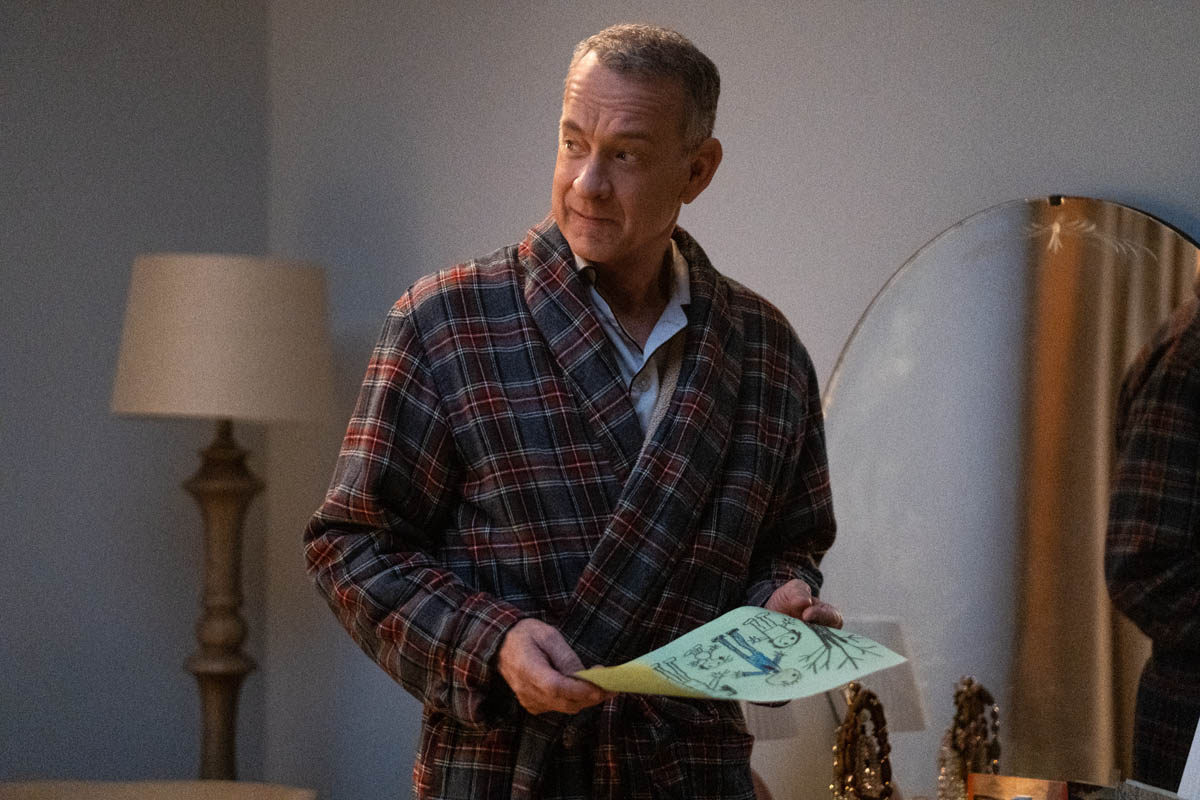

Today on Art of the Cut, Oscar-nominee Matt Chesse discusses the editing of A Man Called Otto.

Matt was nominated for an ACE Eddie and an Oscar for Finding Neverland. His other feature film credits include Christopher Robin, World War Z, Quantum of Solace, and Monster’s Ball.

This movie is based on a book. Did you read it and when did you read it?Oscar Nominee Matt Chesse discusses editing A Man Called Otto

CHESSÉ: I did read the book before we started filming. My wife usually gets to the source material before I do, because I usually find out something's coming up while I'm still working on the previous thing. Marc Forster (and the director of this film), who I worked with for many years, tends to run projects up against each other.

So I'll say, "Oh, I think we're gonna do this book, A Man Called Ove." and my wife will jump on it and read it just prior to me reading it. I read the book, then I watched the Swedish language film and then I read our screenplay just to be on the same evolutionary track as the material.

We've done book adaptations before, but this is the first time we've done a remake of a movie where I feel like we were in such conjunction with the team who made the original adaptation. Our producers were a Swedish company called SF Films. They did A Man Called Ove so I knew we were ‘backing into a garage’ where a lot of people very familiar with the source material were going to be.

I tend to try to do research when I know what I'm coming up on. I watched all the Bond films before we did Quantum of Solace. So I read the book as soon as I could and had the whole thing in my bloodstream before we started filming. Then you try to forget it. You try to store it all up and get all your moments and your feels and your beats and the things that you think are gonna be special either from the page or from the script or from the other film. You have all these sort of benchmark expectations that you want the movie to hit. Then you put those away and you dive in with the material that's coming at you and you discover a whole lot of other things that you weren't expecting. Then sometimes you try to guide the material back to what you thought it was gonna be. You try to build it 'cause you have an earlier version of it in your mind that you made up that you're going for. Or you let new things occur that had never happened before that are just intrinsic to this project. Between both those roots, I think you come to a happy place of getting the best of the material.

I've talked to editors who say, "I don't want that in my head." and others say, "Oh, of course I read every single thing I can get. I do as much research as I can."CHESSÉ: I think it's a personal thing. It's a subjective thing. It's whatever works for you. I personally don't like to go to the set. I like to visit set, but I don't like to be too close to the production because I feel like the world that we are given is bracketed off from the reality of the set, so what's going on just outside of frame is not really our business.

We're the “super audience.” We're the first responders to the material. I like to stay a little fresh to that because whatever struggles they have to get to the material in front of the camera, I don't really want to know about that because it allows me to be able to elevate the material without that toxicity leaching in.

Generally, the director will come in and say, "Oh my god, this plays so much better than I thought it was going to. This was a terrible day." Or, "That day player let me down, but he's playing great." If you remain outside of that, you don't know the day player wasn't happy on the day. Then you can play to its strength and give it the blind taste test and really take the stink off it, which I think is a big part of our job. In terms of absorbing the material or soaking in it, I think I - as a film fan and a literature fan and a pop culture fan - like to do the homework because I don't mind having influences get into my work. Generally, whatever it is that's influencing you or that you're shooting for will probably wind up getting disguised and folded in. But if it helps you get the signal and hone in on where it's gonna go, then it's fine, because nobody's gonna look at it and say, "Oh, he's copying this beat from 'Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.' They're just gonna feel like the scene works. It doesn't matter what's going on in the back of your mind that you're pulling it towards something. I like to immerse myself in that and be prepared, and it makes for stimulating conversations. The author of this book, Fredrik Backman, was a super engaging guy and really lovely to meet. I was really glad that I'd read another one of his books so that I had done my homework and I had things to talk to him about. That's part of the fun of the job - making connections with people.

If you've done your homework, then you have genuine passion about all the little tributaries that come off of the material that gets you. I'm a fan. I'm a fan of the homework and I like to be aspirational in shooting for targets in the editing room. I like to have a bar to set, to calibrate, to "embiggen" the material, to borrow a word from The Simpsons.

