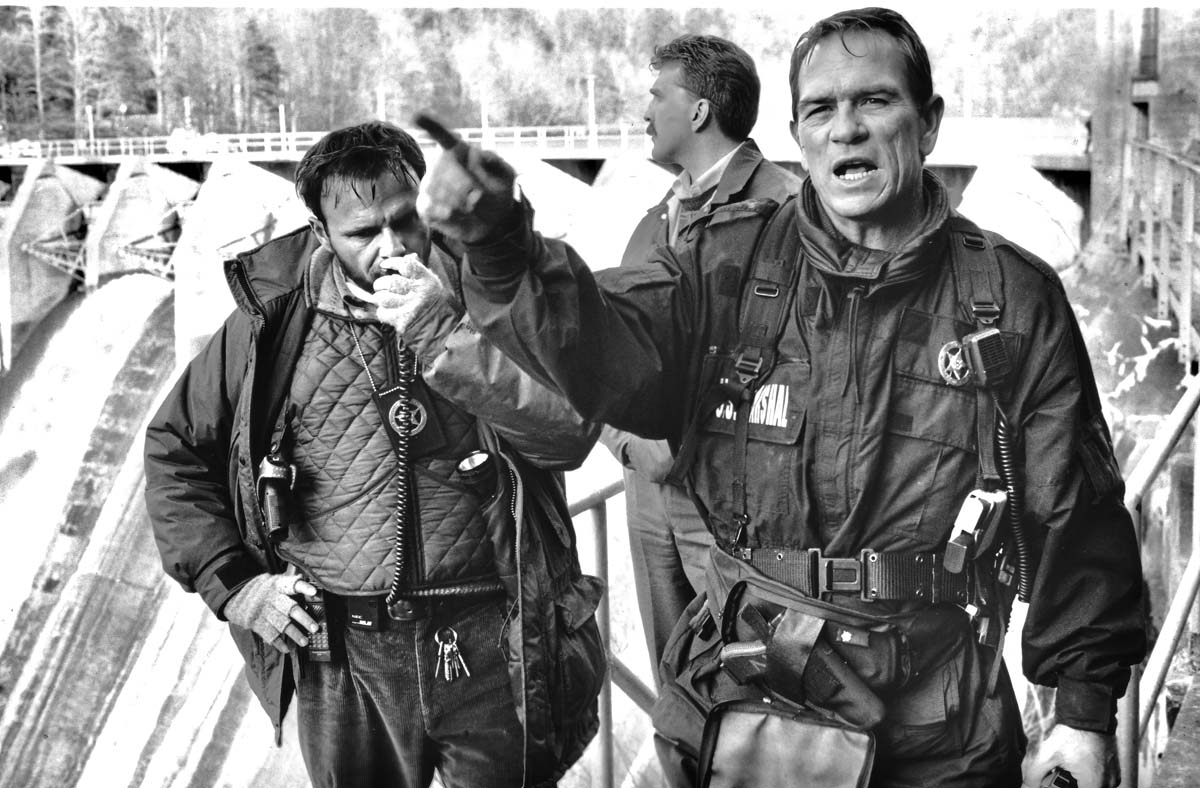

Davis and Tommy Lee Jones. All images in this article, courtesy of Andrew Davis.

The way the film was actually edited — the way that we see it now, 30 years later — that was cut on a KEM.

Davis and Tommy Lee Jones. All images in this article, courtesy of Andrew Davis.

The way the film was actually edited — the way that we see it now, 30 years later — that was cut on a KEM.

Yes.

Very interesting. So I actually have with me a document that I've had for the last 30 years: the continuity of the movie and it is very linear. I don't know how the script was — you would know that.Where did you get that and what date is on it?

The date is April 24th, 1993. I got it when I started my second Avid editing job in 1993 at Del Hall Video in Chicago. I think the movie got released in August of 93.Yeah, so in the middle of the middle of cutting. I don't know what that represents in terms of the script. The script in terms of structure — all the flashbacks to the wife — that was probably created in the cutting room. It wasn't in the script. I saw a comment from her (Sela Ward) recently. She thought she wasn't going to be in the movie, but in fact, the fact that they stretched out her performance and her story gave it more presence.

Sela Ward and Harrison Ford.

