Today on Art of the Cut, Adam Gerstel and Laura Jennings discuss Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania.

Laura has had a long career as a VFX editor on films like Sherlock Holmes, John Carter, Skyfall, and Pan. She’s also edited features including Edge of Tomorrow, and Maleficent: Mistress of Evil.

Adam has been a guest on Art of the Cut before with The Lion King and The Mandalorian. He’s been a VFX editor on films like The Aviator and Eat, Pray, Love. He’s also edited features including The Jungle Book, and Transformers: The Last Knight.

Ant Man and the Wasp Quantumania with editors Laura Jennings and Adam Gerstel

You've got this cold open starting in the quantum realm, and it is so much VFX. When you're cutting something like that, what elements are you using?LAURA JENNINGS: That sequence was actually there. She was walking on a set. There was a lot of design of the cave-like area that she eventually ends up in, essentially an extension, but there was actually a lot more there. It was actually a Volume situation as well, so there was a lot of the interactive lighting, etc.

The stunt team that we worked with had put together some stunt vis to figure out blocking. Michelle [Pfeiffer] was fantastic, she did a lot of that stunt work herself, actually leaping off things. So we ended up with a stunt vis sequence. I think at one stage, there were more creatures than ended up being in there, and she did a bit more interaction with them. But then, as the process developed, we realized we needed to make it a sort of short, sharp action beat so that Kang's last-minute savior moment could be impactful.

She was not surrounded by blue screening or greenscreen in that scenario. It was a good example of how the Volume really worked and integrated the set that she was standing on. The only thing that was markedly different was that we had guys in blue leotards with reflective helmets chasing after her on their hands and knees, which then eventually became replaced with beautiful work of these quantum creatures dividing.

ADAM GERSTEL: Both Laura and I started as visual effects editors, so our shared knowledge of that space helped not just with that sequence, but sequences that were just blue with a single actor, or a mocap actor or purely animated characters that weren't even a facsimile on set. We were able to put these things together knowing how to work with animation and vis and putting those things together - just picturing what it's going to be like and in some cases doing our own comps.

We would try to do things ourselves in After Effects. We would just mock it up and then send it to the postvis team. We had a very integral relationship with previs and postvis with The Third Floor. We were involved very early on in the process such that the stunt vis being traditional stunt vis, but also stunt vis being previs, we were part of the edit that would then feed what we shot, and then ultimately what we cut. But nothing was just handed to us. We were integral in putting that stuff together ahead of time so that we would be very familiar with all the parts to it.

There's nobody better than being able to do that than the two of you with your backgrounds. Could you fill us in a little bit about where you came from before these films?GERSTEL: I started my career as a visual effects editor. It's very interesting where Laura and I both had the same reactions from people, "Oh, you want to be a picture editor, but you worked in visual effects. That's not a usual path," up until now. It seems to be more common now. I did a lot of previs editing prior to being able to do picture editing.

I did The Lion King, which is basically an animated movie even though it looked live action. Then Mandalorian with the characters and also the Volume before this.

JENNINGS: I didn't go to film school; I went to art school. Graduating from art school, I actually worked as an editor in documentary and news and television for maybe the first six or seven years. Then I knew I wanted to work in film, so I took advantage of of connections that I had that happened to be in visual effects. Although I did do some assisting work, one of the earliest I worked on was Children of Men with Alfonso Cuarón, then Casino Royale. So having been an editor in documentary then a visual effects editor in film, it took about eight or nine years for me to get back to picture editing.

For me, it always felt like it was where I was going. Not that visual effects was in any way a sort of sideline for me, it was a passion. But I always knew that I wanted to be picture editing those movies that I was working on eventually. It always felt like it was a sort of "essential string to my bow." But I had to be patient and work my way through being a visual effects editor, learning and garnering all that kind of experience to then hopefully be in positions as I was with Quantumania. Adam and I were able to pull on both those areas of expertise where they were really needed throughout the process.

Adam was saying he'd done Lion King, and there are sections of Quantumania towards the third act where it really does essentially become an animated movie. It pulled on all of that expertise.

