Today we’re talking with Oscar nominee and multiple BAFTA nominee Barney Pilling, ACE about editing Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City.Barney has been nominated for BAFTAs for his editing of Spooks, Life on Mars, and The Grand Budapest Hotel. He was also nominated for a BAFTA and won an ACE Eddie for The Grand Budapest Hotel. His other work includes Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris, Annihilation, and Suffragette. Also, numerous TV series including Outcasts, Playhouse Presents, and Mum.

Art of the Cut: Asteroid City

From your IMDB page, it looks like your career path does not include being an assistant editor.Pilling: It was very quick. I was an assistant for two projects, which lasted less than nine months in total. So less than a year of assisting. I was given a chance by people that believed in me. Basically, the tech crew at the Avid rental company did as much assisting on that show as I did because I was forever on the phone to them saying, “How do I make the Avid do this now? How does this work?” I was really learning on the hoof on the first one. That sort of continued into the first edit job I did. I was so green when I got my first edit job. You build relationships with these companies.

I was looking to have that with Hyperactive (as they used to be called, then they became HireWorks). Phil Kent – who was one of the tech guys that really babied me through an exceeding short assisting period. As soon as I could put things on the timeline and start being creative, that just swallowed my whole existence in a lucky way because of the opportunities I got. But I didn’t get into editing wanting to just be a technical/support role. It was a burning need to be creative. I was very lucky, and it worked out perfectly.