Tell me about your use of jump cuts and what do jump cuts do for you? What's the power or the value of them? Do you have to use them early to get the audience used to them, or could you do jump cuts at the end?

Tell me about your use of jump cuts and what do jump cuts do for you? What's the power or the value of them? Do you have to use them early to get the audience used to them, or could you do jump cuts at the end?

CHESSÉ: Sometimes jump cuts are a factor of compression. Trying to get things down to time. Sometimes they're suggestions from people who are giving you notes, "Why don't we just go from there to there?" Sometimes there are practical things.

I think it helps if you find a language - if you're gonna employ jump cuts, if you're gonna employ fade to blacks or dissolves between scenes, or if you're gonna do synaptic, brain-crackly associative editing - I think it's helpful to lay that pipe early and give people an idea of what the language in the movie is. If you start to employ them out of the blue in the fourth or fifth reel, it doesn't seem like your film. It's always good to do a little bit of gear-changing. I think jump cuts are helpful in keeping people on their toes and giving people a language. I think those are really helpful in being able to accelerate the story, accelerate the timeline. They're gonna become necessary at some point. So I think if you can give a little bit of modern, edgy editing and a little bit of crackle to it early on, it allows you to have more flourish as you're going because you can't just whip that stuff out later.

I think you could set up an audience in the beginning of the movie. You could show them how to watch the movie and what to expect and how things like flashbacks are gonna occur. Or if you're pushing it on somebody's face and that's gonna elicit a flashback or a time jump. If you open up with some of that stuff, you let people learn how it's gonna go. In this film particularly, I knew that this isn't about jump cuts, but I knew that we were gonna want to go a little slowly rhythmically in the opening because Otto's life is slow.

SPOILER ALERTThe time passing in his house, his memories, he's stalled a little bit in the beginning of the film. I knew that we weren't gonna wanna be rush-y pace-y cut-y. Marc and I both tried to establish a languid feeling in the house, so that when we came back to the environment where he was trying to commit suicide, where he had control over things and where it was his space, he'd been living with all of his memories, we could slow down and we could settle into that. So if he stepped outside with the neighbors and he's being provoked to come out and help them or engage with the outside world, we tried to stay off of the music whenever he came back and closed his door. We tried to stay in a reflective feeling that suited how the memories were coming to him.

END SPOILER ALERTI picked up on a vibe in the character that I felt he had auditory triggers - that things bugged him sonically that were the cacophony of the world. When we got inside where he was able to shut things out and be in control of his space, we tried to make that very calm in there, because that was how he would've wanted it.

The jump cuts I employed, or the more edgy editing was to represent the outside world and the pace that it goes at. I wanted people to be able to be patient enough to go slowly through his world if we wanted to go slowly through his world and not set a comic clip. You get a lot of notes about pacing and punching things up when you start sharing it with people. But I think we really wanted to hold down the opening of the film so that we could get under his skin and feel like an older gentleman who's spending time by himself. We didn't want to crank it up in the front end and pace it to that 'cause you can't stop that. You can't slow down to that.

My daughter's taking a film class right now and she was telling me they were gonna watch Breathless today. I was telling her that Breathless was really a place where we all learned about the Raging Bulls - that era of filmmakers really learned to throw continuity out the window and do jump cuts and just get to the next bit. Zap people into the next moment that was important to "get rid of the shoe leather," and I think it's very liberating. I think jump cuts are really helpful in not having to pay into the account of, "Yes, they've started dinner, but do we need to go through a montage of them preparing the whole meal? Or can we just cut to the plate coming in?"

Those things are very liberating and necessary to have in your pocket and sprinkle them throughout so people can keep up with the gear-changes that you sometimes have to make.

</p> One of the first times I noticed the pace pick up was the backing up of the U-Haul. All of a sudden, a much different pace of editing than the rest of what we'd seen up to that point.CHESSÉ: So I think that's two things. It's partly the conscious thought of wanting the outside world to be more alive, more engaged, more complicated, more frenetic than what he's trying to protect inside his house. So there was that in terms of inside world and outside world.

SPOILER ALERTThere's also a coverage thing. For example, the way that Mattias Koenigswieser - our DP - and Marc had shot the suicide prep that bookends the parking. They did it very economically in just a few setups. Very deliberate and very static. So I had to compose that in a certain way.

END SPOILER ALERTWe took it slow and we let it be kind of painterly and wide and locked off. Then the material that they shot on the day of the outside parking scene, there were so many more setups, so much more material to go from. So just from trying to cover the material and get the most out of it while having all three of those actors doing comedy bits, you wind up having to jack around and say, "Well that line's great from inside the car, although it makes no sense to be inside the car. But that's where this beat goes down the best between Tommy and Otto. So I'm gonna be on the front seat of the car and then I wanna show the taillight." Marc isn't generally a big fan of inserts or detail shots. He does more wide coverage and then I get to pick through it, but I can usually be anywhere 'cause he's got most of the things done in masters. So just by the amount of coverage that they did in the car scene I had a lot more cards in my deck to play with and a lot more places to cut to. There were two other POVs with Marisol and Tommy, it was not just Otto. You're setting up this initial relationship where Marisol and Otto share more in common than they think they do. They're both trying to micromanage Tommy's parking and they think they know the best way to do it. You hear Marisol saying, "Back, back, back," and Otto's hand is directing him as if he's the one who's talking. There was a lot of opportunity to overlay their commonality by cutting to Otto talking while seeing Marisol. Or hearing Marisol, seeing Otto, then cutting to Tommy and having Otto's signal jammed by both of them.

It's a slapstick thing, it's a relationship thing, it's a performance thing, and it's a ‘number-of-angles-offered’ thing. Parking and re-parking a car is not the most hilarious setup. So the more goofy, funny bits, reactions, eye rolls, detail, and punchiness you can have, it makes that scene saucier, funnier. You get more of the dynamic between everybody. Then Otto gets inside his house and shuts the door and you can exhale. Then he's back to his old pacing.

SPOILER ALERT

SPOILER ALERT

Some of it’s intentional, some of it's practical, some of it is what the scene needs. But I also think you feel that it's pacier because it comes right in between these two very quiet scenes. He's a little reluctant to commit suicide. He wants to do it; he wants the end goal. But approaching the noose and getting ready to do it, he's distracting himself. He's looking at books, looking at pictures on the mantel piece. There's a reluctance to it on either side of this other scene where he feels very forceful. He comes out of the house on a charge, he's giving directions, and he's the general of that block. It's like two different sides of him. It just worked out nicely. But that's why that scene feels pacier and I just think all the encounters with people are covered quite a bit more than the stuff of Tom by himself.

END SPOILER ALERTTom's so good that you don't need that much coverage when he's by himself. Then when you step outside and you have all these other people, there's a lot more engagement. The stuff of him alone interacting with the cat was almost partially covered because he nails it so quick. They're more economically shot, if that makes sense.

