Barbie

In an interesting bit of trivia, another apprentice editor under Naomi Geraghty was none other than Jennifer Lame who edited the other major film opening in theaters the same weekend as Barbie - Oppenheimer.

Today we’re talking with some of the editing team from the biggest pinkest movie to hit screens in a while - Barbie. With us for this conversation are editor Nick Houy, ACE… his first assistant editor, Nick Ramirez, apprentice editor, Maya Rivera, and post PA, Abdul Ndadi.

Nick Houy has been on Art of the Cut before for director Greta Gerwig’s Little Women.

Nick started out as an apprentice to Naomi Geraghty. And in 2012 moved to the editor’s chair where he was an additional editor on Girl Most Likely, and edited Fairhaven, and Manhattan Romance before joining forces with Greta Gerwig for her breakout film, Lady Bird.

In an interesting bit of trivia, another apprentice editor under Naomi Geraghty was none other than Jennifer Lame who edited the other major film opening in theaters the same weekend as Barbie - Oppenheimer.

First Assistant Nick Ramirez was an editor on the documentary Stutz - co-edited with Nick Houy… He also edited the feature film Mayday and was the first assistant on Little Women and Lady Bird.

As an apprentice editor, this was really Maya Rivera’s first film in post. She also was an apprentice on The Beanie Bubble, which is out now as well!

Abdul Ndadi is the Post PA on Barbie after moving over from animation. He did animation for a documentary called Stickman: The Roosevelt Wilkerson Story.

Art of the Cut: Barbie

Nick, the last time we spoke, was when you cut Little Women for [director] Greta [Gerwig] and that is a very different film on so many levels than this one. You also edited Lady Bird for her. Was there a change in the way that the two of you approached this film?HOUY: There were just more babies this time. Greta had another baby on this one, and she had her toddler, whereas we only had one on Little Women. On Lady Bird it was much more simple. And I had a little kid, then, but none of the rest of us did at the time.

You mentioned that you did scene cards on a wall for that film, but only because it was a specific type of film. You don't usually do that. What about Barbie?HOUY: It’s funny. I say we don't usually do that, then I keep ending up doing it, because it is helpful to just look at how things are flowing. I wouldn't say I look at it even once a week, but occasionally I sit there and I really do look at them. Abdul [the post PA] was great about breaking scenes into smaller chunks, so if there was a sequence where we were moving a piece of it around or something, he would make two or three cards out of what was originally one card.

So we were constantly moving things around and trying things out and if we lost something, I would just put it in the corner of the bulletin board. By the end it was like a deck of cards. Part of that was 'cause we were breaking up scenes into a lot of pieces and then losing them. It was also 'cause we were whittling down something that was originally quite long with eight reels into something that was quite short… though still with eight reels. We kept the eight reel form, which was wonderful actually 'cause reel seven was such a wonderful thing. You could watch it on its own as a short: from the beginning of the Matchbox 20 song to the end of the “I'm Just Ken” Song. It was a great reel.

That brings up an interesting point of why would you keep the reels intact? I'm assuming that they were 20 minute reels and then you cut them to 10 minute reels or something?HOUY: More like 25 to 15, I would say. Ramirez can speak to it better.

RAMIREZ: I'm glad the eight reels worked out. There's a small part of me that has some shame as that we didn't get it down to six. 'cause we actually really wanted to. Warner Brothers did have certain reel length limits that they wanted to keep. So months out, while we were still very heavily in the edit, it needed to be eight reels and it was trying to project where that was gonna land.

So eight was safe at the time. We also were trying to account for additional photography and we couldn't really tell how much longer that was going to make it. When we finally got down to time, we thought, “We can rebalance to six.” I had a whole two hour meeting with our sound designer Ai-Ling Lee, who was awesome.

We looked at every possible reel break, and because the rebalance was gonna be just so intensive for the sound team where we were at in the process, we decided to just stick with eight. It was the cleaner, more efficient thing, even though it was more reels than most people are used to, ao we did have some short reels in there. But in the big picture, it actually saved everyone a lot of work. We needed every hour we could get in the last push of this film.

Most of our audience is going to know what it means to rebalance the reels and why you do it, but can you explain what that process of rebalancing is like and why do you do it? What does it mean to rebalance reels?