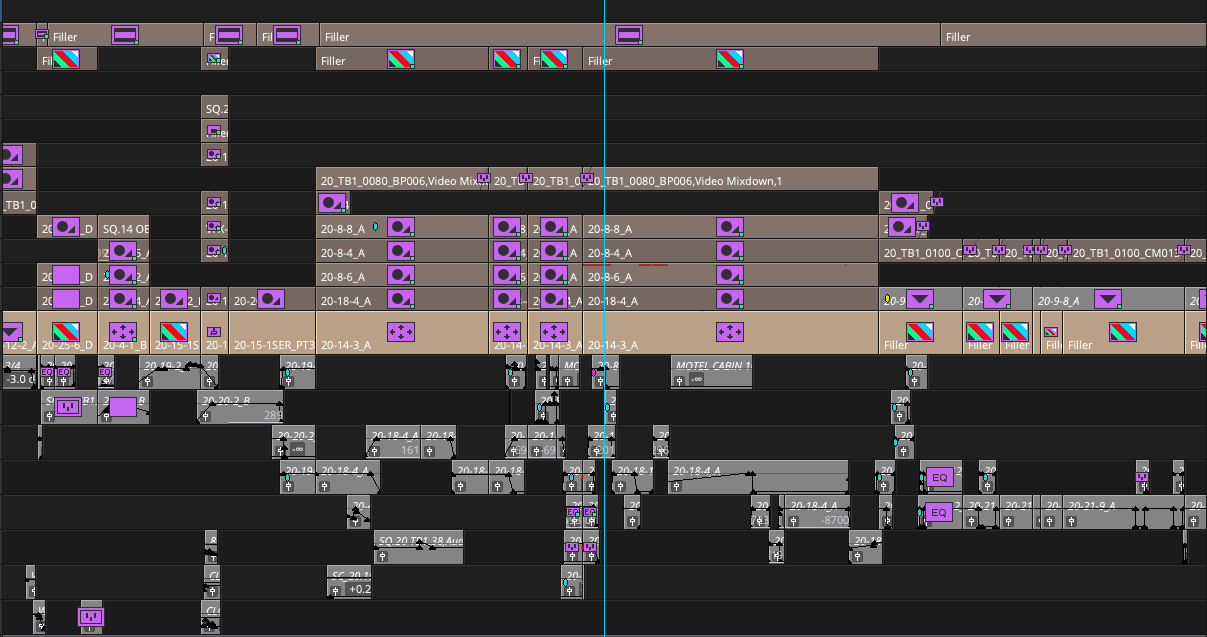

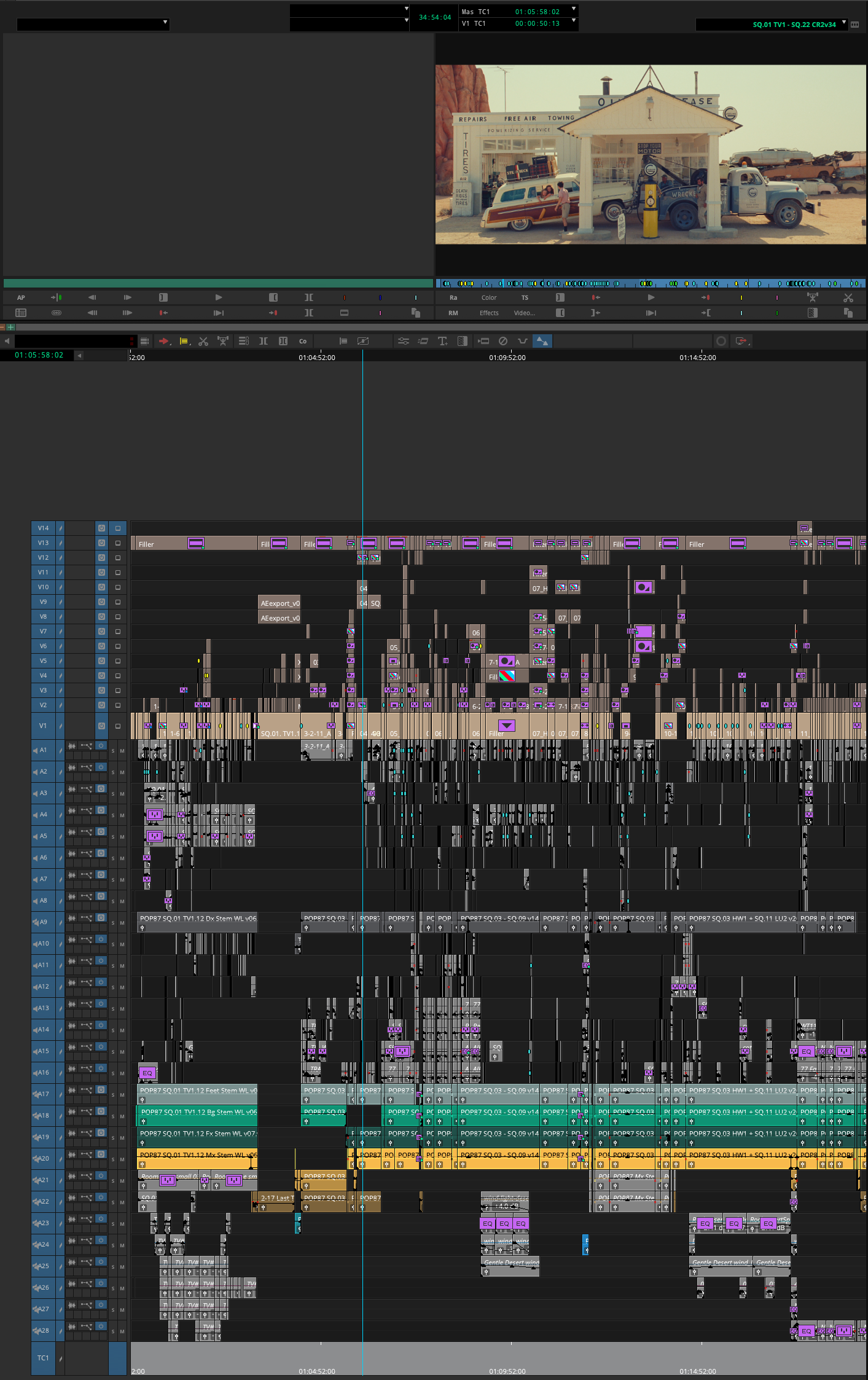

What was it – the relationships, the collaboration style – that made someone want to work with you at the beginning? Barney Pilling, ACE in his cutting room for Asteroid City.

Barney Pilling, ACE in his cutting room for Asteroid City.

Pilling: The first job in the actual edit suite I got came straight after my first job as a production runner. I was in the production office as a production runner for a production coordinator who is now my wife of 30 years - the mother of our children, in actual fact, just for full on serendipity. I was on for prep. It was the first job I'd done as a runner. I'd come from a background of making dance music digitally - so sequencing early Pro Tools, Emagic, Cubase, Atari 1080STs. I'd seen the digital timeline. I was pretty familiar with that, certainly for audio, but the concept is almost identical, you just add picture for the Avid.

I couldn't make dance music work. I wasn't good enough at that. I wheedled my way in on the very bottom rung as a production runner. We were in prep for probably six weeks. I was running around photocopying scripts or picking things up for the art department before the shoot got going.

Then maybe 10 days before the shoot date, my boss/wife said, “The edit suites are being delivered today. Can you help the hire company bring it all in and put it all together?” I helped them do it. I helped them unbox it. With every box that I opened, I just felt in heaven. I'd never seen an edit suite before and knew instantly - this is where I need to be.

It was a fairly long-running show. It was ten one-hour episodes. I was on the show as a runner for a long time. But in every spare minute I got – during night shoots as well, there were lots of long nights when the editors had gone – I bombarded them with enthusiasm, which I didn’t have to force. It was just natural. It was, “Can I have a go on this? Can you show me how this works? Please?” I was affable enough and helpful enough during the day and didn't get in the way, I wasn't over the top with it.

Detail - Avid screenshot of Asteroid City.

Of course, it was a location shoot. There were quite a lot of people up from London living in Manchester working on this. That tends to mean there's a fairly decent social aspect to the filmmaking process as well, so that they would all go out together. I lived locally, so I would go out with them too. We just became friends. They were incredibly supportive. Liana Del Giudice, Steve Singleton, Mike Jones – stalwarts of British television editing.

I attached myself to them and did as much as I could, spent as much time in there as I could. By the end of that very first job as a runner, they were leaving the Avids running for me on night shoots. They'd go home and say, “Look, we'll make you an area in the project so that you can't break anything. Have a go.” They'd show me how to switch it on. They'd show me the basics of the source monitor. I knew what was happening on the timeline that didn't need any explanation, but I needed a little bit of conversion therapy to get from Cubase to Avid.