Sela Ward’s performance is used in flashbacks all the way through when Harrison Ford’s character dives off the dam into the river. There’s a great cut after Harrison drags himself out of the river and falls asleep in the woods when he dreams of making love to her and it cuts straight from that to him performing CPR on her after the attack, from dream state to nightmare.

Sela Ward and Harrison Ford.

Sela Ward’s performance is used in flashbacks all the way through when Harrison Ford’s character dives off the dam into the river. There’s a great cut after Harrison drags himself out of the river and falls asleep in the woods when he dreams of making love to her and it cuts straight from that to him performing CPR on her after the attack, from dream state to nightmare.

Yeah, that was all created in the cutting room.

So talk to me about the script and the differences in structure and why it needed to change when you got into the cutting room.The script in terms of the words — and a few things that we either added or took out — was going through changes all the time. I knew what the essence of each scene had to be — story-wise, what it had to convey — but sometimes there were words that were fairly appropriate and other times we'd go to the set, take a handful of words and say, “Okay, let's embellish this. Let's give our characters to it. Let's make it better.” And we did that.

For example, the scene where they listened to the bell on the bridge by the river that was all created that morning.

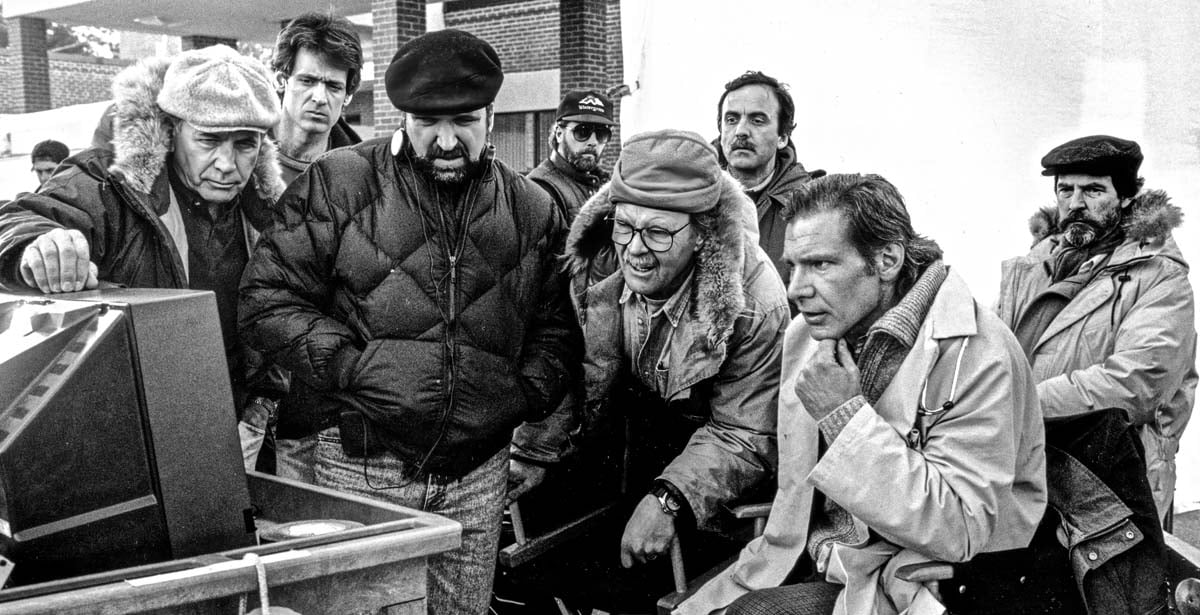

Harrison Ford and Davis at the payphone near the Merchandise Mart on the Chicago River.

That's the scene where Kimble — Harrison Ford's character — is calling from a phone…

Harrison Ford and Davis at the payphone near the Merchandise Mart on the Chicago River.

That's the scene where Kimble — Harrison Ford's character — is calling from a phone…

Payphone. He's calling his lawyers, it’s John Cusack’s father, Dick Cusack — another Chicago filmmaker, who played the lawyer. He's calling Cusack, and they overhear the recording of that and they hear this bell. And then, “Next stop, Merchandise Mart.” So they knew exactly where that was. That was all sort of fabricated: Tommy's funny line, “How did you know that was an L train?”

Character revealed through action.