I had not thought of the really interesting idea of joining the characters by seeing Tom and hearing Marisol and the reverse. It starts to create their partnership early in the film.CHESSÉ: I have worked with Marc for a really long time and we do have a shorthand in terms of me going into the material and “his taste is my taste” at this point. He said something very small to me: "They recognize something in each other. They have an affinity, although it's a begrudging thing at first, but they're both slightly micromanaging and controlling and they're very functional people and Tommy is not." There are a few scenes in a row right there where that happens. When he mentioned that character thing to me, I just started looking for it. You can build those things in. If somebody gives you the right size comb to go through stuff, you can almost always find what they're looking for if they mention it, if they seed it beforehand.

When I was cutting the scenes on the doorstep, Marc said something else really small. The scene where they come over and introduce themselves and she gives him the food and he tries to shut the door and she puts her foot in the way. I cut it and showed it to him the next day, because he was concerned about some coverage and wanted to make sure an angle worked. So I bashed something together. His first look at my first version of that scene, I had really played a lot to Tommy because he was doing some funny stuff and he said, "I think you should try to stay with Otto looking at Marisol because Tommy is the sidebar. He's never seen anybody quite like this person before."

So I went back and honed it a lot, removed a lot of the interplay between Otto and Tommy, and just made him a distraction. But Otto's focus was very much on Marisol and looking at her like an animal in a zoo. As if he's saying, "I've never come across this species before." It really helped the scene when I played it back for him and he said, "Yeah, that's great." That's the way he directs me. It's sort of like Jedi mind tricks, very small. I think he works with the actors the same way; just small indicators and you pick up on it. He's a man of few words, but they're well-chosen and I pay attention. If he gives me that kind of instruction, I can easily pull it off. I went back in and made sure that was what was coming across. It unlocked a lot of really cool things 'cause I started looking at the scene slightly differently and watching her when you might have wanted to be on Otto or you might have wanted to be on Tommy.

It helps when you're in the cutting room and putting things together to have any kind of input, or goal or just a note like, "Come at it from this angle." You can become come quite overwhelmed with all of the options. When somebody gives you a pickaxe to go at things that have a certain size to it, it makes it easier to find the nuggets.

Sometimes the director will give you a note on one scene and that unlocks or informs a lot of other scenes the same way.CHESSÉ: I find notes fun and I find the challenge of trying to take another swing at things based on somebody's first impression of it - especially directors. I think it's really fun and really challenging to go back in and play up to what somebody else's notion of what it is. Marc is very generous in the space that he gives me to do my version. He's very subtle in the way that he wants it adjusted. I think it can really make things better to take him seriously and not push against them, but to really wade in with that sort of challenge. "Make it like this or make it more like that." Or sometimes he'll just say, "Make it colder, make it slower.” The littlest thing can set you off on the true essence of the scene.

Take the note as a creative challenge, not a complaint.CHESSÉ: Exactly. "Take the note as a creative challenge, not as a complaint," is a great piece of advice.

Tell me about how you dealt with flashbacks.

Tell me about how you dealt with flashbacks.

CHESSÉ: Flashbacks are like a transition and they're a staple between scenes. How do you get from reality to the flashback without losing people? I think there was a lot of discussion early on with some people reading the script being concerned about the flashbacks. Because Marc's intention was to mix things up and shoot it in such a way that we could sometimes have a flashback where Tom's son, Truman, was playing Otto and maybe have Sonya, the wife, in both places. Maybe she is in Otto's current living room or car. Then she's also in the restaurant where they're having their first date. What they gathered were more options. It wasn't really decided on, there were more places to synaptically go between the past and the present and Otto's participation in it.

As we tried to cut the things together, we realized that it felt strange to have Tom in the scene with Sonya because she wasn't aging and her timeline really belonged with Young Otto. To have him interrupt that wholesale in the same frame felt weird. But it was really good for the flashbacks to have him murmuring some of the dialogue or providing some of the lines that Truman was gonna speak and to participate in the flashbacks from the here and now. I had a lot of options. I had a lot of ability to slip things around 'till it felt right. I knew from reading the script initially that there were a lot of flashbacks, which can be challenging. Depending on the way that they're covered and the way that they're supplied to you, they can be more successful or unsuccessful to a lesser or greater degree. I was up for this and I was paying attention, but I think that they really did a good job on set supplying me with the grease to lube these things up.

In the first one, which is an important one because it lets you know these flashbacks are gonna be happening, there is a shot of Tom sitting in the chair and he's flipped through the book and it's a slow close-up on him. We hear them come into the room and put down the boxes and they're discussing the bookshelf that he's gonna build her 'cause she's got so many books.

When I watched those dailies, Marc had the other actors entering the room and doing their actions at the other end of the set. Tom was just watching them and I heard their vocals in production. I heard them across the room enter, and it just felt like the flashback was already going on. I didn't have to do anything. He was having the flashback and you were watching him have the flashback. The actors were in there moving the stuff around at a distance and they felt sort of ghostly the way they were picking up on the mic. I said, "Well, this is the first beat of the flashback."

Truman asks, "Well, how many more books do you have?" And she says, "Five more boxes," and then Toms mutters to himself, "I'll just build you another bookshelf." Then you hear Truman echo him in the background. It's as if he's been through this memory many times. He's played this memory back to himself and it's a sweet spot. It's a pleasant place, he likes to replay it, and he knows his part. So he says his line, which triggers Truman's line. I know exactly what's happening by watching Tom and hearing those voices, I don't even need to cut away.

So I stayed with that old rule about don't cut 'till you need to. I didn't need to cut for a while and then we purposefully kept young Otto played by Truman Hanks out of that scene. We see his figure reflected in the TV, but I only cut to the closeup of Sonya 'cause I wasn't ready to break Otto out of that scene yet. So I just stayed on her and Tom, left Truman as a voice and a shape in the background, and kind of bonded Tom with Sonya. Then in the next flashback, he goes to bed, he drifts off in his sleep, and that's the first time we cut to Truman.

We see him lying in bed asleep, then we see Tom's hand reach for Rachel Keller's hand, and then we cut to Truman's face in bed where Tom used to be. We cut back to their hands and it's Truman's hand holding Rachel's hand. We're introducing the audience to Young Otto as an avatar for old Otto by doing a sleight of hand. That's him in bed and that's clearly his wife's hand. So if he's holding her hand, then this is what he looks like in the past because he's gone back in time.

Then we see their young hands together. Now we're in the past, then I cut to the reflection in the picture frame, and we see him lying in bed alone. We're reminded that he's drifted off. It's sort of a dance of turning over these cards one at a time to take the audience by the hand and introduce them to these players show them how this reverie is drifting over him. Then he wakes up slightly and you realize it's bittersweet. You realize he's alone and he was grasping for her hand, but it's not there. Then he looks back out the window. I asked my assistant, "Can we take what's outside the window and replace it with something? Is that possible?" There were a couple of setups where I think the light had changed from when they started at dawn and then the sun came up and it started coming in the window. In the later takes, they had put a green screen up outside his bedroom window. What can we put in there? We experimented around with the train moving and we played around with that window as a transition device for the flashback.