Then in the mornings they'd come in and look at what I'd done. They would either credit me with it or say, “What are you doing with that bit? That’s not good.” That’s the very first and almost only official training I got in editing in a way. It was their guidance and their willingness to support an enthusiastic, affable kid who clearly loved what he was seeing in the cutting rooms.

One of those editors was going on to another TV show and he just said, “Look, you come and assist me. Let's do it.” You know, what the heck? I'm a quick learner. I care. I'm a digital kid, and I came from an environment with MIDI, signal paths, and sampling. So technically, it's not like I was inept. It was just a transference of skill.

He took a chance on me. He liked having me around. He'd seen enough in the rough scratch edits I'd been doing on the night shoot. He even said, “Can I use that one?” I said, “Of course you can.” He said, “That's really good. That's good.” He was true to his word. I did one more show with him. Then from that the director that he was working with hired me as the editor on his next show. It happened that quickly.

We're definitely a community. We look out for each other. It's always very open. When someone is polite, enthusiastic, and clearly wants to do the job that we all care about so much, you just want to encourage it. This job defines me.

I saw that this was shot mostly in Spain. Were you on location or near location? What's the benefit of that?Pilling: It’s part and parcel of what makes working with Wes very special. He treats the community – much like we just discussed – as a family. They are my second family now, after working with Wes for 10 years. It’s very important to him to protect the location that we’re at and the time we all have together. On one side of the coin, it can be brutally hard work, as we all know.

But the other side of the coin is to infuse yourself with this place that we’re in. Be social together. It’s active encouragement – not just for technical reasons – for me to be close to set. It’s for the community spirit reasons for us all to be together. Wes keeps a very tight-knit group. It’s utterly essential that we’re all together.

Screenshot of the Avid timeline for Asteroid City.

The other reason is how crucial it is when you’re in Spain and you realize six months into post production that we’re missing something or something doesn’t work. He and Adam Stockhausen have created a town out of nowhere, that we have to exploit for everything it’s worth when we’re there. Wes is able to come off set and say, “I’m not sure this is going to work today. I have a feeling about this that didn't quite work” or “Maybe we didn't get that dolly quite right. Let's really hammer that scene now and see how we feel about it.”

So we really intensely put certain scenes together. Now, we don't do that for the whole movie because a lot of it he knew on the day and then two days later when the film gets back to me (old school style) and I see it, you realize there's no problems here at all. So let's go where the squeaky wheel is. This other scene has a problem. Let’s rework it in the edit. That gives him and the first AD the opportunity to say, “Okay, that's no problem. We can slot another afternoon in on that set. Nobody struck it. It's all here. Let's just go and get that close if you think you need it.”

On French Dispatch, I talked to Andy Weisblum about the fact that there's an animatic of the entire film. Is that something that happened on this film?

Pilling: It began with Fantastic Mr. Fox, his first animated movie, where that's the heart of the thing for many years before the animation can start. On Grand Budapest Hotel we had one too. It ran out at about 81 minutes. It never got finished. Actually it did, but it got finished after we’d filmed because we can’t leave an i’s undotted or t’s uncrossed. But the animatic went through the big gun showdown in the hotel towards the end of the movie, in the third act, and then it ran out.

Was that an assistant who cut the animatic, or did you cut it?Pilling: No. Wes works with an editor called Ed Bursch.

He's the same one that cut the French Dispatch one, I think.Pilling: Correct. He does all of them. That's his area of expertise. He doesn't need to move. He can work remotely with rest with Wes at any point, even when Wes is in full production on another movie. He can be talking to Ed about the next one. He’ll even have storyboard artists. Ed’s brilliant with After Effects, so he’ll take storyboards and build in much more animation than just a moving a mouth. Obviously, it’s pretty clear that the camera dolly moves that we do are a huge part of the narrative storytelling device that Wes has in his voice as a filmmaker. In After Effects, Ed can really make these sing.

He's really good at sound design. It’s rudimentary sound design because it’s just a cartoon obviously. There’s only so much you can glean from it. But he and Wes worked on those for many hours and weeks before principal photography began. The spirit of the movie is there. Certainly the logistics of A to B with the dolly are there. That means when you’re on set six weeks later, you’re not saying, “Where should we put the camera?” They know where they’re going to put the camera.

Although the grip wants to strangle Ed Burch. He’s thinking, “How can he put a dolly move from there to there in a cartoon that lasts for three seconds? It’s against the law of physics.” It always takes a lot longer.

I think Grand Budapest Hotel was quite close. Certainly for Asteroid City, because we have some monumental dolly shots in Asteroid City, they all came in a lot longer than Ed could do them in a cartoon. The grips said, “ Oh please kill me here. I can’t do it that quick.”

While these animatics prepare what we’re going to be doing visually, they also mean that you’ve not just read the scripts. You can watch it. It becomes a much closer facsimile of the moving image.

Actually with Asteroid City’s animatic, it was done smack in the middle of the lockdowns. Wes first contacted me at the end of summer 2020. The industry was in a funny place then. I was doing smaller things from home. He couldn’t be sure which actors – if any - would be available or when we’d actually get to do this.

The French Dispatch release itself was delayed because all the theaters were shut. That film was ready to go a long time before it was released.