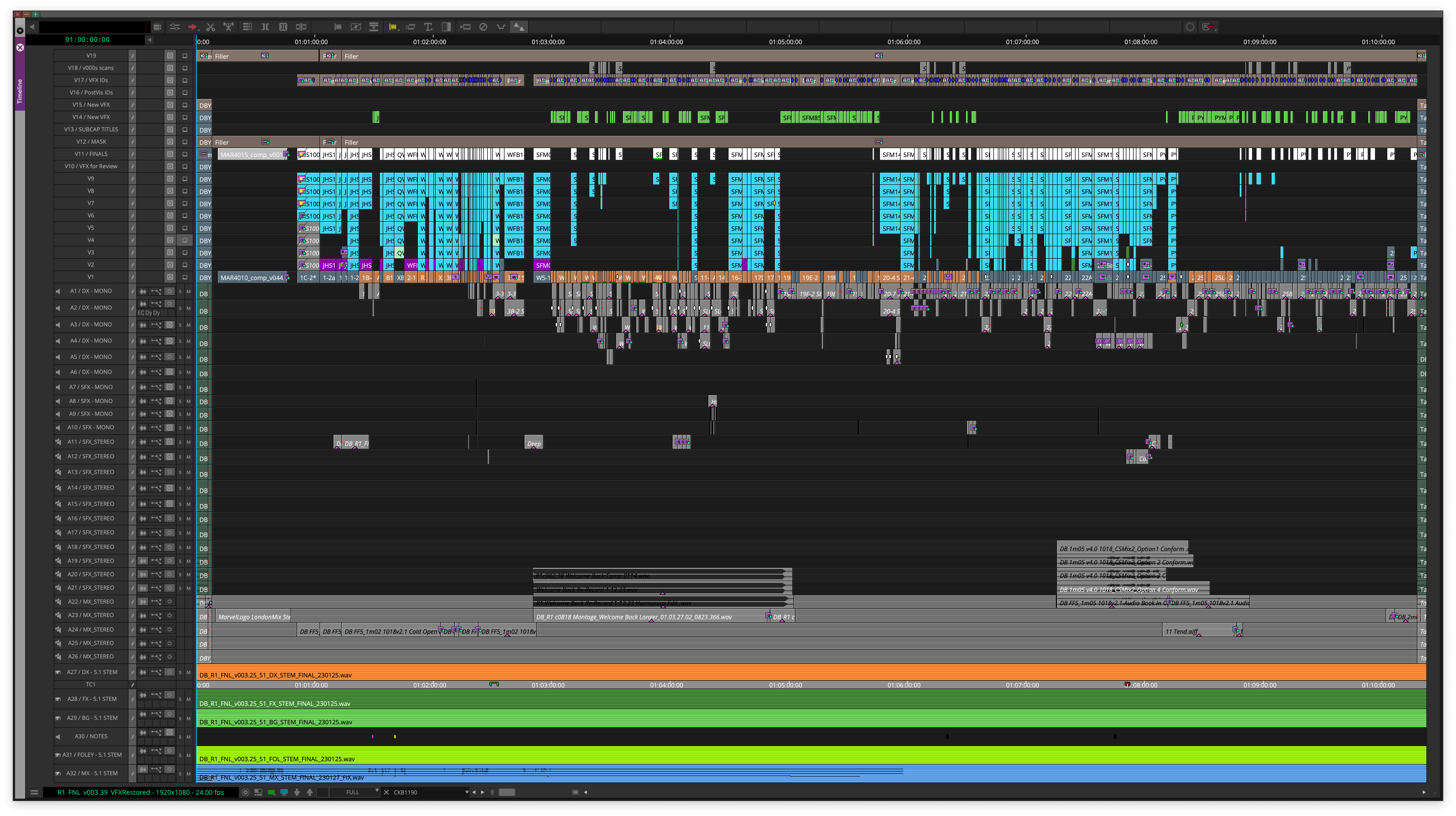

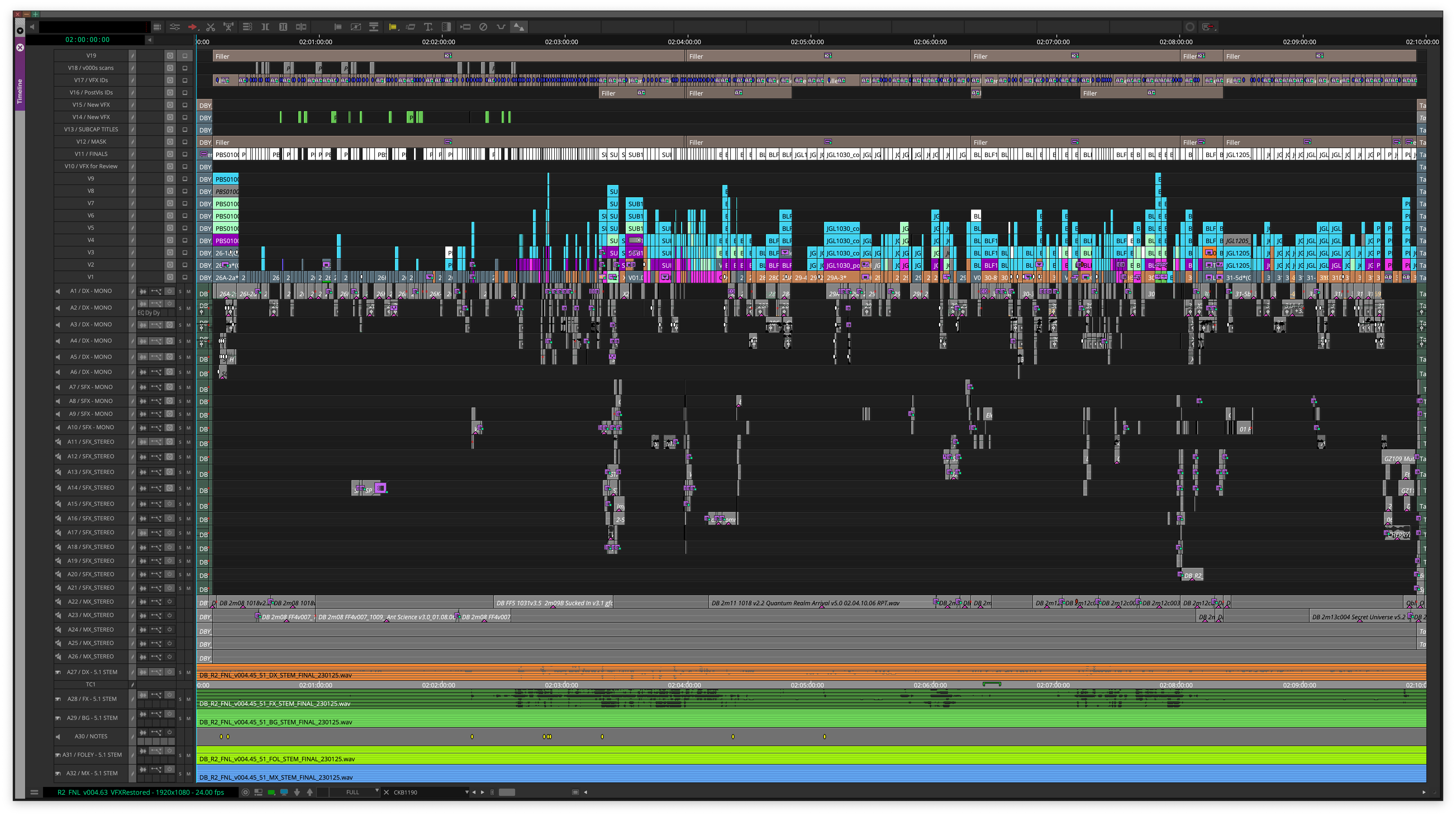

Timeline screenshot from the Avid for a reel (20 minutes) of Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania

GERSTEL: Steve, you and I spoke when I did Transformers. The third act on this film was predominantly like that because so much of it was fully created from whole cloth being able to imagine what a sequence would be without having material in the edit. Sometimes we would use storyboards or sometimes we would use clean plates. But I remember specifically thinking back to those days of, "Okay, here's a shot. Let's just imagine what could be in that shot and let's put together a series of plates” so that you might tell a story later when it gets to animation.

That idea of being completely in your imagination, that's got to be fairly early in the edit.GERSTEL: Definitely early on. Although it is Marvel, so there's always things that happened at the end.

Laura, you mentioned the collaboration process between the two of you, and I think that's incredibly important. How did the two of you work together on this project?JENNINGS: I was in London, Adam was in Los Angeles, and we were gearing up to begin the shoot. I'd already spoken to [director] Peyton [Reed] and we'd got on very well. I already felt excited about collaboration with Peyton, then I talked to Adam and told him about how much of a fan I am of The Lion King. We talked about how to collaborate. For me, it felt very important to set out an objective at that point before beginning the process of dailies as to how we would go about collaborating.

We ended up in a situation where we were watching the dailies together. We'd have our team put together what we'd describe as camera rolls of all of the dailies. If there were multiple cameras, we'd lay out the multiple cameras one after the other. We'd watch through the dailies together on one screen and we had a separate screening Avid to do that. Then we had our separate Avids. So we'd come into this shared space and watch the dailies. We'd both have Bluetooth keyboards attached so that we could mark the dailies as we experienced them together.

From working with editors on Skyfall, I remember picking up on this advice to watch through everything. Watch through all the dailies regardless of selects or notes. Take them into account maybe after the initial screening, but have that moment of when you just experience the material first time around. Get a visceral initial experience, a reaction to the comedy, to the specific performances to think about emotional beats.

Director Peyton Reed on the set of Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania

Director Peyton Reed on the set of Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania

I felt like it was really important for Adam and I to experience that together. That moment as an editor when you watch through that material, is really the only moment when you're going to be reacting in that visceral sense to a performance or comedy or any kind of nuance in a performance. So we did that together. We would watch the dailies in the morning and then we divided the sequences based on schedule so that we were never in a position where one of us was sitting around twiddling our thumbs while someone else was working for a couple of weeks.

If there were two or three sequences being covered in a week, we'd split those up. We'd go in the afternoon, work on our sequences, and invariably that's as far as we would get. As it turns out now in hindsight, that was really the only time we are essentially working on the sequences alone, putting the initial cut together. If there was some downtime, we'd start to watch some early cuts together. Not many though, but I think some we did and started to talk about things. So that was the beginning of getting into that very collaborative part of the process where as editors, it's kind of unique because it's difficult to present your work to a fellow editor.