That's exactly what I think.And there is a great story: there's an eye doctor in Santa Barbara. And on the wall he had a signed poster from a Coen brothers movie, signed, “Dear Dr. So-and-so, you're good for the Jews!” I said, “Why do you have this on the wall?” He said, “Well, I took care of their kid.” This doctor went to Harvard or Yale. He’s an amazing doctor. I said to him, “You know, I made a movie about a doctor once.” He says, “Which one?” I said, “The Fugitive” and he stepped back, and he said, “I was an undergraduate at Harvard, and when I saw that scene where Harrison changes the surgery orders, I decided to become a doctor.”.

Wow!

Wow!

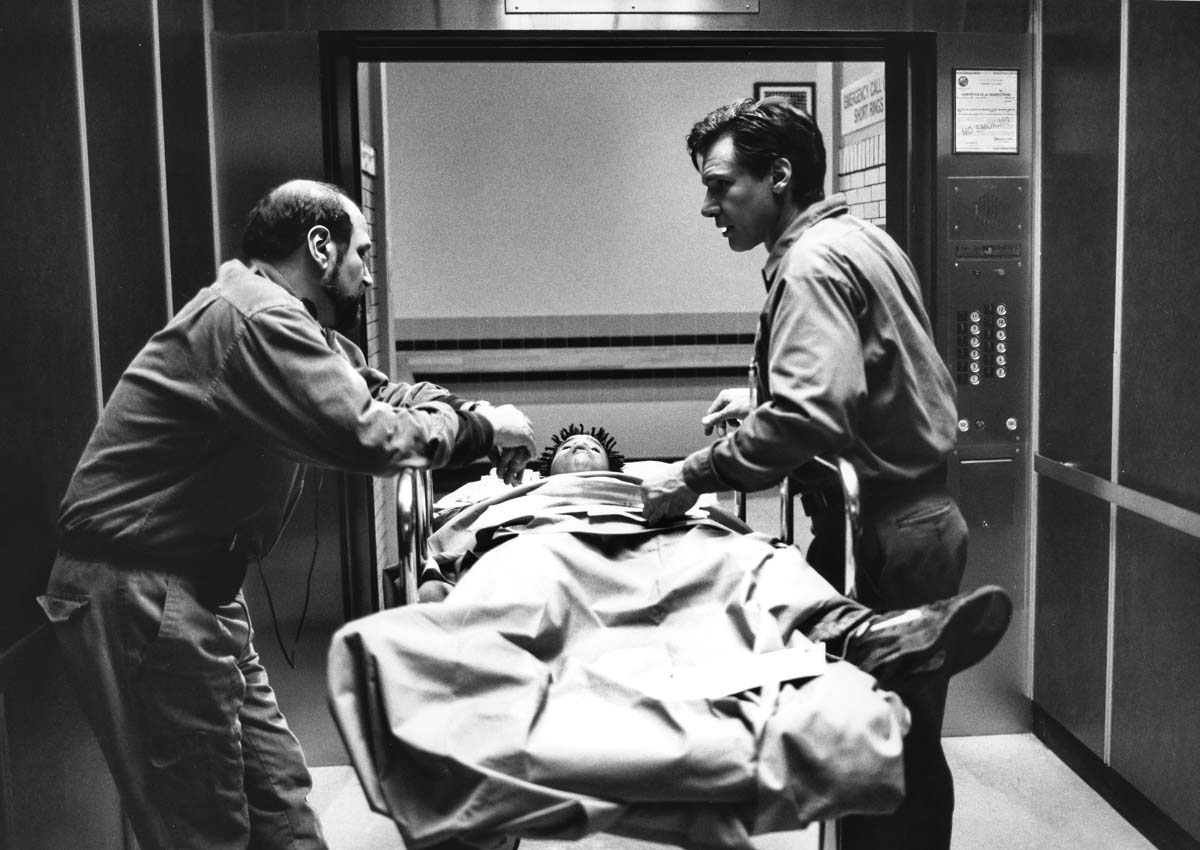

Yeah, It's a powerful scene. It makes me cry still. And the kid on the gurney is the nephew of Stoney Robinson, who's the lead in Stony Island.

I didn't know that. The other thing that I noticed, and I loved how subtle it was, he's walking away and he holds up the x ray, and the female doctor sees it.Julianne Moore.

Julianne Moore sees it, but there's not a big deal made of it. But you see that she notices.Well, there were a lot of people coming and getting hurt. She didn't realize that he changed the orders till later.