So Wes had quite a bit of time on his hands with the animatic of Asteroid City. It meant that he could start spit balling with Alexandre Desplat, the composer, who also wasn’t in recording studios. He wasn’t recording any musicians because of the lockdown. They were all just working from home – Ed in Pennsylvania and Alexandre in Paris separately.

As a result, the animatic for Asteroid City actually had Alexandre’s composed music on there. They were only demos, but they’d already started to figure out the tambour of it, and maybe some of the instrumentation too. It grew and changed and flourished and became a much more complex thing than it was initially. The seed for this movie was really well germinated before we got there.

That's incredible. You mentioned the precision of the dolly moves and how instrumental these shots are to Wes's style of storytelling. There is such a precision to those camera moves and to the compositions. How does that affect your editing?Pilling: Well, I have to immediately commend the grip, Sanjay Sami, and his team, because they jerry-rigged things. Some of these dolly moves with pushes in and out, moves this way and that, it’s not just a piece of track. It might be a latticework of track, a system that can come in and out or left and right. They’re geniuses. We don’t have motion control. So it’s not like we're just going to hit a button and do the same move twice. But they manage to land these things within inches of what I need in the cutting room.

So there’s a lot of vari-speeding to get an incoming and outgoing to match, because some of the huge dolly moves are actually six dolly moves that we’ve stitched together. Some of them are shot weeks apart with actors that were never actually in Spain at the same time.

What's an example of one of those?

Pilling: The big opening introductory dolly move that goes from June Douglas saying the prayer with the school kids right through to Steve Carell in the motel office as he hears Montana kicking the vending machine. It's a huge dolly, which introduces everybody.

It shows all of our characters effectively. Because of COVID and because of scheduling, our chances of getting something long to actually work are small. We’d still be there now trying to get all that to fit with the timing it does. With many scenes that are that big, you split them up. Basically, you end up editing shots before you edit the movie with Wes. You can’t just go in and say, “Okay, here’s scene nine, it’s a dolly move.” It was actually five different dolly shots with groups of action that’s been rehearsed to death.

It’s a bit like musical choreography. You want your dialogue and your extras so it sings like a Swiss watch that these movies do when they’re finished. You have to break them up. That’s how we do it. Sometimes it’s a necessity because we haven’t got a certain cast member – they’re not coming for three weeks, but another cast member is leaving in two weeks, for example. There’s more than just one reason to do it. So we would stitch them together and use lots of references on set, lots of photographs. Weather presents its own issues. The sun’s direction can make it look a little off. The sky in Chinchón was ever changing, but digitally we could help that. This is not to say that we don’t do some huge long dolly shots in a oner that work well. But with those really big ones, with every cast member and it’s all clicking away like that? No, we edit the shot first, then it goes in the movie, and then we edit the movie.

You mentioned editing the shot, which is interesting because these films are like a fine Swiss watch in their timing and their precision. Do you even do that within a single static frame? Are you doing split screens to put one performance on another side?

You mentioned editing the shot, which is interesting because these films are like a fine Swiss watch in their timing and their precision. Do you even do that within a single static frame? Are you doing split screens to put one performance on another side?

Pilling: All the time. It’s his language. Wes writes all these with Roman Coppola. It’s so much a part of his fabric, these scripts, because he’s built them. The cadence and rhythm of Wes’s humor is totally unique to him. We can approximate it. I can put scenes together when I think it’s about right.

But Wes has a metronome inside of his head that nobody else can hear. It’s only when it’s done with everything - the pointillistic approach of making sure that this little corner works, this little line works, that word doesn’t have quite the right rhythm, this side of the frame is not matching with that side – it’s only once we’ve tinkered or spruced that his intent comes into the cross hairs of his filmmaking vision. We’re constantly manipulating. Why not? The technology is there to do it. It’s not like we’re digitally making things up. We shoot on Super 35, there’s limits to what we can do. But by the same token, there’s an awful lot of freedom of having the dialogue marry with the camera moves to propel the story and narrative in the exact way that Wes imagined it.

Do you bother trying to set your own metronome that is like Wes’s when you're in dailies, or do you just go with the performance in a given take?Pilling: Mostly when we’re filming, I’m just cataloging or getting to know and become familiar with the range of performance. We do a lot of takes. When you do a lot of takes, each actor has their own rhythm of where the good stuff comes.

For instance, Wes doesn’t cut the camera if he doesn’t have to. We just tend to burn a whole reel of film without stopping. The footage itself is a behemoth that needs taming.

So mostly it's just dealing with that and getting to know it and then Obviously technically checking the dailies. Then as I alluded to earlier, the other time that is spent editing whilst we're filming, is spent really fine-cutting the problem areas or the areas where we think we might not have it. So some of the scenes that we've shot dailies for, we might not actually visit and put together until we finish filming.

Are those choices coming from Wes because he knows what he wants you to look at and what he doesn’t?Pilling: Yeah, to a degree. Or he says, “When we put this together, WE’RE going to put this together. Not you.”

Got it. Meaning you and him?

Pilling: That’s right. Wes can’t do it by himself. I can’t do Wes’s rhythm by myself. There’s no ego here. It was an adjustment on Grand Budapest Hotel because I’d never worked like that before. But when you see what's going on and you see what's involved in putting these things together, you have to parse that.