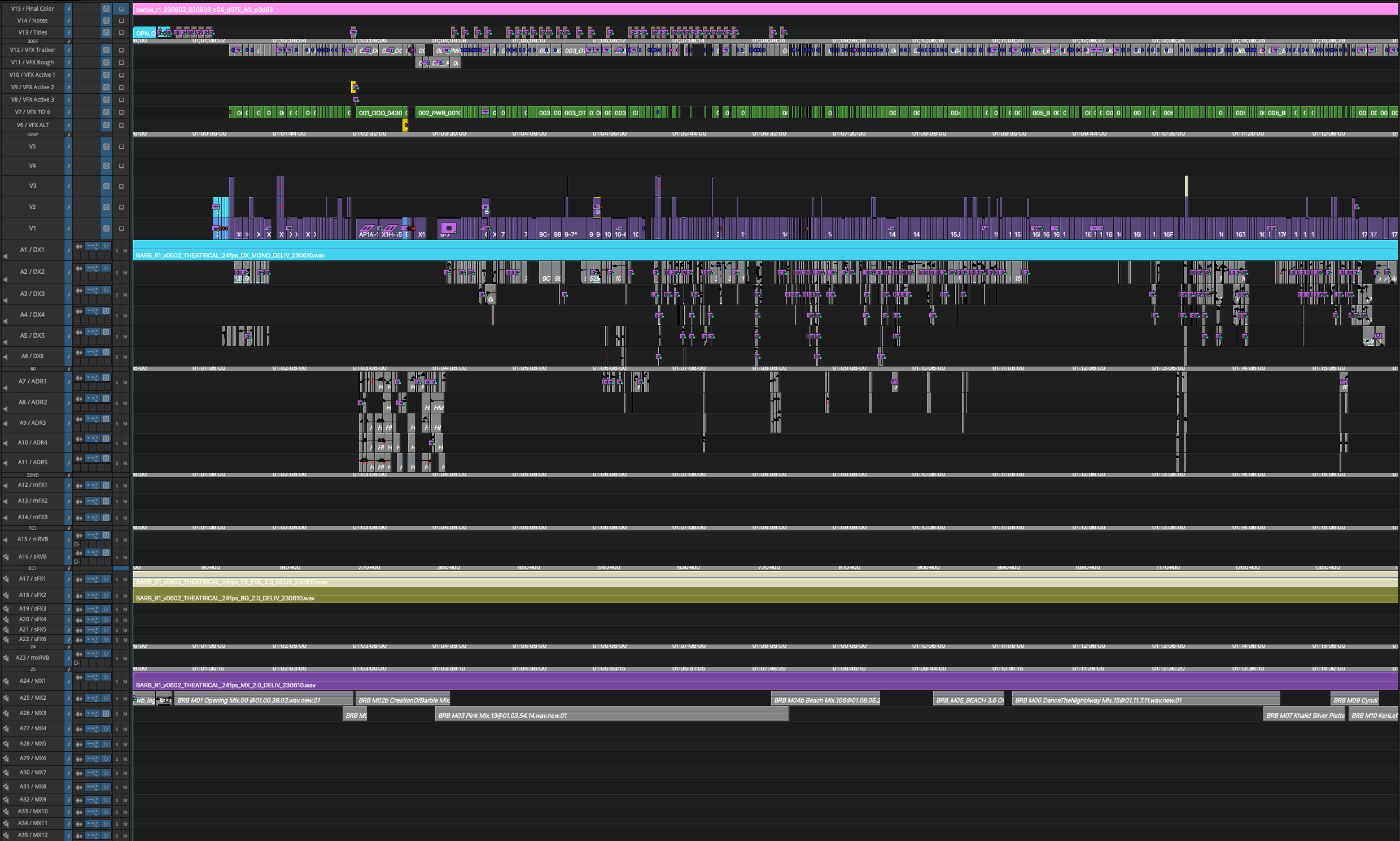

Avid screenshot of Reel 1 of Barbie. Full breakdown below.

RAMIREZ: Rebalancing the reels. Trying to put that concisely really is just finding the break points of segments of the film that we work in, which these days primarily I feel like is just helpful for organizational and workflow processes, particularly at the mix and the DI because you work in your stages of reels: Reel one. All right.

Now we'll go back and do notes. Then we'll move to reel two. We were at eight reels early on in the process 'cause we needed to be, but now that the lengths have changed, let's take a look at slimming it down to only six, which is usually, I feel like a lot of people get into that range if they can. You want a break where there's a natural point in the story if you can, so obviously not mid-scene or mid-feeling but also on a technical level that there's hopefully not music crossing over the scenes.