When we got around to the mix stage, I cut from the view outside his window, which has changed from his bed to the window. We see that what's outside the window is different now, and then the next shot is an x-ray up to his heart at the army base where he's getting his physical and he gets rejected. The window is very reminiscent of the window from the bedroom. My sound designer put some army vocals outside the window.

The first time we're in the bedroom and he looks out the window, we hear trash cans and there's morning street sounds. Then the next time it sounds like the army. We cut to the window in the army barracks. We've changed locations and he's holding up the x-ray.

Part of it was happenstance and part of it was intentional. They definitely framed the windows at the army barracks for him to hold the x-ray up against as a similar feel to the windows in his bedroom. But the fact that Brad Besser, my visual effects editor, and I had worked up this gag where we could do what we wanted outside the window. We added another level to it, then we put some sound on it, and it became this really fluid dreamy, echo-y drifty thing that really took the sting out of anybody being dislocated by the flashback kicking in.

Director Marc Forster and Tom Hanks

Director Marc Forster and Tom Hanks

Like most things in good editing, there are plans, there's inspiration and happy accidents, and then there's the contribution of a really tasteful creative ally who's working with you. The whole thing just comes together. There have been some reservations about getting lost in the flashbacks and trying some of the things Marc wanted with double casting Tom and Truman both in the same flashback. I think we were all on point to make sure that stuff was very smooth and didn't bump but slightly magical and graceful. Because of that intention, because somebody raised their hand early on and said, "I don't get. I don't get what we're doing here," we made sure that you would. There's only one flashback that is the result of taking something out. There's a scene where he's kicking people out of his house and rejecting the idea of taking the cat on. He shuts the door, he turns around, and he’s drawn into a flashback about when he proposed.

Initially that was something else, but we lost a scene for length and had to make up a transition triggered by the coats and the memory of Sonya. So I had to look at my other transitions and look at my other flashbacks and ask, " Now that we've got this ripple and we've taken the scene out, what can I do that feels intentional, that it keeps up this quality of standard flashbacks? We borrowed a line from later in the scene and put it across the coats so that the coats were being associated with Sonya. Once you get in the groove of it, then you have to make sure that they're all equally tasty. That was the only one we had to do on the fly and I think it works. It sticks out to me a little bit 'cause it's not quite as graceful as the more plotted ones. It was a result of some editing and some rippling of scenes.

I worked on a Nicholas Sparks movie, so there was a lot of double casting of a couple when they were young and fell in love and when they meet in later life. When we showed the movie to people, they asked, "Why are there two characters named Dawson in this movie?" That's Dawson. There's only one. That's him in the past. They almost thought there were parallel timelines. As if the movie had a stroke and there were two timelines with the unintentional multiverse. You know you're in trouble when somebody asks you, "Why are there two characters named Otto in the same film?" No, no, no. There's only one Otto. The way that scene plays out with the handoff from Tom to Truman stepping nimbly through it, it's elegant and I hope emotionally impactful. But it's also a provocation and a handhold for the audience of "I'm gonna walk you through this, and by the time we get into the flashback, you are gonna understand exactly who that was." Which is why - after I'd introduced Truman and swapped their hands out for young Otto's hand and young Sonya's hand on the bed - I went back to the window, back to the reflection on the wall in the glass to show that Otto is still lying in bed alone to take you back to the original. It's spoon-feeding them so people don't get lost.

It's setting up a language for going into other flashbacks. It's satisfying the producer's anxiousness about people getting lost and hopefully doing all that with grace so that it feels. Un-clunky for those who are getting it. There's nothing worse than covering a note or covering a suspicion, a hunch that people aren't gonna follow. Then other people who did get it right away say, "Yeah, obviously I knew where I was." There're a couple of cuts in Gangs of New York that I always bring up with my editing students when I'm talking, where they meet in the middle of the movie for this big brawl in the street. They got sticks and torches and they're gonna go at it.

When guys show up in the street, it cuts to mirrored shots of them from earlier in the movie. If you're paying attention, you're asking, "Why are you doing that? I didn't need to have that flash frame in there to remind me. I'm watching." I think that's what you wanna avoid something that feels uncalled for or that really sticks out 'cause you walk a line with wanting to keep everybody on board but not wanting to insult anybody or oversimplify things. I think Marc and I experimented along the way as filmmakers with simplifying or oversimplifying or remaining willfully obtuse and not explaining things. There's benefits and deficits to both those things. It's not always great to leave people in the dark or leave them guessing or assume that they get things.

As we've gotten more mature as filmmakers, I think we've become a little more sensitive to doing all those things gracefully and not assuming that everybody gets it or that people like to be left in the dark.

Let's talk about reaction shots and when not to be on the speaker. How are you deciding what to play on Otto and what to play on Marisol? How do you make the right choice? Specifically, I’m talking about the scene in the Swedish bakery after Marisol parallel-parks.CHESSÉ: I remember on Finding Neverland, Richard Gladstein - our producer - who was a Miramax/First Wave guy, had done Cider House Rules and a lot of great films. He was our Miramax minder. He was our creative producer who was like very much in the dugout with us and was more seasoned than Marc and I at that point. I was particularly interested in his feedback because it is interesting to get different perspectives from different agendas and different experiences. I remember him saying to me during a dinner scene with the little kids and Johnny Depp, " You know, you don't always have to be, 'I'm on the person that's talking,'" because I was being very back-and-forth. But it hadn't really occurred to me at that point - 'cause I hadn't done that many films - that maybe I did wanna lean into some reactions a little bit more. I experimented on that movie with savoring that, looking for places to let something soak in just riding a reaction shot or not doing what's expected. It's a delicate balance of being in the sweet spot of what the scene needs and what's satisfying your audience. Ostensibly, I'd say that's Otto's scene because it's Otto's memories.

It's the warmest that he's been and the most explosive to her. It's almost like he's gone there for some confessional. He really sets it up. He takes her to a place that's very personal to him and he is ready to chat and watching that stuff come out of him was the most beckoning thing when I was going through the dailies and watching Tom do that naturally because he's defrosting in a way right in front of us. That's the most his guard is down in almost the whole movie, because his walls go back up by the end of the scene. It's two o'clock and he blocks her out again 'cause she oversteps. I gotta say, it's not hard to know when you wanna cut to Marisol because she's so well suited, it just fit her like a glove.

She's listening to Tom as we're listening to Tom. To go through her dailies - seeing the kindness, the empathy, and the engagement. She's prodding him and giving him just enough, she doesn’t want to spook the horse. Marisol is giving Otto just enough to keep him going without letting him realize that he's really sharing himself.

She's very gentle. I go through all the dailies on one character and I try to figure out where and when I wanna be based on that. Then I look at the other character, I'm thinking, "Oh gosh, there's a stack up here. I want to be in both places, but I can't do a split screen." But I find all of her warmest stuff. I think when you are done collecting the Otto dialogue and the Otto delivery, and you go back to Marisol, you see her listening to a line that you would've assumed you'd wanna be on him for. But you see her taking it in a way that's exactly how you wanna feel when you're looking at him saying the line.