When we get these things together and watch it, there’s a lot of discussion because not everything works how it should, particularly with the complex narrative structures that we have on this. There’s a lot of tinkering to be had. It becomes an open forum of, “Hey, this feels like a state of the nation scene. So I think we should bring it nearer to the events that they’re all talking about. I think that’ll make it play better.” There’s a lot of experimentation that goes on after that.

Wes doesn’t just want to see an assembly of the whole film to see how it’s going. He knows how it’s going, he knows what he’s got, and he knows how it’s going to go together.

Our time is far better spent with me getting to know the material. So when we do get to put the scene together, he says, “In the middle bit, after the struggle of getting the line right, once we’d done that, so from take 16 onward it’s a really nice fit. Do you remember where he does this?” My biggest goal is to say, “I know exactly what you’re talking about. Let’s put it in there and start experimenting with it.” When I say we fine cut the scenes, we really fine cut. If there’s a perceived issue of a lack of footage or a performance he doesn’t feel is quite right, we will finish that scene. I do a lot of sound design as well. A lot of the sound design in the movies originates from the cutting room.

It's far better for us to spend our time really focusing on potential problem areas when we’re out there during filming and the dailies are coming in. It might even be that we’ll concentrate so hard on one scene I’ll be editing all through the day, while Wes is on set.

Then he’ll come home and we’ll watch it. He’ll give lots of notes and say, “We need to do this and this. Leave that with you. I’ll shoot tomorrow. Let’s see how it looks tomorrow evening.” So there might be three or four days that go by where we’re really trying to fix the scene and I’ll miss the dailies that are coming in because I haven’t had time to do it. So then I have to do this speed catch up.

From the fact that you've got this animatic and just from looking at the film, it looks like he would shoot with very little coverage. Is that true? It's lots of takes, but not so much coverage.Pilling: Wes does not like to waste time, money, or film with the animatic or with his ownership of the words that the actors say. The best thing for him is to know exactly where the camera’s going, and then it’s about harvesting as much performance material as you can get. It’s about giving the actors the broadest canvas to explore with the words, so they can come up with things that are interesting, heartfelt, unique, and surprising.

I think it was John Hughes who said about coverage, “That’s somebody who doesn’t know how to direct, because you make those decisions upfront. There’s no reason for coverage.” It’s a crazy way to think for most of us.Pilling: It is. There are a handful of directors of whom you could say that’s absolutely the case. Wes is a prime example of that. I think there’s a thrill in editing material that hasn’t been conceived in that way when I was in the cutting room and experimenting with what’s possible in there.

There were films by Steven Soderbergh or Michael Mann, and then a little bit later Paul Greengrass, where that’s abjectly not the case. Coverage is king, you spray the thing. Obviously, the documentary style lends itself to the drama infused in those films that they were working on, but that’s just as enjoyable. It’s just very different and you need coverage for that. It gives the chance for really flamboyant jump cuts and poetic cutting between takes that are actually the same set up, but slightly different because the camera’s in it. There’s a real dynamism that you can put into it that way, but there’s no room for that with how Wes constructs his movies.

There’s times when you say, “No. We can’t quite hold in the wide shot as long as we might have hoped.” We do need some coverage. There’s scenes where coverage was shot that we didn’t use, and there are scenes where we didn’t have any coverage. Then when we put it together, we said, “We better get that.” But largely, there’s the John Hughes approach. There’s a real distinct roadmap of what we need to get out there.

Did you use any temp score?Pilling: No, because most of it is source cues, which I loved. Most of it was the music of the period, interesting music of the time, just drifting in off a jukebox or playing on someone’s radio in one of the other cottages. It just drifts through in the desert air itself and steeps the place in the nostalgia of the era we were setting.

Wes has worked closely with Randall Poster for many years, our music supervisor who’s just a wonderful fount of knowledge and choice when it comes to source music like that. We had a huge array of wonderful music of the era to be playing around with. So in a sense, we temped with that.

The performances are very stylized. How do you look at a Wes Anderson daily and find that great moment or know you’re finding the right take?

The performances are very stylized. How do you look at a Wes Anderson daily and find that great moment or know you’re finding the right take?