When you haven't worked together before, you're just trying to feel your own way through the material. But I think we immediately hit it off on that front creatively. We were able to talk freely about some of the decisions we'd made. Because we'd experienced all the dailies together, that became an integral part of the process for both of us in the end, all the way through. So we were very involved in all the decisions and knew every part of the material. Which obviously sometimes doesn't happen when you're working with two editors. One editor might take the tail end of a movie and another editor might take the beginning of the movie. We were never in that situation and we wanted continuity. I think that was big. In terms of the flow of the movie, we wanted coherence and we wanted to be in a situation where we really understood the decisions behind every choice.

GERSTEL: Then we carried that through as a very unique part of the process that we should talk about. Once we had done our own sequences and had put them all together, talked to each other about how things would go, from that point forward in the director's cut, we didn't switch rooms. It wasn't like Peyton would go between our two rooms. We did have two Avids that we would go to if needed. But during the time with Peyton, all three of us were in the same room the entire time. One of us would be at the Avid when it was our particular sequence, the other back at the couch with Peyton being a different set of eyes and you'd experience the edits in a different way where all three of us would talk.

Editor Adam Gerstel

Editor Adam Gerstel

We were what we called, "The Brain Trust." We would go through the edits together. All three of us would air out any ideas or notes we had so that when we walked away with an edit that we were ready to turn over, we had all gone through the sequence very intimately. Especially because of the fast-paced turnovers and high-pressure visual effects of this film, we wanted to make sure that there was never a time where one of us would say, "I have an edit note for that." Laura and I discovered early on that we had very similar opinions about things anyway. But we wanted to make sure that all three of us had the same unified idea, sensability, and perspective on a sequence so that when a question was asked, any of us would have the exact same answer or opinion about it.

These Marvel films have two editors for a reason. It's so much material to get through and so many different versions you try. Even in our studio reviews, we would be in the same room together. We would not separate. We always were familiar with the dailies, the cut, and the versions of every sequence so there would never be a surprise. It would never have been, "Oh, you know, what we talked about when you were in the room was something that affects your character in a scene that you're doing later." We knew everything. Especially when it comes to structuring the movie, when you try things differently, it affects other sequences. So having that process where all three of us were always together being intimately familiar with the structure of a film was a key asset to being able to accomplish something like this.

I think it's the first time I've ever heard of a multi-editor project where you watch the dailies in the same room.GERSTEL: We wanted to talk about it, we would laugh at the same moments, and we would do our locators. We'd always compare when we located the same things since we had two different colored locators.

Did you find yourself talking a lot during the dailies?

Did you find yourself talking a lot during the dailies?

GERSTEL: Absolutely. We would stop and talk about things. As Laura said, when we would look at each other's cuts early on. One of us might say, "Oh, you know what? Did you try that thing? You know what, let me try that." Because we had seen all the dailies together, we knew all the different performances from each other's sequences.

Obviously Adam, you won the battle of, "Do we call them dailies or rushes?"GERSTEL: I guess I won that! The Americanism won out there.

JENNINGS: I often slip up and call them "rushes," and I vacillate between liking rushes and liking dailies as a term.

You can call them rushes in this interview, absolutely. I'm assuming you used the American slating system and not the British slating system?JENNINGS: Indeed, because I'd be mad to use the British slating system. We would've been in the thousands and maybe even tens of thousands.

[The British slating system adds “slate #” to the scene# and take#, and does not use letters to indicate new set-ups. Also, the slate # increments for the entire duration of the film’s production instead of resetting at the end of each scene.]

I want to talk about one of the early scenes where all five of our main characters are in a lab talking about ant science and the quantum realm. Every movie has at least one, if not multiple, multi-person scene. How do you deal with the eyelines, who to be on, reactions, and shot sizes?GERSTEL: That was the one I cut in dailies. It was a scene we shot very early on in the process too. That scene existed in different versions of the script. At one point, it was outside of the house, another point it was the basement. There were always different things, but it was always Peyton's intention to get the cast together early on in the shooting process and get them all back together again. In a way let's get the actors back to their relationships. That scene in particular was also just about whose perspective it was.

It starts out as Cassie presenting this thing and trying to create the relationship between Cassie and Scott [Lang]. At the beginning of the movie, they're a little bit on the outs because he picks her up from jail asking, "What are you doing without me knowing? Why am I picking up from jail? Why don't I know what you're doing? Why don't I know you have a suit?" I tried to delicately maneuver that relationship and that tension. Then it quickly turns into Janet [Van Dyne]'s scene because the whole thing is really about Janet realizing, "Oh no, they are doing this thing that is going to get me caught - or get us all caught - into this life that I lived that I have not wanted to tell the family about."