That's always a bit of a challenge to join those reels when there's music crossing over or even overly-detailed sound work. That was the big driving force of why we didn't get it to six reels. We just decided not to force everyone to go through a rebalance 'cause that was actually going to be a pretty time consuming thing. I didn't want to just demand, “Everyone, we're gonna have six reels” and now the whole FX team and sound and everyone has to take however many days to get that all sorted out.

How long was that editor's cut?HOUY: What do you mean? The assembly? Greta and I - we're always looking at scenes while she's shooting, so we don't really sit down and just do an assembly. I do it with every other director. She's one of those directors - and she does it so well - where we play the first assembly scene and then cut the scene and then go on to the next one. Even if she's tired she's in there the day after shooting. She's just a beast. She really works super hard.

I love having a couple weeks to make my assembly perfect, but honestly, I work so hard during the dailies process. I have an assembly the day after shooting that I think you could screen. That's my goal: a screenable, playable movie the day after the shoot ends, which I know sounds insane and impossible, but that is really what I try to do, so wherever she wants to go, we can look at the scene and work on it together right away and we have a good version of it.

But we don't just sit down and watch the assembly. Whereas I would do that with most directors. She really wants to go through, watch a scene, cut the scene, watch the next scene, cut the scene, go through the whole thing, and then we watch the whole movie.

I've heard that same thing from other editors and directors that it's just too painful to watch something that's that fat.HOUY: It's not so much that it's painful, it's that it's not helpful. It's actually better to go through it - make sure that you're using your preferred takes and actually reviewing them sometimes just to make sure they're your preferred takes, because on the shooting day it's very different than when you're actually sitting in the room watching it as an audience and making sure you're understanding what footage you have to make the scene work properly, because you've been so busy on set, so you actually have to just let yourself go through that process a bit before you can look at the whole picture. “Let me just get my hands dirty in each scene before I watch an assembly.”