I would just as well be served by being on her taking it as being on him deliverying it. Either it's a performance thing or a script thing. Something might be a little too sweet if you let the actor say it. Whereas if you let somebody else absorb the line, rather than the actors say the line, it might make something feel a little more natural and less expositional. It's like you're eavesdropping. You're watching it with two minds. Am I the speaker or am I the observer? Sometimes it's a great tool if you've got a take where you're thinking, "I really like his delivery up to this point, and then I really love his delivery from this other take. But if I go to her and let him speak the line over her, I get the best of both worlds. I'm watching her warm absorption of it, but I'm also getting his best read without having to feel like I cut away from that take at a weird time. Again, it's prestidigitation and it's kind of a dance. It's like you're making soup and you're testing it. A little salty, a little sweet, a little sour, and you're sifting those things. She's almost a silent partner in that scene, but she's so giving and she's so great. When I watched her dailies, I thought, "Well, that's what I would wanna be getting back from somebody if I was talking to them. That would make me want to keep going." I feel like she's just a green light. It's a pretty organic thing for me.

I'm a people-person and I like to watch, I like to listen, and I like to talk. I'm having the ultimate cafe experience right there. Being able to make it go as well as it can, because I'm just really fond of both those performances. That made it pretty easy.

It really sounds like you were choosing the actual moment of Marisol listening to a specific line. Sometimes I’ve had to fake the reaction with a moment reacting to another part of the script.

It really sounds like you were choosing the actual moment of Marisol listening to a specific line. Sometimes I’ve had to fake the reaction with a moment reacting to another part of the script.

CHESSÉ: With these particular actors, it was a real smorgasbord. They were both so in it the whole time. I think the two of them really locked in.

It was really just a response thing of going through a smorgasbord and picking all the things that feel appealing and going back for the things that you wanna double up on. Nobody else is ever gonna go in and watch this stuff uncut after I go in there. Probably not even the director. It's probably the one time somebody's gonna sit through eight or ten takes of Mariana Treviño listening to Tom lay down this scene. I'm watching it sort of drift by me.

But when it lines up where he's saying a line and she's absorbing it, it's a combo of what I'm hearing and what I'm seeing and when it tugs a little bit or breaks a little bit or feels like really organic. For example, "That only happened in that one take. She turned her head or she bit her lip, or there's just something very fond or whatever the emotion you're going through." But in that particular scene when things lined up, you just feel it. You hear it, you see it, and you say, "Oh, that was in sync. I don't even need to borrow Tom's line read from another take. I just want to be right here because all the stars aligned in a certain way. That's a movie moment. That's a keeper.

There's a scene where Otto wakes up in the hospital, he's had a heart attack, and Marisol is at his bedside. There was just one take where they were in a medium and he had just woken up. She held his hand and there was just this fondness there that wasn't in any other take. I didn't even need to be right there at that moment. I could have been on either one of their closeups or I could have been wide or on the other side of the bed. But when that stuff goes by and you know that it's not necessary and you should scoop it out. But that's gotta be in there, that was real. That really touched me and moved me. I think more than anything else, that's what I am guided by when I'm editing. Trying to shepherd all of the most poignant moments or all of the most real-feeling moments. Sometimes it's an angle, or it's the lineup, or it's the body language, or which take it occurs on. But that beat goes by in that take and you say, "Ah, I gotta use that." and it speaks to you. Especially the moments that feel like one-offs, like when an actor says something in a way that is real to life, but is unexpected. Or that was an interesting read and she only said it that way once and that felt really off the cuff. If I put those in and protect all those beats, then it just makes everything else feel more real, because that had to be real.

That was just so organic. I think it really helps the material if you watch for all that stuff. The one-off stuff and the moment when they're right there, that is not gonna occur again. Nobody's gonna go back for that. It's not mentioned in a script, it's not a beat or a moment that is outlined, but you catch it and you say, "Oh my God, that was amazing, I gotta protect that." That is probably what drives me in the first cut going through the dailies - collecting all that stardust.

It's an honor and you're charged with that. You're the only one who's gonna go down to that mine again and pull that stuff up. You're custodial duty and you're charged with this to deliver that stuff, to bring back the gold. If not, put it all on screen and know where it is so you can file it away. Bring it back if you need to make things warm or colder.

I worked on a film where they decided that the female character had been cut too coldly in the beginning of the movie, although she was supposed to be cold and that she had “resting bitch face.” I had to go back through the movie and warm her up and make sure that in this certain section she wasn't coming off too 2D. Although I really think the actress would've been fine with how I had cut her, the two female producers I was working with said she's not likable enough. Sometimes your instinct is not as box-office-friendly, and you're going for truth.

Did your choice of performance change when you saw the entire film in context? The best performance is not necessarily the best performance that makes a smooth arc.

Did your choice of performance change when you saw the entire film in context? The best performance is not necessarily the best performance that makes a smooth arc.

CHESSÉ: There's always a day of reckoning when you put things all together and you watch 'em on a run both in performance and also in length and breadth of scenes. Sometimes if you cut your dailies every day, you make everything a meal and then you put it all together and you're thinking, "Oh, this is actually tapas or this was just the salad. Or this was an appetizer, I didn't need to make a meal out of this. Or maybe this whole thing should just be a montage rather than a main course." Because a lot of times the coverage and the shooting on the day doesn't necessarily belie what the scene needs to be.

You can wind up with a lot more material than the movie really wants in the end. Just because they're at a remote location, they're not gonna be able to do another company move that day. Why not shoot it out? So they just wind up spending the whole day on one scene and in the end it could just be a couple of cuts, but you've got this kind of embarrassment of riches. I think a lot of those notions of looking in the thing as a whole happened on a lot of levels when you put the whole thing together. As Marc and I have progressed in our relationship and our collaboration, I used to wait and try to cut everything linearly as much as I could. I would go through the material as we got it every day, but I started cutting the movie at the beginning of the movie and worked towards the end and didn't worry that I had an assembly when he wrapped.

We just used to not work that way. We used to just go to let the thing accrue and Marc would be patient enough to let me cut linearly. Which I thought was a great way to go, because then the movie really tells you what it wants in each scene and it's much clearer than Frankenstein-ing together with all these scenes and realizing that you never get a three hour cut that you scratch your head at how to tighten it if you're cutting linearly, the end of the movie comes right when you want to get to the end of the movie 'cause you're laying out paving stones. Now, the calendars have gotten tighter and the expectations with turnaround and needing to share with the studio. We do much more of an assembly that's ready when he gets done with the shoot.

I have a little bit of a jump on taking out those rough edges and compressing things and modulating performances. In the last couple of films, we've had moments where Marc wanted to see as much of the movie as he could before he finished filming so that he could figure out when and where flashbacks occur. Marc wanted me to assemble the whole thing, record an actress reading lines, and place them as they were supposed to be placed in the movie, creating placeholders and audio for beats. There would be no need for reshoots. By reverse engineering the movie and realizing in an assembly form with another actor reading dialogue, I mocked up all of her scenes. It really worked like a glove, we nailed it. In terms of stepping back and modulating a performance or looking at the whole thing and needing to dial things in the wider sense, I would say in this movie, because Tom is so good, he was doing a lot of that bracketing and notching of Otto warming up for us.