We set up early on that she is withholding information, but how much can we let her keep withholding? How much does she have to tell? In constructing it originally, it was always about just laying out everybody's perspective of the scene and getting the right shots to cover whose perspective of the scene it was at any given point.

As soon as Scott and Cassie have their tender moment, I remember specifically trying to get those POV shots of Janet seeing the device and thinking, "Oh shit, what is going to happen? What did you do? You have no idea what you've done." Then letting the chaos ensue once the device turns back on.

There was also a little bit of creating relationships between who was working on the device. There was a shot early on where Cassie was talking about the device and making sure we had a shot of Hope looking fondly at her. Implying they were working on this thing together even though Scott didn't know. Then Scott looking back at Hope and wondering who was working on what? Who knew what? Then it ultimately comes together and the cover is blown in the most chaotic way possible because we're all getting sucked down into the quantum realm.

Editor Laura Jennings

I love the idea of the building character, not just with what they say, but who's looking at who and showing relationships visually.

Editor Laura Jennings

I love the idea of the building character, not just with what they say, but who's looking at who and showing relationships visually.

JENNINGS: Oh, absolutely. That's a mantra I've frequently used. Acting is reacting, and when you have a true understanding of the motivation behind the moment or the script or what actors might bring to a given performance, it's all about when you cut to those reactions.

When you're dealing with a secret that some of the characters may know and some of them don't, it's my favorite thing to do. I'll often have to check myself, "Am I spending too much time on the person who isn't talking?"

GERSTEL: But you know too much as the filmmaker.

JENNINGS: You're going as an audience member, and certainly I feel that you're gonna draw far much more meaning from the dialogue if you're seeing how the performers are reacting to that dialogue, as opposed to just cutting to whenever somebody is speaking the line and that's where you draw the meaning from. To a greater or lesser extent, that's always a dialogue you are having with yourself as an editor, particularly in those scenes. Obviously, it's a whole other ballgame when you're dealing with action sequences. Dialogue - when you have inactive participants - is always a good giveaway in terms of the experience of an actor: when you can see how the actor is processing what they're hearing and really knowing that they know what their character's motivation is.

GERSTEL: I remember later in the cut, I felt like we were trying to create a relationship between Janet and Hope and trying to mend that because it started in the aside before the pizza scene. But I remember us finding a moment of Hope looking to Janet when they were interested in what Cassie was doing. Trying to create tension in, "Oh Janet, why aren't you interested in what I, Hope, have done or are doing?" We're creating a moment there through just reaction, when we choose to cut to that character, and at what point. When do you choose the reactions? When do you choose to cut to the character actually saying the words?

I find that you resonate more with what they're saying when you see their mouth saying it. If we're trying to get information across and it's very important, make sure we're on the character at that particular moment. Make sure we're not off them when you need to hear something. It's like people don't hear them saying it if they don't see them saying it.

What kind of discussion was there about how long you could sustain not showing Kang and maintaining the suspense? What's the right amount of time before he shows up?GERSTEL: This was a big conversation.

JENNINGS: It was an ongoing conversation through the process. When we did screen versions of the movie where we did not have the prologue that talked about with Kang, it was interesting at one stage. It really changed how you understood Janet's character very early on in the process. Anyone who's worked on a Marvel movie will know who they're going to be getting at one stage in the movie. It was much more interesting for the audience to know that Janet was withholding information. She was lying and there was more down there than she was telling her family about. We were able to present some of the relationship between Janet and Kang at the very early part of the movie, then a very big drum roll to the character of Kang.

It was a long script. We were talking about sequences that we dropped. There weren't very many, but a lot of the scenes were a lot longer. So just in terms of screen time, I think we got it down a fair bit in terms of when we first tease Kang to when he's actually back in the movie. We don't present him in real time until we've actually described more of his backstory. We go to a long flashback to extrapolate what we teased at the beginning of the movie.

GERSTEL: It's interesting to talk about the flashback because I think when we first were putting it together, it was a very long flashback. This is a very long sequence to go into some other story entirely and it comes so late in the movie. I remember when Laura and I first watched the cut. When we first put all of our scenes together towards the end of the shooting, we were actually surprised by how well the flashback played and that you as an audience member are starving for that information.

You really want to know who Kang is, where he came from, and you lean in. It felt shorter than it was because you really wanted to know. Yes, we were trying to be cognizant of how long we waited to introduce Kang, but we also wanted it to be a fair enough time that you are really ready to do that. We also were careful about not just when we see him, but how we mention him. "Who are you so afraid of?" When Krylar, Bill Murray's character, mentions him in the restaurant, it's all "him" and "he." Jentorra says, "If you're here, then he knows you're here." Yes, aside from the prologue, he wasn't visually in the movie, but his presence was in the movie. There were times in the early script where he actually came down at one point, I think during the guerrilla village at the same time as M.O.D.O.K. That was never shot. But we realized, "No, we've got to push him off. You've got to really let us earn his entrance into the movie.