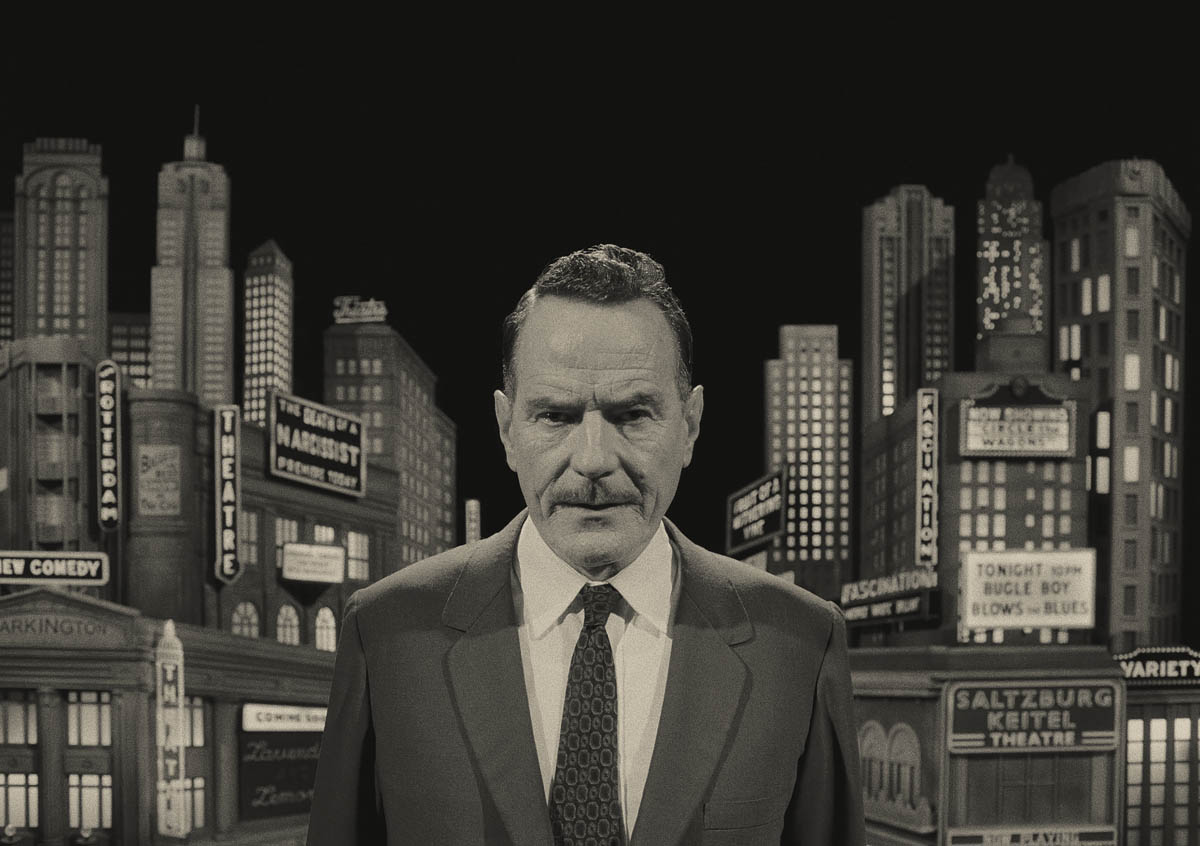

Pilling: That is the challenge of these things. The will-o’-the-wisp is the performance, and I think with Asteroid City even more so. It’s even more challenging to do that because of the dual narrative. Because of the fact that whenever we’re in Asteroid City, we’re assuming it’s within the layer cake of the narrative – they’re on stage, and they’re performing, and it’s a little bit over the top. So it’s even harder to gauge.

Is this just eccentric enough? Is it just flamboyant enough to support that narrative structure, yet grounded enough to keep it from looking silly? I think it’s never one take. As I discussed before, because most of the takes where you’re really looking for this are the emotional takes. It’s the overs and the conversations where the biggest emotional heft needs to be lifted. You feel it in the rhythm of watching that whole day’s rushes of that scene. You feel a hotspot. It’s never just one – all actors are different obviously, there’s a warming to it.

Sometimes there’s a struggle with a certain line. There are certain struggles in warming up that you have to get to, and then there’s a beautiful purple patch where you think any of these could go in. Really genuinely any of these could go in. Then it might tail off a bit and then at the end you might just get a wild one where Wes will always say, “Let’s do a couple for the pleasure.”

There’s a couple of instances when Augie is telling his children that their mother’s died. It’s at the first act, which is just beautifully quintessentially Wes for me. We could have done it a couple of different ways. There was a beautiful series of takes that Jason Schwartzman – who I just think is amazing in this movie – played it a lot more stereotypically emotional, and I really respond to that. You put it in there and you think, “Yeah that works on that emotional level.” But it’s really taken away some of the unique oddness and some of the black humor that we have to have in this scene. Not just because Wes excels at that, but just because we can’t overload the scene. Woodrow is becoming emotional, you feel for the three fragile children who can’t quite understand what’s going on.

If we had it on the other side of the camera as well, we’d just tip the balance of the scene into 11 instead of 10. We needed it at 10. So I wouldn’t say it instantly with one particular take, but you do feel the rhythms of a series of them. That’s a lot of fun. That is when you the scene or the bare bones of the scene or the backbone of the scene, because we can make two versions of the scene.

For instance, with that one, we made two different versions of the scene with a backbone of Jason from two different spells of when we really liked what we were doing. It was emotional, it was arrogant, and it was narcissistic. He’s such a wonderful character for Jason to play and he plays it superbly. It becomes a trade-off. It becomes a beauty contest. You say, “Do we like this one or do we like that one?” But it means you’ve got the backbone of the scene there ready to go.

I would think it's a tonal issue, right? You can't escape the tonality of the rest of the film and jump into a different movie just because you've got this great emotional performance.

Pilling: No. But Jason did it in a way that we really had to consider putting it in the movie. So, it wasn't so far off the page that you think that doesn't fit. It's a very intricate scene to get the tone right. For instance, my assistant and I would look at stuff together. Depending on her emotional attachments or the things that the VFX editor had been going through for the last year himself, you bring your own lens to it. You’d say, “I really like that take. That feels like that version is the right one.”