He knew where Otto was at. No matter where we were in the shoot, no matter what day we were on, whether he was shooting on the porch, on the practical street, or whether he was shooting on the interior, on a stage. He knew what he had just done in the previous scene in terms of screen time, and he knew where Otto was at. A lot of that guesswork is gone because Tom's done the adjusting.

I'd say if he had a tendency to do anything that I needed to work with, he has a natural ability to be very charming and very sweet and very warm. I had to hold onto the grumpy as long as I could because sometimes, I personally don't think that he could ever be too grumpy for too long in this movie. Another one of those things that get in your ear when the author Fredrik Backman visited the set in Pittsburgh, he told Marc it's such a beautiful story. To watch Otto go through this transition, come to life, and go through this arc, Fredrik said, "Otto never changes. Everybody else changes. Otto's the same through the whole movie. He's always that guy. He doesn't get any warmer, and he doesn't get any colder. He's just Otto.” Marc told me that Fredrik Backman had said that, and I took that to heart. I'm not gonna let him get too warm and fuzzy, or I don't think Marc ever planned for him to have one moment of an epiphany.

It was more just like let him be Otto and let us discover who he is, but he knows who he is. I held onto that taciturn nature as much as I could and fought against Tom Hanks' natural charm to hold off and keep Otto 'cause I think a lot of the reaction of the movie has been people being able to accept or not accept Tom Hanks in a role where he's suicidal and grumpy. But I think that's why he wanted to do it. I think that was one of the discoveries of the movie is to see him withhold, and to see him not try to charm us and to see him not give a shit what anybody thinks and about this character. It's fun to do that bracketing, but I did have to keep an eye on holding him in place and letting Otto be Otto as long as I could. I think that we had, by the time we showed it, by the time we were done with what you would call the director's cut, we had worked all that out.

When did you start bolting scenes together on this movie?CHESSÉ: I love to get things flowing. It really helps with adding music and spotting the movie.

I'm a very presentational person. I like to spend a lot of time fine cutting and making things right. I don't really do a rough cut or an assembly and just say, "Well, it's gonna be something like this." I really like to take the time before I show it to Marc. I want everything to be in place and take as much of the guesswork out of it as possible.

Marc's the same way before he presents our cut. He really likes to get all the green screen out and basically wants to have no caveats. He wants the movie to just sing its song and say, "I don't have any problems with this. This is my version. I don't need another month." Then we'll begin the process of letting everybody taking a swing at it. But when I'm getting it ready for him, I'm very much fine cutting the whole time. So I will build reels that are empty of scenes that just have card-holders that say what goes where. I'll just start adding the scenes in as I get them cut, and eventually I'll have three or four scenes in a row that are shaking hands with each other.

I start stapling 'em together as soon as I can. I build ghost reels, I just drop the scenes in to the ghost reels, and they hang there until they meet the scene before and after. It helps me for bookkeeping and remembering where everything goes. But it's also just a way to get to an assembly quicker. 'Cause I find if I keep everything in bins for too long, I go back to it and I forget which version is the one I want. I'll lose my way. So when I feel like a scene's as good as I can get it, and I've banged on it as much as I can, I'll put it into this ghost reel, which eventually just evolves into being a full reel. I love watching movies and so I try to watch my movie as soon as I can. That's the whole joy of the job is that you get the first peek. I'm putting music on it and I'm getting my assistants to get the green screen out and give it back to me. I'm getting my sound guys to do sound along the way, and I'm putting it in. I hold back on score, but otherwise I'm trying to pimp it as much as I can along the way.

How do you approach a blank timeline? Are you a selects reel guy? Do you cut out of the bins?

How do you approach a blank timeline? Are you a selects reel guy? Do you cut out of the bins?

CHESSÉ: I want to draw some blood. I feel like it's really hard for me to start sniping and sub clipping from the first time I watched the dailies. I'm afraid that I'm gonna forget where I liked something. I wish that we were still in the practice of screening dailies with the director and letting the whole clip play in a room full of people at the end of the day and just feeling a room watch a scene, and letting it go on as long as it can in its pure form.

I find that when I'm alone I get pretty snippy and I start sub-clipping. I'm definitely a highlights reel guy. I have my assistants cut “dialogue strings” per line. I'll have them do that in the background as I go 'cause I find it's really helpful to have that as a reference when you get stuck for time or when you get notes and you need to change things or if a line's bugging you. If you just have 'em all laid up, you can just listen to everything - every line in a row. I generally pull sub-clips and then I just write something very self-referential to myself like “a great smile” or “very natural” or “he blinks” or just something very obtuse that anybody else who goes into my bin would ask, "What's with these comments? I don't understand." But it's like a filing system, and I will remember what my knee jerk thing why I sub clipped that. I have a kind of a crazy bin full of little bits that I like. To keep myself from getting into that blank timeline feeling, I generally will start two sequences of the same scene at the same time. So that I don't get stuck on the perfect one.

If I come to a crossroads, like I could go this way, or it could go that way. If I can't decide, I'll just make up another sequence and start it going in another direction. I feel like there's a painful thing about decision-making. You feel like you're drowning kittens. To let something go I'll have an A sequence and a B sequence, then I'll remind myself after I'm done with the A sequence, I'll go back and look at the B sequence and see if there's anything that I wanna graft onto it.

I often revisit my bins along the way of stuff that I've pulled to make sure that I didn't forget to go back to something great. Especially in a movie like this with Tom Hanks and these performances, there's so many great reads and you can't get it all in. But I try to keep challenging myself and going back and revisiting things.

One thing I do to keep the flow going in the beginning when I have an empty timeline: I play score under my dailies so that I'll put music on something that's the right tone for the scene or what potentially might be the music that I might put on there. I'll just play it on a loop. Usually just one piece that I like and it makes everything feel like part of a piece. It makes everything feel like it's already in a movie. It's sort of like a car, a magic carpet that kind of keeps everything moving for me and it makes it all feel, no matter how many dailies or angles or setups, if I've got the same piece of music playing underneath the whole time, it makes them feel more cohesive and it puts me in a little bit of an intake trance. It makes it feel like you're movie watching. I do that to keep the blank page thing from haunting or intimidating me. I pretend it's already a movie that's playing as I'm getting started.

Are you actually building your scene sequence from the sub-clips?

Are you actually building your scene sequence from the sub-clips?

CHESSÉ: I don't cut with the sub clips. I just use 'em as a marker to get back to the daily. I go back and watch the stuff that I've pulled. If I like it, I just match frame to the beginning of that clip and cut it in from the daily so that I'm not using sub-clips because they'll lock you out of stuff. I just use 'em as placeholders. I've found that when I made long strings of that stuff, it can be hard to separate out the stuff that you wanna use if they're all connected and you're watching the scene. It can become distracting or hard to choose.