Right. And that's another great moment of Tommy Lee's character asking her, “Did the kid make it?” And she says, “He saved his life.” Performance and take choices as a director. With Non-linear editing, it’s easy for me to call up every take and audition them for a director, but not so much back in the KEM/Steenbeck/Moviola days. When you’re trying to decide, Do I trust Dov’s take choice? Do I trust that Don's choice with a take or performance? How does that work?

There may have been notes taken during dailies where it was pretty obvious and clear. We didn't do a lot of coverage. It wasn't like ten takes of one thing or another. A lot of it was performance, but also it was kind of the visual variety. Where do you want to be picture-wise? Everybody sort of got on board with who these characters were, and we didn't argue about. “This line sounds better than this take or this line sounds better than that take.” I don't remember it. A billion details.

Oh yeah. From 30 years ago. Of course.It was pretty clear and obvious to us sitting there together. I would say, “Use that take” or “I like that performance.” Or they would show me something and I’d say, “It looks great, what are the alternatives?” It's an effort. It's a review and a decision.

Back then, there were communal dailies.Oh, yeah, everybody watching it together? Yeah.

Everybody watching together on a big screen instead of, on your laptop or PIX or something. Can you talk about the value of that or what you think's been lost since we've lost that?

What's gained is people are getting more sleep. To finish a 12 or 14 hour day and then get driven to watch the dailies in a dark room. People are going to go to sleep saying, “I don't want to watch any more people driving through the city with second unit.” When it's good, it's celebratory! I remember we were down in North Carolina and we're shooting the train crash and doing the dam and all that kind of stuff. And the crew was pretty worn out, and I think one of my assistants was able to get some footage from the dailies. We had a party on a Friday night. We're staying at a hotel in an Indian reservation, and everybody got together and they showed some footage of the train crash and they all went crazy, so that sort of inspired everybody. So it's a very positive thing when people can see something they've been working on. It comes alive. It gives them more motivation to be with it.

The department heads want to go see. it. Wardrobe wants to see it, makeup wants to see it, the camera crew wants to see if they're in focus. There's a lot of reasons to watch it. I don't remember a lot of actors coming to dailies.

Tell me about your editors. Who they were and why did you select them? What other projects did they work on with you?Well, Dov Hoenig was the guy who cut Stony Island, who I met when I was a cameraman shooting a movie for Menahem Golan with Tony Curtis called Lepke. My first big job as a DP. I was watching some cut footage that Menahem showed me, and it was not well cut. I said, Menahem, you need to get a better editor. He says, “Andy, you’re right, I'm going to bring Dov” and Dov Hoenig came over. Dov had become a very experienced and revered editor. He had cut I Love you Rosa. He was working with Moshe Mizrahi and different French directors. He had gone from Romania to Israel to France. He had done a lot of films for Golan. He brought Dov over and he didn't leave. I remember Michael Mann coming to see a cut of Stony Island, and he hired him to cut Thief. Then he wound up cutting many films. Look up Dov’s credits. So that's number one.

Number two, Dennis Virkler worked with my former girlfriend Mary McGlone on Gorky Park [she was assistant editor] and [co-producer] Peter Macgregor-Scott brought him in because they had worked on a Belushi film together — Continental Divide, I think — or something like that. They worked on a film together and we were working on Under Siege, and the editor wasn't literally cutting it and his attitude was bad and he just didn't have the chops. So Peter said, “We should bring Dennis.” And I said, “Okay.” So Dennis showed up. The film was nominated for Best Sound and we got along really well. Then we brought Dov in to work with Dennis, and Don Brochu was another editor that Peter knew. His wife was the sister of Cheech Marin. And Peter had done a bunch of Cheech and Chong movies.

The funny part is Dennis and Dov had heard about each other's reputations. They were tough in the cutting room. The assistants were treated like dogs, and all this kind of stuff. And they wound up falling in love. Dennis asked Dov to come and work on one of the Batman movies. They had great respect for each other. Don Brochu wound up cutting The Fugitive with Dov and Dennis and the others, Richard Nord and David Finfer and Dean Goodhill, but then Don wound up cutting Steal Big, Steal Little with me. He worked on Chain Reaction. And then I brought another editor and who I really loved, Tom Nordberg, who cut Holes with me, and then wound up cutting The Guardian. Tom worked with Oliver Stone a bunch. He's retired now. He's great a great editor. And he was the wizard of the Avid. He knew how to take the Avid and do visual effects and transitions. It took a while for these other guys to get to know how to do it. I remember Dov — when we were cutting Stony Island — my grandfather was a tailor and he'd have the measuring tape around his neck, and Dov would have the film around his neck. He’d smoke Kents all day long. It was a whole other world. We had a Steenbeck in those days.