How long was that assembly? Do you remember?GERSTEL: Under three hours!

JENNINGS: We're both so proud to say under three hours. I was saying to Adam how much I don't like the word "assembly." Perhaps because I used to push things around a little on a timeline a bit more like a documentary editor. I tried to take on some advice that was given to me fairly early in my career when I was working on Casino Royale and Skyfall. Watch your dailies and really get a good sense of the choreography of a sequence blocking-wise and approach the timeline with the confidence of knowing how I want to pace the sequence, at least in the first instance.

It's been a while since I've put something together that feels really loose. I liked us going in there and doing a pretty tight cut. Aside from the fact that, as Adam mentioned, you don't want to put a scene together and present it to the director as your editor's cut, where there's huge swaths of the script that you've skipped over.

I wouldn't ordinarily do that at all and didn't in this instance. But in terms of actually getting the pacing to a place where it feels right, I applied in this instance as well in the sequences with Jonathan [Majors]. His performance was very metered and carefully balanced. It felt like there was a really good pace that had a musicality and felt quite natural in his performance. So some of those sequences really didn't expand and contract very much at all, other than the fact that there were sections of dialogue that we knew we needed to extract.

What to call an “Assembly” is difficult. Calling it a “Rough Cut” is actually even worse. Calling it an “Editor’s Cut” is certainly not right, since you can’t actually cut stuff that you may want to cut. So what do you call it?

What to call an “Assembly” is difficult. Calling it a “Rough Cut” is actually even worse. Calling it an “Editor’s Cut” is certainly not right, since you can’t actually cut stuff that you may want to cut. So what do you call it?

JENNINGS: You're absolutely right, Steve. There really isn't a word.

GERSTEL: It's the "first version" of the movie. Or it's the "version one" cut.

V1, all right. So anyhow, under three hours.GERSTEL: We were proud of under three considering the script. Just in page count alone suggested that it would've been three and a half.

What was the page count?GERSTEL: It was around 215 pages. It was hard because there were a lot of half pages colors.

JENNINGS: But also long, expository stuff for action that wouldn't necessarily equate to a minute a page.

Let's talk about intercutting between the storylines. You are intercutting back and forth between Paul Rudd's character with his daughter and the rest of the family. Was that as scripted? Did you find places where it worked better?

GERSTEL: We certainly had a scripted version and, as Laura was saying, early on in the version 1 cut of the movie we tried things. This was one of the greatest things about working with Peyton, who was so collaborative and also so accepting of hearing other ideas. We wanted to try things. There were things that we showed him in that version of the cut that maybe weren't exactly the way it was in the script. Then during the director's cut, we continued to find different ways of intercutting. Because we have that flexibility of two separate groups at different points, we can play with when we cut to one, when we cut to the other, breaking things apart, putting them back together.

JENNINGS: We still had a couple of occasions when, within one intercut for example, we were maybe toying with a time cut as well in order to get around those things.

GERSTEL: We wanted to make sure that audiences weren't feeling like they were spending too much time with one versus the other. We would actually do a thing where we would look at the reels and just see the scenes visually. You want to start equally. So if we were with Scott and Cassie for this amount of time (showing his fingers far apart) and then we're with Janet, Hank, and Hope for this amount of time (uses his fingers to show “closer together”), the next time we're like both this (uses his fingers to show “even closer”) and then shorter (pinching his fingers together even more) as you're going back and forth, but you're not spending too much time.

The jungle scene where Janet, Hank, and Hope land - I think as scripted it might have been three times that we were in that set. We ended up making it two because it felt like we weren't progressing. We wanted to make sure that we at a pace that felt like you were moving while also not too fast to be able to experience. Because this is, as you get into the quantum realm, very much an experiential story where this is a whole new world that no one's ever seen before. We wanted the audience to come along in that journey.

You can't get through it too briskly. But at the same time, you want to make sure that you're servicing that it is an Ant-Man movie. You want to make sure that we're with Scott as often as we need to be. You don't want people asking, "Wait, what happened to Scott?" So balance was something we played with all the way through the process.

JENNINGS: Particularly in those earlier parts of the movie, you've first arrived in the quantum realm and it's visually arresting. You also want to get the feeling and move the story along before we meet the Freedom Fighters - Jentorra and Veb - and do the "rug pull" with actual characters that exist down in the quantum realm.

We had to make it feel like the two parties were experiencing things concurrently, but gave enough time for you to take in the worlds. A lot of that was done before we really developed what the environments were going to look like. With the jungle sequence, there was a lot more life that was to come. I think it's a really successful sequence in the movie where there was a set, and then the vendor had created all these wonderful characters and things moving around in the backgrounds, quantum creatures up in the trees. We didn't have that for a long time, not until very late in the process. There were a lot of those things to take on board as well as some of the drama playing out between Janet and Hope. Then, as Adam was saying, getting enough screen time with Scott and Cassie.