Then I see the narcissism that we’ve ended up keeping in that scene and think, “No, we’ve made the right decision with that scene.” I think that’s what pre-planning and having lots of time to explore things with actors does. It gives you this choice to be able to tune it in a way that could go either way, and either one of them could be in the movie.

I've got a question from a Wes Anderson fan: There seemed to be more use of long pregnant pauses in this film. How do you get a feel for the timing of those scenes? I feel like editing for Wes could either be fun, collaborative, or stressfully micromanaged.Pilling: It's all of those things. It's Dickensian, it's the best of times and the worst of times. No, it's purely the best of times. I hope I'm involved in all of Wes's films. We do have air in this movie.

I love it. I was thinking of the line that's in a lot of the trailers where Scarlet Johansen's character says, “Can I tell you about a nude scene?” Then he just sits there and then all of a sudden Jason says, “Oh, did I not speak.” How long do you hold on a line like that?

Pilling: That's a classic comedic pause. I think there's a larger thing at play though spotted by the Wes Anderson fan - very smartly - because we didn't put the movie together like that. We approached it like we've done previously.

Andy has done this for many years with Wes. We also did it with Grand Budapest Hotel, which is it’s fast dialogue, and lots of people talking over each other. We still have lots of that in there – the choreography of where the words land when there’s three different people speaking at the same time is also pretty wonderful.

When we watched it, it was just breathless. I think the initial opening of the movie - which is beautifully languid and really sets the scene for where you are – it went too quickly. There’s no doubt about that. We methodically then went and said, “Look, let’s not be afraid of the desert wind.”

There’s another scene where Clifford is daring to climb the cactus out there and it’s his fifth ridiculous dare, and his dad J.J. pauses for an inordinate amount of time and eventually says, “What does it mean?” We stretched that as far as we had in the footage.

We started to trust the material more. We trusted the location and the setup a bit more. We didn’t need to constantly bombard with dialogue, and in actual fact that wasn’t helping the story settle. I think also, because we’re bouncing between the two narratives, it’s good that we feel like we are back again in Asteroid City in the desert. We feel the wind, hear the insects, and just settle again before we start. There’s also the odd time when you think they’re waiting for their cue, which works for the narrative structure.

I don’t know how to judge how long the gaps are going to be. There’s no formula to it. Put that one in the autodidactic column. We didn’t manipulate either of those moments. The actors did those. But there are times when we do spin things out longer, make gaps where there weren’t any or snip gaps out. We don’t need them, so we protect the gaps that we really want for comedy or pathos.

It’s interesting because I would guess that’s what would happen. If you’ve got an animatic, you don’t have performance, you don’t have the gorgeous art direction. When you get all that you say, “I want to look at the art direction. I want to see the performance.” That leads to things opening up a bit more.Pilling: When we make the animatic, we’ve all pored over the script. Wes sends me a script. This one more than the other needed more readings for me before I would talk to him about it.

By the time the animatics are there and we’re ready to shoot the thing, everybody knows it intimately. So we know the script, we know the story, and you forget that a fresh pair of eyes is not going to receive it as well, because they still have that working out period to do that we all did months ago.