I've decided to keep 'em separated now instead of putting 'em all in a big timeline and watching 'em because I would get lost in it. It was like an ocean of great options and I would have a hard time selecting. So I try to isolate them by making sub-clips and just having sort of a trigger phrase in the comments. I'm very into comments and notes. I have both comments and notes going in my bins so I can sort of talk to myself. I do cut clips in text view. Visually, I know what it is. I'm having a dialogue with my first impression of something as I'm going through it and saving things.

If you start cutting right away - if you start pulling sub-clips and noting things and breaking things down - it gets you into a pattern where you really do go through all the dailies and you really do savor everything and pull everything off to the side. It can be exhausting to turn around and look at the bin you've created and be see a mountain of stuff. But I also use color. I color the clips, like green or yellow or red if I'm really for something and it's just a way of winnowing it down. I'm pretty meticulous about performance and the best read. I try to rate that stuff and as I come across it, I try to highlight it and put it to the side and say to myself, "I've gotta put this in. I've gotta use this. This has to be seen."

I think that when they do those Borat movies, they do an A joke, B joke, C joke thing. Then at some point they just say, "All the C jokes have to go." It's sort of like that. I try to go an A read, a B read, a C read. Or vibes, maybe it's happier, sadder, or tougher, or crueler or whatever. I'll note those so I could keep them apart. You see one beat go by, you see one reaction and you say, "Oh, I really like that." Then every time you come to that reaction in another take, you're asking, "Is that as good as the one I had before?" So it's winnowing down, but my whole goal is just to always be at the right place at the right time with the best read. I'm feeding everything into the wood-chipper and then just trying to collect all the gold.

Once I lock in on a take or a run of performance or a place I wanna be, I leave those sub-clips behind. They're like bookmarks. I've tried to use the locators, but I just find they just slow me down. It's almost like a deck of cards, and I'd rather fan everything out and see jack, king, queen, ace. I see all the colors that I have to paint with.

When you are looking at other editors’ work, how do you judge them for awards consideration? What are you looking at that draws your eye and makes you say, "Oh, that guy gets the Oscar nod."

When you are looking at other editors’ work, how do you judge them for awards consideration? What are you looking at that draws your eye and makes you say, "Oh, that guy gets the Oscar nod."

CHESSÉ: I think the more that I can get lost in a movie is a good sign. You tend to watch things critically as an editor and ask yourself would I have done that? Would I have not done that? Or think that was an interesting choice, or I wonder what else they had to work with? You could be pretty picky, pretty critical, and pretty editorial in the way that you're watching the movie. I find it's when I can forget about the filmmaking process and the fact that I participated in it and just take the ride on the film. With modern editing and modern films, I tend to love when naturalism is done well.

When I watched The Lost Daughter, I loved the rhythm of it. I loved the time slip of it, and I loved the way that it handled that style, which doesn't always work for me. But it's a very modern thing where things are drifting in and out and you're hearing a little bit of this scene and that scene. You've got two different actresses playing the same person at two different times. This scene in the present is influencing this scene in the past. I could get really bugged by that not being done well. But when it's done really well, I'm envious of it. This is really organic and feels very called-for. I know it's not easy to have a director say, "I want this to just flow and just be loose in time and we're going back and forth." Affonso Gonçalves edited that film, and I just remember watching it and really buying it and really getting lost in it. Although it was a lot of editing, it felt very organic and very colorful. So when I realized I wasn't noticing the editing that I would normally be noticing, I think that's a good thing.

I look for things that I admire or think, "Wow. That must have been tricky." I remember seeing Memento and thinking, "Wow, I can't imagine having to cut Memento," and I really wanted Dody Dorn to win the Oscar. Because I just thought that was mind-bending.

A perfect example from this year when you watch it: Everything Everywhere All at Once. I mean, come on. That just kicked ass on all levels. The editing had to be so challenging, the timeline, just the wackiness and the slapstick, the action, and the character. Yet it had so much soul and had so much to say about parenting, about love, and about letting people go. I just thought it was such a profound movie, but it was wrapped up in these hotdog fingers.

I think I put myself in the seat of the editor a lot when I'm watching somebody with that many plates spinning and they're pulling it off and I'm sucked in. I can take myself out and say, "This is a great job. I don't know if I could have done this." That's always a good indicator to me when I break a sweat and I don't know what I would've done with this. Or at what point did they decide that this was working? Conversely, I look at movies that don't have things going on in them. I work hard to make a movie flow, coherent, and absorbable by as many people as possible. Then I watch a movie that just lays there and is not evolving or doesn't really have a point of view. I get mad at not the laziness, but the willful artiness of something that will take me out of wanting to vote for a movie.

I'm tough on movies 'cause I know how tough it is for me to get through the whole process of getting the movie across the line. I won't mention any names, but there was a huge movie last year done by a very high-profile director. But I just thought it was really meandering and I thought, "Why did this get a pass?" Some of those things do creep into it when you're judging. I think about the whole process of filmmaking and the success or failure of a movie to feel like something that I would've been in charge of, or what rigor it was put through.

Director Marc Forster with Tom Hanks

Director Marc Forster with Tom Hanks

CHESSÉ: I do bring most of my own jobs, but the value of an agent is having a bad cop who will ask for things and push for things that I myself would be reluctant to. I'm kind of a cheerleader, people-pleaser kind of a person, and I just want people to like me. But my agent is not afraid to say, "That's not good enough. He needs this." She can make me high maintenance remotely. I can get things served up to me. I've been with this same agent, my whole career. She really staked me when I was just coming into the business at Sundance. We connected through a friend and and she staked me for my first couple of films without charging me a fee. She waited to sign me until she was able to make me a deal that would bring enough revenue that I wouldn't notice that I was paying her 10%. I thought that was a really kind thing to do. I never get off the phone with her without laughing. She's just great.

There are spaces in between jobs where they find you fix-it jobs. They keep their ear to the ground. I can't be sure that Marc is gonna go on to the next thing he thinks he's gonna go on to and that he's definitely gonna take me along. So she keeps me in the game. She keeps my name out there, she helps me meet people. There are certainly four or five spots in my filmography where I've got stuff that she scared up for me that weren't Marc things. So I just think you gotta have somebody. It's like having a tax person. You just gotta have somebody else in there who's learned, who's tracking you besides your partner. Who's gonna keep an eye on things and is gonna be there for you. I've been on remote locations, called her upset wanting to get out of there, wanting to pull the plug and had her talk me off a ledge.

I think it's a necessary evil that's not even really an evil. It's the way that the system is constructed. If you wanna play ball, you gotta have one. So hopefully you have one that's looking out for you who understands your taste, understands what you do or don't wanna do, and can give you good advice. But I think it's a required thing that will get you the best deal and who's there as a panic button. I think there's a myriad of benefits for me in the end. I don't resent my agent!

Talk to me about the role of ego in the editing room and for an editor.

Talk to me about the role of ego in the editing room and for an editor.

CHESSÉ: Ego is fairly inappropriate as an editor. At least for me, I used to get in a snit when I was challenged or there were notes that second-guessed me, or felt like they were undermining what I was going for or like they didn't understand when I was a younger editor. I think it's very easy to be very dramatic and high-handed about that stuff. But as I've gone through the process enough times, my motto is “keep the drama on the screen.” I think you have to stick up for yourself and you have to defend ideas.