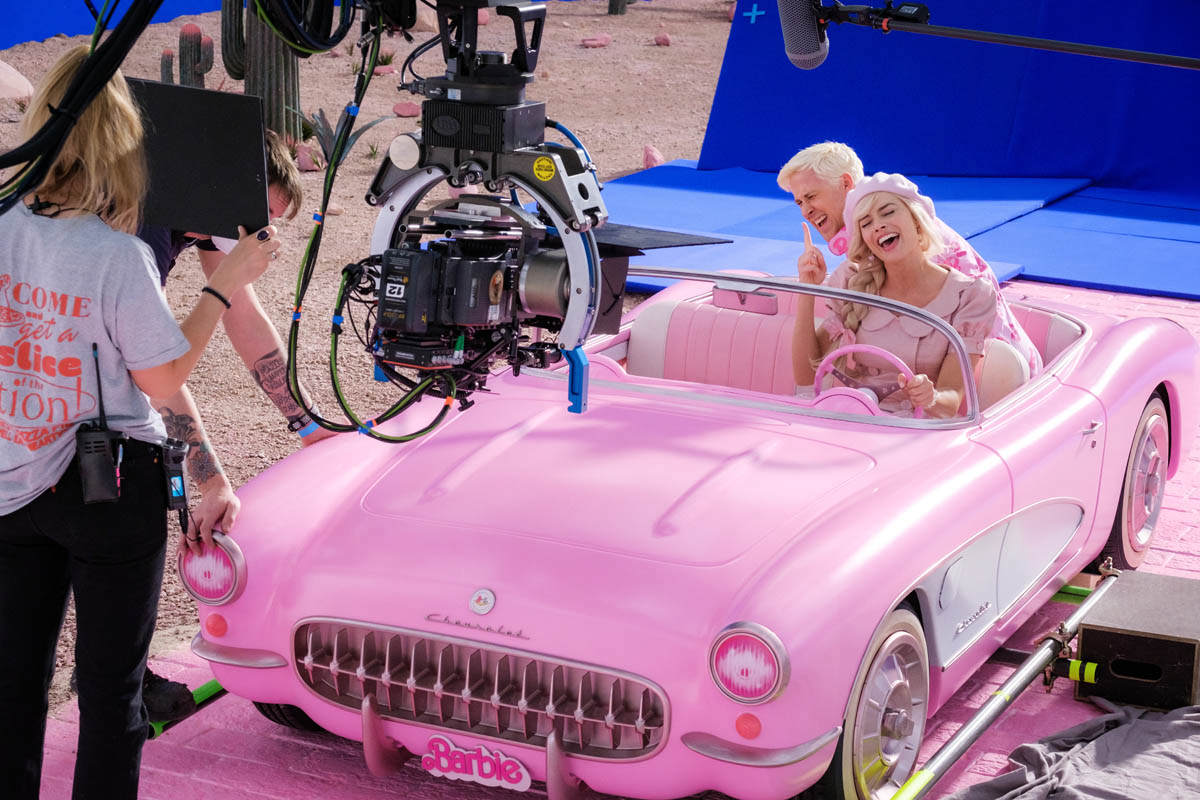

HOUY: Yeah, we actually brought in the original version and we actually have the real scanned shots from Kubrick's 2001 as the opening shots of Barbie. We actually had to have them find them in the vault and re scan them and then we recolor timed them. And then the way Rodrigo shot that sequence, obviously he was referencing everything about the way that Kubrick had done it.

And that's a fascinating sequence to just study and see how he had shot it over years, I think. Each piece was from vastly different times. And just the way he did the backgrounds and things was kind of revolutionary. When we brought it in and kind of tried to do it shot for shot, obviously it was a bit too slow, but the main thing that I wanted to do was hit the music at the same time when the ape smashes the skeleton with the bone the first time.

It hits at a very particular music note. And so I made sure that the girl smashing the doll hit at that same exact moment the first time she smashes the doll. I thought that was just the most important moment. We tried to match it up, shot for shot, and then we just sort of sped it up and made sure that that first bone smash was timed with the first doll smash. And I could go on and on about what that scene means both in 2001 and what it means in this context, which I think both are extremely meaningful to human existence and to women and to what we're all doing today.

This seems like a very LA movie, but did you cut this in New York?

Editor Nick Houy, ACE

HOUY: Oh, yeah. And 90% of it was shot in London. So it's a very London movie in my mind, but a fair amount was shot in LA and then the whole post thing we did in New York - even the mix and the DI, though we had a lot of LA people come work on it, but the actual editorial and VFX editing crew was all New York-based. And then the VFX supervisor and coordinator were from London and our sound people were from LA. Our colorist was also from LA.

How did that hyper-stylized performance of Barbie affect your editing?HOUY: No matter what, you're just trying to tell a story that's personal and meaningful to you, and it should make you laugh and it should make you emotional. So that's all we were doing. It's just that it is a different tone. So you are having to find that tone, and that's tricky.

When something's heightened, it's so easy to go into camp or have it hit you over the head with a hammer - which there were certain versions of certain scenes and the whole movie that were too fast and too broad and too campy, and we were constantly just trying to walk that fine line of making it feel very real, but also heightened.

If you see each take and you actually see the nuance in performance and start to sculpt that, it's drastically different. It's really amazing what you can do with just hitting a handful of scenes like, “This pass let’s make Ken a little less extreme. How that would change the whole arc of the movie?”

I was thinking of the big changes in tone. How did you sculpt being in one tone, being in another tone, and those transitions between tones?

HOUY: One thing I really enjoyed doing is switching tones in transitions. I find that extremely satisfying. As a filmmaker and editor, one of the things I live for is doing those kinds of shifts properly.

First of all, giving it the attention it deserves and understanding what you're trying to do and really giving it that time and finding the right sound design to do it, the right visuals to do it obviously, and the right music to do it, and the right emotional backbone that allows you to get there throughout.

It has to be there throughout, or else you're not gonna sell it. It's very specific, so it's hard to speak generally about it except, the movie's always trying to tell you what it is and you need to let it go there and you need to give it the space to do that and it either works or it doesn't. Sometimes it takes a few screenings to suss it out, but you really have to just keep working it.

I feel like the pace of this one more than anything we've worked on in the past was particularly tight. Keeping that up was a big part of being nimble to switch tones so swiftly because there is so much happening that if it ever dragged for a moment too long it would start to not flow.

Greta always says that it's like singing a song and you just have to find the rhythm and that there's a place where it needs to go to the bridge or whatever. You can push the analogy as far as you want.

I can feel it, especially when I'm watching it with a small audience or a large audience that we're offbeat now, and that's the best way to say it. You're singing along with it and then suddenly you're offbeat in some way. Whether it's too slow or too fast, it's very common that we've done something too fast and we need a moment to breathe. We found that in a lot of places.

Director Greta Gerwig

I would also say, “When in doubt, tightening can help you pull off things that you wouldn't be able to pull off if you were more languid.”