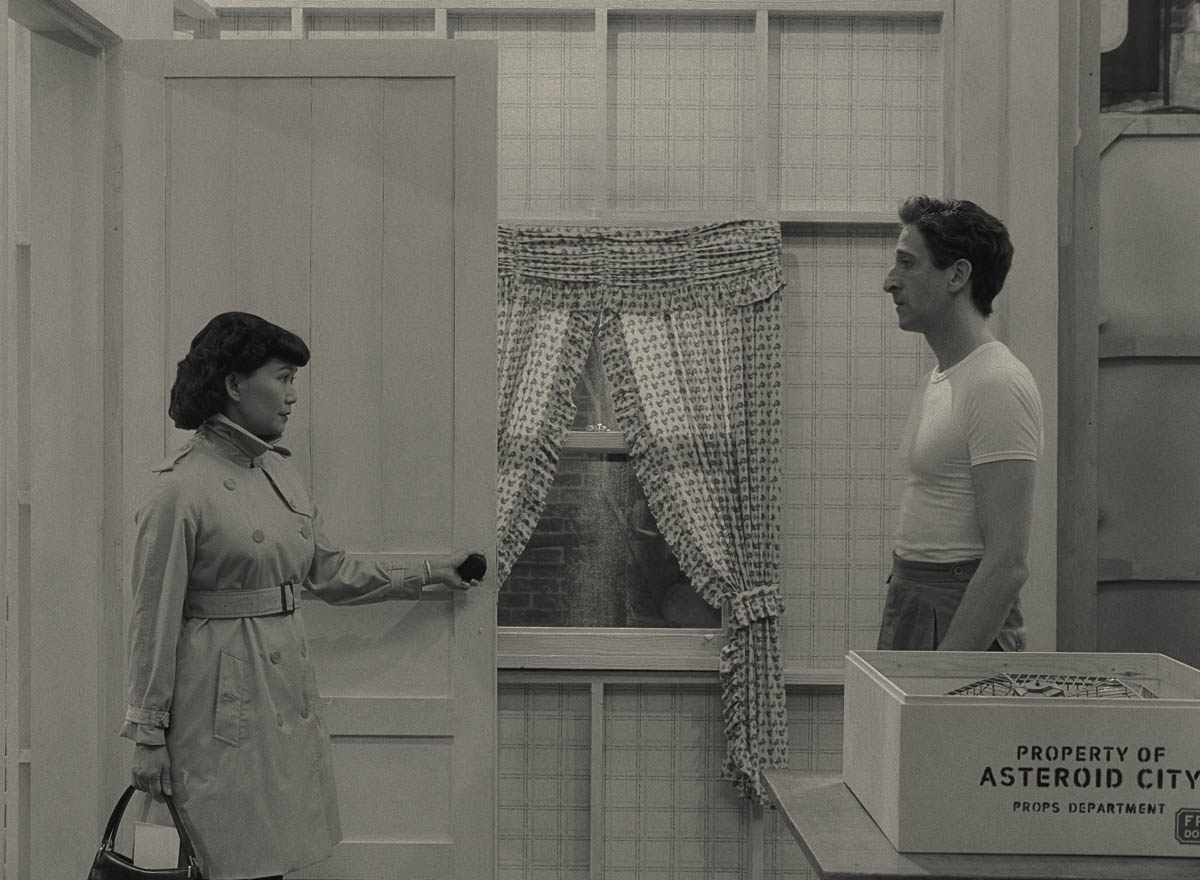

Let’s talk about the scene with Margot Robbie at the end, where she plays this actress who was supposed to be the wife, but who got cut from the film. She does this entire monologue where she speaks both parts of both characters' roles. Talk to me about editing that scene, because it seemed very complex.

Pilling: In truth, it was the opposite. Watch it again. Every time she’s speaking lines that Augie says, we’re on Augie. Every time she’s speaking lines that she says, we’re on her.

The bigger experiment we did was with the four different shot sizes we had – the wide, the closer side shots, and then two closer versions from the front. The trickier job was figuring out emotionally, where do we go in and where do we save the stunning close-up shot? Do we go on in on this line? Is that the emotional point? What’s the best emotional ramp to get us to those closer shots at the end? That was more difficult to work out.

Actually I might have been thinking about the size thing, with it’s complexity as you are looking at a very wide shot where they’re on each side of the screen – almost off to the sides – and then you’ve got closer shots and front close ups. I’m interested in how you determined which coverage to be in.Pilling: It goes back to making sure that we don’t tip the needle to 11, because on the page when you see that scene and hear the words, it’s beautiful. It’s just beautifully mournfully real emotional dialogue between someone who’s going to lose their partner and what that partner’s telling them they’re going to have to do for the future when they’re gone. It’s not that Wes deliberately tries to underplay or undercut, but if we just fired up the violins and went to the close shot on the lines where they’re saying those beautiful words, then it pushes it into over sentimentality.

Melodrama.Pilling: We’re allergic to that. There’s a place for it, but just not in these movies. Wes is a film historian and an excellent one, and has a very deep knowledge of film history and the classics. He really wants to preserve the power of the closeup.

Even how the scene is written, that she’s a maid-in-waiting in a play across the way. This is actually the most important bit of dialogue in the film. It’s the one that touches on grief closest. It’s the one that explains the tragedy and the personal angles of the story, which is the main story in the movie for Augie and his children. Not only did she not make the final movie, she got cut from the final play. So right from the concept stage, we’re underplaying the sentimentality of it, and I think that’s so brave and so beautiful.

You've edited for other directors. How is collaborating with Wes different than any of the other directors?Pilling: It’s a whole spectrum. I’ve worked with directors that are similar to Wes and directors that are very different to Wes. You can see from his films that his approach to making a movie is totally unique. There’s nobody close to him, but the pointillistic approach of every syllable, every corner of the frame, every word, everything is valuable. We must gather everything. We must then consider everything visually and aurally. That’s one thing I really appreciate about Wes, he’s a strong captain.

Once we’ve done a scene, it stays done. There’s no second guessing. It’s an exhaustive intense process to get to where we get to with each scene. But once it’s done we’re just super condiment that’s how the scene is now. That lives on its own. It can be left to do that. We shift things around – like I said – and we’ve moved bits around here and there. But fundamentally I can show you a scene we put together when we were filming in Chinchón – while he was still directing, shooting, and dealing with a mega-cast – that hasn’t changed a single frame right up until the film’s release. It's the precision and the confidence in knowing that once we’ve been precise and done the process, that’s right. It’s correct.

Now there are other directors I’ve worked with very similar traits, they’re very keen to rinse everything out of it and check every vocal performance – “No that syllable’s a bit lost, let’s file through and get a better one,” or “The inflection goes up that’s not as funny, what if we go down?” It’s that sort of pointillistic approach that I’ve seen before in others, but never as powerfully and as confidently as with Wes.

Before I let you go, you're working on the next film already with Wes, aren't you?Pilling: I’m not working on it already, but the animatic is living and breathing. I’ve seen bits of it. I’ve read the script. We’re going to do it. It’s happening. In that sense, my wish has come true – I get to do another Wes movie straight away.

Fantastic. Thank you, Barney very much for your time and for this fascinating look into this film.Pilling: You're most welcome, Steve.