But I think the best person to defend yourself to is the director, at least the way my relationship works with Marc. If you're getting notes from outside, if you're being challenged, if you hear something as an indicator of the way things are going, or if you see a trend going on that you don't agree with, I think the person to express that to is the director. Empower them to defend you either playing it as their own card or just sticking up for the movie in general is to let them go into the fight. I don't think it empowers an editor to come off as scrappy or headstrong or making a big noise.

I don't do ego or alpha dog sort of stuff. That's not really my personality and you can't really fake it. I know there are some people who intimidate. They have reputations and they intimidate and they throw chairs or there are legends of tough-ass editors who are hard to work with. I can't really imagine that. I feel like our role is to be a consigliere and to buffer those things. I think ego and politics wise, the trickiest thing is to build a bridge between the director and the studio and the producers and studio heads and remind the director that there's value in notes and to try to ease some of those creative tensions and not to bring them on yourself. There's enough ego and enough push me/pull you going on. I think that if we add to that and get our back up as editors, it blocks the process.

I've unlocked some real keeper stuff by taking a note as a challenge rather than criticism. I also know that if you try to do notes badly, just to serve them up badly, to get people to get off of a note that you don't agree with, you can get stuck with it and they can really love it and say, "Perfect! Exactly," and you say, "No, no, no, actually, if you're gonna like that, I can do it better." So I really try to give notes my all and sometimes you surprise yourself.

Sometimes a note will come along that you didn't see coming or that seems off tone and you can really turn it into something. You can rant to your assistants, you can use your cutting room as a sounding board to blow off all your steam. I certainly do a lot. I download about what's in my head or what's in my heart, but I keep it at work. I try to keep it in the cutting room and don't let it spill over into the director's head because I feel like they have so much going on.

But then again, you have to pick your battles and you have to stick up for the things. Save your ego for the things that are really important, that are gonna hurt the movie if you don't raise your hand, if you don't stick up for them. I try to play the cards that are best for the film rather than myself. That's what's important. The film is more important than we are as individuals. So if you really know that something's best for the film, you have to find the sympathetic ears and explain to them why you put something in there or why adding this piece of music here or taking this piece of music out is not what's best for the film.

I find as it goes along, most of the things that you feel intrinsically as the editor wind up coming out on your side in the wash anyway. When they test and when they compare, you usually don't have to fight as hard as you think you do. You’ll find out what's the best version a lot of times just by road-testing things. You don't have to scream and shout and stamp about everything. I get down the road sometimes and I look back over my shoulder after a year. You catch your movie out of the corner of your eye or maybe it's released later on and you find yourself trying to recall why you got so upset about things at the time. You're asking yourself, "Why did that seem so important? This is all fine and I freaked out and went to the mat for that. But in the end I can't really remember why it was so important." The movie plays fine and it's a dance, but I think it's more important to support the film, support the director, and keep everybody engaged and heard.

It's a tricky job. The hardest part of teaching editing to students is the politics, because in film school, you're taught to stick up for yourself and you go with your gut. But nobody really teaches you about all the people that you have to keep together. It's a long road of getting a movie done and you're gonna have to stare these people in the eye at the final mix and you can't just blow things up as you go. You also have to bring harmony where there's a lot of disharmony. So I think it's only part of the job to do the creative stuff in your little woodshed and editing students just think, "I'm gonna come outta here and be an editor and I'm gonna stick up for myself and I'm just gonna be the loudest voice in the room." But that's not really the whole job. There's so much UN politics to it. In the end, it is a creative thing because it begets the best film. You can open people's minds and have them embrace ideas or have them sign off on things or get used to things. If you do it gracefully and empathetically, you can impact the movie in an early positive way by being coercive, by pitching your idea and getting through and sticking up for stuff. It's a lot of responsibilities.

What do you think the value of audience screenings is? How do you feel about them?

What do you think the value of audience screenings is? How do you feel about them?

CHESSÉ: What I've learned about audience screenings, and I've learned a lot about that from Marc Forster who's very shrewd and really plays the chess game well, is that the test screening for you as filmmakers should only be about the film you're trying to make and you should only be concerned with the feedback that you're getting that influences and supports or negates the things that are in line with your intentions. A lot of what you get back at a test screening is wild card ideas from audience members who don't know the movie and say, "I wish they left on a hot air balloon ride at the end." Or just crazy notes that the studio sometimes asks, "Yeah, what about a hot air balloon?" But you argue, "No, that has nothing to do with our movie. The audience notes become a tool for the studio to get their agenda across or to get them excited about the potentiality of what the audience might whim, they might want to, might wanna see on screen. Marc has taught me to read between the lines, look at the note behind the note, figure out what people are saying, and basically decline the notes that are not applicable and apply the notes that say you've missed something or you're getting something wrong, or that people are interpreting things a certain way that you don't want them to.

Covering up those, I think you have to be selective, but I think they can be really illuminating. But really only to you guys who are really in the dugout of the film. Not on a broad scale, "Let's talk about this at a giant table conference, Zoom meeting with a hundred people from the studio that you've never met before." They should be ingested and taken in an intimate way with the filmmakers, and they can be really illuminating, but they can also be used to roll over you. It's an art form. The test screening and taking in the test screening and applying it to the movie or resisting applying it to the movie is really a learned art form.

It takes a lot of steel to forward that stream properly and not get sucked into the rapids of opinions. But we read all the cards and we don't just look at the numbers, we read the comments and we really try to glean what that stuff is, because I feel like if you poll a hundred people and two people say, "I didn't understand this," they're not the only ones. Everybody who watches the movie has a note and has reaction from your partner, your assistants, and anybody's impression at the moment, anybody's knee-jerk impression is probably gonna be echoed through the thousands of people that'll see the movie.

That isn't the only person who's gonna come up with that notion. If you do your own data notation and you track those impressions from the friends-and-family cutting-room first exposures all the way down to a big group of people at a mall somewhere in New Jersey, you'll see trends and you'll see things and you can, you could actually bring them something back around and remind the director that's exactly what this person said two months ago.

I wouldn't say that's an off-base thing for people to be saying that. It can actually help you sell an idea if you've got a solution and your director's not accepting it. You can find compatriots for that by listening to what people say and arguing, "This is the fifth person that said they didn't know where they were when this happened. I think we should go with that other thing that you thought was too obvious, that let them know where they were." It can help you settle a bet if there's something that you're pushing for. They're not always to be refuted, they can really be embraced and interpreted and be used for a myriad of purposes in selling the best version of the movie.

It takes a long time to come to that place. I wouldn't say it's easy. It's like a firing squad. But if you figure out what it means to you and you figure out what you can do with it in the long run, it can, you can really flip it 'cause it's potentially a pretty gnarly experience. I think that practice and restraint and squinting your eyes and squinting your ears you can learn a lot.

Matt, thank you so much for a really illuminating conversation. I really appreciate all the time you spent with me.CHESSÉ: This was really fun, thanks so much.