Adam alluded that there are some scenes that it's just all effects essentially. Something like the probability storm was something that I watched thinking, "I don't even know how you would edit this." What is your source material for a scene like that early on? I get when you can see the craziness of the scene and the VFX. But at the beginning, what is it like to cut that scene?JENNINGS: I'm glad you mentioned that scene, because there's so many fun aspects to how we put it together. It was a sequence that existed after we'd presented our version 1 of the edit. We're working through the director's cut because technically we had to wait until we got back to Los Angeles to figure out how we were actually going to achieve it. It existed in a previous form for a while. We recorded Paul Rudd with a facial-capture headrig ad-libbing, doing jokes and doing this whole "Who's On First?" homage, if you like. We cut together the audio, which I found a really fun part of the process, actually. Getting the comedy, getting the rhythm and the timing with the comedy, which is obviously essential with all of Paul's ad libs to himself.

But it existed in previous form as we figured out how to actually shoot the sequence. Adam and I had worked during the shoot with Third Floor's talented previs and postvis team to put together the version. It existed in several forms before we could really get it to its essence, the idea of a probability storm, which I love. It's just my favorite sort of stuff. It's why I love working on things like Edge of Tomorrow and things where you've different scenarios and how you can visualize that. It's a heady sequence that's conceptual and I find that so much fun.

After playing around and getting very "kids in the sandbox" with Third Floor, how are we actually going to shoot this? So we took some time to figure that out. Adam and I were both on the set. It effectively broke up into the "Who's On First" section of it, then the section where he's physically running around and building the tower, through to the end of the sequence.

The first part of it was amazing to watch Paul on set acting to nothing and doing yet more ad-libbing. Between Adam and I, we'd bring the material into our Avids on set and start to build up those layers of different Paul Rudd’s. Then Paul would come and Adam or I would present where he'd got to. Maybe there was one or two Paul’s in there reacting, and then he'd come up with another idea that he could put in there. "What's he saying? What's he saying?" All this fun stuff. Had we not been there on set, I don't really know how we could have achieved it in that way because he was ad-libbing against himself as he was coming up with different ideas.

In order to get the timing right, we were exporting that and then playing it back in an earwig (wireless earpiece) so he could hear himself and different versions of himself. I think he'd done something like that before where he'd done two versions of himself, so he had some experience of doing this kind of multiple past versions of himself. But not to the extent that we ended up doing it where there's hundreds of versions of Paul Rudd out there. I think we did it in the best way we could. Technically, we couldn't have done it if both Adam and I hadn't been there on set to allow him to react to the layers as they were building up.

GERSTEL: We had to commit to decisions. We had to make calls on the set that Peyton would agree to, and of course we could make some changes in the end. But because it was motion control, it was also very tied into timing and we had to make those decisions for what ad-lib lines he might react to.

JENNINGS: Then the section where he's actually running around and falling and reacting to pieces of him falling down. We had a rough idea and he'd obviously seen the viz. So he is able to bounce off the vis to a certain extent knowing what we'd visualized to begin with. Then we had a rig built that he could climb up that would eventually end up being versions of himself that he's climbing on. We had a bunch of guys in blue manhandling him, pushing him up, and then he'd change into his Baskin-Robbins outfit and he'd be running on a treadmill. It was fun. It was as wild to put together as we hope it is to experience in the movie.

One of the things that I'm always struck by with fantasy type movies is that editing is so much about truth, yet you've got these fantastic situations and you're trying to describe crazy quantum universes. How do you orient yourself to the truth of the world that you're trying to build?GERSTEL: Having an understanding of what each scene was. Although we did continue to develop the actual look, and as Laura said, the jungle in particular throughout. But understanding the tone of each environment that you're in, "Is this a scene about wonder or is this a scene about threat?" and making sure that the perspective of that particular part of the quantum realm was true to the story and to its place and the narrative. There were lighting cues to some extent that used those stagecraft volumes that the actors could see. Just through the narrative and what was ultimately serving the narrative, serving the threats, serving the wonder of it all and weaving that together to tell the story that led to Kang. It was interesting because really, all that stuff led to Kang. Once Kang was introduced, the film becomes a different story. It becomes the Kang story. But up until that point, it was understanding, getting your bearings of this place that no one's ever seen and in the other film saw a totally different version of it, which we like to allude to. What you saw before had nothing to do with what the quantum realm really is.

We're making sure that we're true to each part of it and all the inhabitants of the quantum realm. Understanding the Freedom Fighters, "are these friends or are these foes," playing with that sense. When we're first met with the Freedom Fighters, they're a threat. Then one of the funniest moments, when Veb, who's played by the genius, David Dastmalchian, comes up and all the conversation about holes, we realize that these are just friends in the buildings that move and understand where we are in the tone and the narrative.