Peter Macgregor-Scott and Dennis and I with Dov and sometimes with Don — We're like a post-production team. Peter Macgregor-Scott, I can't give him more accolades about what a brilliant producer he was. He understood post-production so well and how to anticipate things and how to have things ready.

How do you cut and mix The Fugitive in eight weeks if you don't have a genius behind you? We were dubbing on one stage and screening on another stage and pre dubbing and looping, all at once.

What was the purpose or reason for that many editors? Was it just a huge time crunch?Yeah, there was a lot of footage just to go through everything and to be able to get the best out of it. We had a preview of our own. We had 100 people and we knew we had a solid movie. We knew it even before that, but we showed it to the studio. They were all nervous. They didn't know what the hell we were going to do. They saw that Harrison loved it. You’ve probably heard the story that he kissed me and all that shit.

The studio said, “Don't touch it. It's perfect!” And we made 1800 changes after that. Just trims and fine tunings — things that we saw that we could make better.

You mentioned that on this film, the Avid wasn't really used, but when was it that you felt like it was ready or did you have a project where you really loved the Avid and saw the value of it — non-linear editing, at least.Probably the next film. Steal Big, Steel Little. Perfect Murder was definitely cut on an Avid.

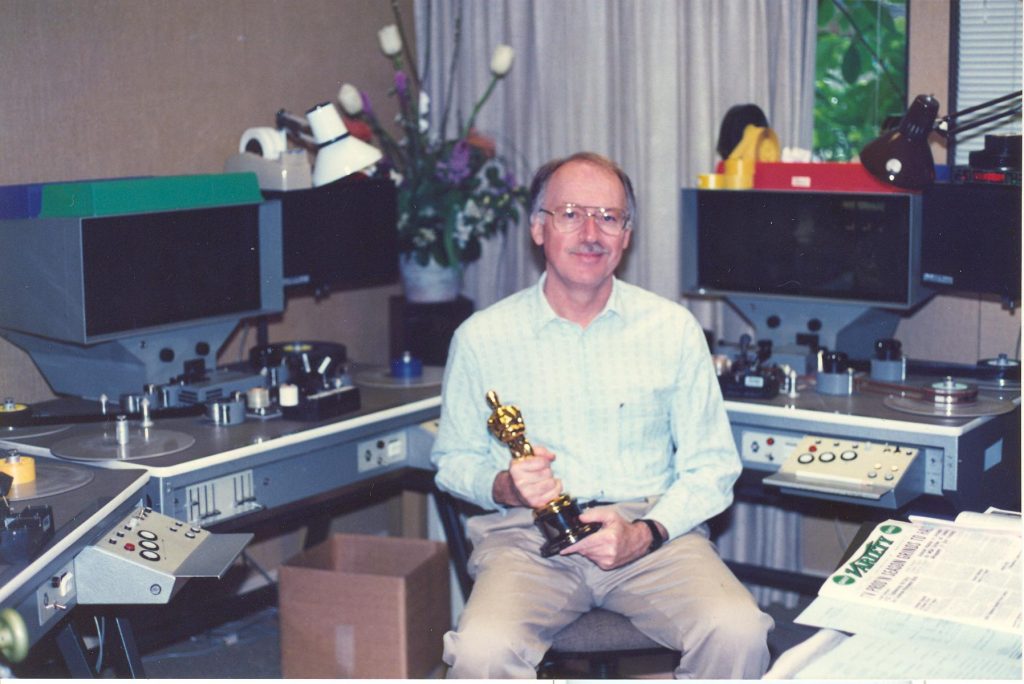

You know, Artie Schmidt just died.

Arthur Schmidt, ACE.

Yeah. Yesterday. I posted a little tribute...

Arthur Schmidt, ACE.

Yeah. Yesterday. I posted a little tribute...

You look at my editors on Chain Reaction, three top editors there. Artie lived in Santa Barbara. We used to see him all the time. Zemeckis lives here, too. Chicagoans in Santa Barbara.

Got any interesting post stories about The Fugitive you want to share?Frankie Montano — who was the sound effects mixer on Under Siege — was 27 years old. He sat next to Don Mitchell, was the top dialogue mixer in Hollywood and Don mentored him. He was nominated — the first time he worked with Don Mitchell — for an Academy Award. The next film he did was The Fugitive. He was nominated again. Cut to today, he's mixed 200 movies for Universal. They tore down a shooting stage and built a dubbing stage for him. He doesn't work for the sound department. He works for the head of the studio, Donna Langley. So he heard we were going to remaster The Fugitive and he called up, says, “Andy, you got to let me do it. This is my legacy. I don't want anybody messing it up.” He got Warner Brothers — he had friends over there — to send over the masters to Universal. That's where we remastered it. He’s playing it back and I say, “Frankie, something's wrong. It's all sounds looped.” It was so clean. And I wasn't used to hearing it that way. I said, “You got to put more of the street noise in there.”

So much of the movie is montage. So much of the movie is following Tommy, following Harrison, following the marshals. In the montage, you're cutting back and forth between the two forces, and that has to do with the non-linearity of it. One of the long-form making of The Fugitive documentaries that's on one of the Blu-rays, Don Brochu talks about how, Harrison goes in one way, and in the next cut, Tommy comes out the other way.

How do you feel about temp music as a director? Do you like to hear it in your cuts?

How do you feel about temp music as a director? Do you like to hear it in your cuts?

Oh, yeah. You gotta have it. That's the problem. That's what drives composers crazy. But the good thing was James Newton Howard did The Package. That's the first film I did with Tommy Lee Jones…

The editors were Billy Weber and Don Zimmerman.Yeah, two huge editors. Donny Zimmerman was recommended to me by Hal Ashby and he recommended James Newton Howard, too. Some of the score for The Package I had in my mind would work for The Fugitive. And if you listen to it, you'll hear that Copeland kind of big city sound. You’ve got to use temp music. It gives it life. You can't evaluate certain things if there's no music in it. And the problem is whether the rhythms of the music determine the cutting and then the composer’s forced to work with that.

Don Zimmerman — at the ACE Awards this year — received a lifetime achievement award. Two of his sons are editors now — Dan And Dean — and David is an assistant editor. Don looked great at the ACE Awards. Hiring an editor or finding new editors: what drives you to to choose an editor?

I guess seeing their work, seeing how it's put together. And then, of course, it has to do with compatibility. When I sit next to somebody for hours and hours at a time.

There are a couple of editors who work with me as assistants who became very big editors. Christopher Rouse. He was an assistant editor on Above the Law.

Wow. Yeah, he's an Oscar winner.Oh, yeah, and here's another one: Paul Rubel. And he worked on The Final Terror with me. And then the other one is Chris Wagner. Those are all people who were in cutting rooms with me as assistants.

I'm sure they learned a ton.Well, not necessarily from me, but from the editors they work with. How do you pick an editor? Based on their work and their reputation and their ability to quarterback a movie. We didn't used to have post-production supervisors.

So it's management.

Now with visual effects you’ve got to have all these people there that track everything. I've had several assistants who became visual effects assistants, then became editors through that. And the editors are off the picture and they're still previewing it and making changes. The assistant has all the responsibility: I want this version for Monday night. I want this one for Tuesday night. It's hard.

I was working on Medium Cool as an assistant cameraman: loading magazines on a phantom unit with Haskell Wexler for Haskell. Chicago is a great place to start in 1968. I couldn't have done that in L.A. or New York the same way. They were open and you could get attached to certain people. If you worked hard they wanted you to be around to help them do stuff. They trained you. It was a great place. Also, after the convention [the Democratic Convention of 1968] it was absolutely fucking crazy. It was dangerous and exciting.

Anyway, say hello to Del. We shared a lot of friends: Mike Gray and Jim Dennett ... and those were characters.

I will do that. Any last thoughts on the editing of The Fugitive?I'm just very grateful I had such a tremendous team to help put it together. Great contributions from everybody You know, we shot the Saint Patrick's Day parade. And then the musicians union said, “Well, you can't use that footage. It was under an AFM contract.” We brought a couple of bagpipes and put him between the stages and recorded that, but we wound up using the real footage. You couldn't beat that footage.

That's a great scene. Just the cutting of that back and forth between Harrison putting on hats and taking off coats and trying to blend in and Tommy Lee searching for him.It's amazing. You see Harrison walk off, it pans over and there's Tommy right behind him, missing him.