JENNINGS: I found myself approaching this Marvel universe in how much it reminds me of classical mythology. It does take a while. I think it was tricky for a moment for me, the beginning of the whole process, not ever having done a superhero movie before. To get into that place where especially when you put the sequences together and maybe the suits make some noise, they're a bit squeaky. Things that you just don't think about. Oh my goodness, am I going to be able to get through this barrier? The truth is, just as you can become completely engrossed in any of the classical mythologies - all the deities and the gods - the more you engross yourself in that world, the more real and truthful it becomes.

As soon as you get rid of those little squeaky sounds in the timeline, replace them with some room tone, you're getting more than halfway there. I hope that you really get engrossed in the mythology of each of the characters, whether it be the cast you've been involved with for the other two movies, or new characters who are on the scene. Hopefully that's the thing. It's the level of escapism within fantasy that is wonderful. But you still have to follow some rules.

I think some of the difficult things about first putting together the probability storm was that you still had to base it on something that was believable to a degree. Or the rules had to make some sense and then that grounds you. I would apply that to all the other kind of movies that I've worked on where it's sci-fi. Any of those things where you are world building and you take the audience with you, hopefully the audience is never left thinking, "Well, I can't really believe that would happen."

GERSTEL: You have to create your rule set within the world of it all being fantastical. You can break the rules at times, but you have to know what those rules are. So that even though none of it makes sense, you could go with it as an audience, live in that world, and not feel thrown by it.

You've also got the grounding of the family relationships, of course.JENNINGS: Which in every sense, are applicable to fantasy, sci-fi, and everything else. You've hit nail on the head with that. The things that appeal to us as humans are the things that can exist across so many genres of filmmaking. But it comes back to those human experiences.

There are huge tonal transitions. How are you navigating transitions between terror and comedy?

GERSTEL: What we try to do is look at the film always from a 50,000-foot view. When you have a long version, then you start taking things out, you have to constantly be checking yourself about when you are doing the action, when you're doing the comedy, when you're doing the threat, when you're doing the emotion. So that you're not always leaning on one too heavily. It's always serving the overall narrative. We found that as we took things out, it made other areas feel too long or feel too much time without comedy. We always had conversations of, "Okay, when was the last joke? How long has it been since we've laughed and is that a good thing or is that a bad thing?"

You want to make sure there's enough time so that when Scott comes out with the anger of, "Where's my daughter? We had a deal!" that doesn't come off of a joke. That needs to be resonating and you need to earn that. We had these conversations all throughout the process of how long are we taking this through? How long is this scene? When was the last joke? Should we have a joke here? When is it appropriate to have a joke? Who has the joke?

You don't want to take anything away from Kang's power by having a joke. M.O.D.O.K. was always a tricky one because although he is a threat, you want to allow the audience to know that they can laugh at him. He is a comedic character. It's about who you can and can't laugh at. We certainly played with all those things throughout and found our way, pacing-wise and scene-order-wise in order to allow those moments.

JENNINGS: It was a consistent challenge, as it always is with movies. Particularly with the comedy, finding the tone of the movie, and taking the audience on that journey where they don't feel like they're being pulled in too many different directions. That was tricky. As Adam said, the tighter you make the movie, the more intense those turns need to be. The audience needs to be okay with being taken on that on that journey.

We were finessing it and adjusting those tonal shifts all the way through the process and certainly through all the screenings. I think some of the things we landed on was through pure experimentation. For example, it was better for Kang's character to not interact too much with the very comedic characters in the movie so that he could maintain his threat and his presence. So that by the time he's out there on the field killing people, you're terrified of him. We had found that with Jonathan's performance, we wanted to keep him really controlled. So that when he does explode at these tiny moments in his performance, you really feel terrified, but also that the strength was when he was holding back a little bit.

Did he give you those differences in temperature in performance?GERSTEL: Oh, absolutely.

Then you had to regulate it. You had to decide, "Don't have him be too hot, let's have him be cooler."

JENNINGS: Obviously, Jonathan really, really developed that particular performance. This is such a unique thing for an actor. He's in this position where he's already played He Who Remains in one particular way, and he's coming into a new movie with a variant of Kang. But he's performing this particular Kang the Conqueror in a different way, and he very much came in with that in mind, but we were able to dial it. For example, when he'd do a head cock, and he might do that four or five times during a section of dialogue. We'd actually say, "Let's just use it here because it's delicate and it's specific." We got to a place where we'd maybe check a different take and say, "Oh no, that's not our Kang." So that was very interesting to go through that part of the process.

That was very different to how we dealt with Paul Rudd's comedic beats and how we dealt with Bill Murray. There were a lot of different, approaches that we needed to do because it's such an ensemble piece. It was very interesting and challenging at times, but really enjoyable.

Thank you both so much for chatting with me about this and good luck on your future projects.GERSTEL: Thank you, can't wait to talk to you again!

JENNINGS: Thank you, it's been great.