Maya, what was the post crew experience like for you? You’re on this call with a lot of guys.RIVERA: There were a lot of women on the crew, actually, I shared a room with Gloria [Tello], who is a great assistant editor. I haven’t been in many editing rooms, but the ones that I've been in have been very mixed company - like men and women.

People like you and Nick Ramirez and Abdul are really probably the very first screening audience for stuff that Nick Houy cuts. Can you talk about your experience in being able to see early edits and speak into them and how did you feel about giving your opinion?RIVERA: The way Houy works is that he really delegates ideas to the rest of the team. So Ramirez, I, Gloria, we would take things that Nick or Greta threw at Nick, and then we would just go with it and play with our own ideas and see if they stuck. And some of 'em did.

HOUY: When I think about when I was an apprentice, my most exciting moments were when. Naomi or whoever was my editor, would come in and say “Hey, we're working on this crash sequence. Can you just try a bunch of different ways of doing it and try a bunch of different sound design things?” So I tried to do that as well. And obviously there's a million other things going on, but if you can get to this, it's the most fun thing to do, obviously - just be creative and it makes the movie better.

There's so many great creative things that Maya did that are in the movie and it's the biggest comedy opening of all time or something. Maya, you had one of the funniest jokes in it and you cut that in as an apprentice. It's amazing.

Maya! So cool. What did you cut?RIVERA: I added a jump scare on top of Kate McKinnon's face. That's something I came up on the fly - grabbing inspiration from Pee Wee's Big Adventure and TikTok.

Nick Ramirez. Before we started the podcast, you and I talked about this idea that Greta has this relentless pursuit of the right idea and that you'd often go fourth, fifth, sixth idea before you got to the best or final one.RAMIREZ: Going back to Lady Bird, Nick and Greta collectively have always fostered not only that relentless pursuit, but the team around that to make that happen. Especially with something this large, there are more ideas than there is time, so it would just be a constant running list of “try this” or “try that” and we would jump in where we could find some time to do that. Honestly, thinking back to Lady Bird, that was maybe only my second assistant job ever.

One of the first things I realized working with Houy and Greta is the degree to which you just keep trying - keep chasing the idea - making sure it's the best it can be. Or pushing it beyond the best it can be to realize, “Oh, we broke it. Now we gotta go one version back.”

That sort of mentality, while difficult sometimes could be really exhausting. Also it can almost become circular when you've done versions and think, “Oh wait. We did that one before.” So that's just like a general environment.

The standard working with Greta and with Houy is this team aspect of: If you have an idea go for it. If you wanted to try something, do it on the side, throw a bin up top and put a note on it and we'll check it out later. So it's a great learning environment and teamwork environment.

I don't know if we want to get into it right now, but a good example of that was the “human montage.” That was probably the biggest because it was such an innately collaborative thing because it is material made from the whole crew and from the cast and it actually took everyone's heart and hands to get that shaped over time.

Nick Houy, can you explain a little bit about what this “human montage” was and how did it work?

HOUY: In the script, it was a Malick-y thing - like a Terrence Malick thing - that just showed life. We never shot anything for it. We didn't really know if we needed it. And as we were screening the movie for small groups and for Warner Brothers and different people, we felt we did need something there, and so we tried the “Godfrey Reggio version” and the “Terrence Malick version” and the ”Stan Brakhage version” using either found footage or nature footage or all these things - like timelapses of a flower coming out of the ground.

We tried Man with a Movie Camera vibes [1929, Dziga Vertov]. We did all these different ideas and we ended up with personal Super-8 movies. Ramirez's aunt is in it as this beautiful piece of film that's almost breaking. It's like the memories of women and their mothers before them, and their daughters. It's echoing what Rhea Perlman says in the scene in a visual, visceral way. And once we found that, I think it just came together and it was beautiful how everyone found their footage of people in their lives - friends, family that they wanted to use in the movie - which I think was really beautiful. It’s another way that we really made it our own. It was a personal film in a lot of ways.

Maya, did you get to contribute to that?RIVERA: Yeah. My great grandmother is in that montage and Nick Ramirez, and Gloria and I did our own versions of it - several versions of this montage trying things out. That's ultimately what stuck.

Abdul, did you get any of your family members in there?NDADI: Oh yeah, it was really amazing. My mom, who had, passed away last year she was in it and my niece. Actually I just got video of my aunt’s reaction to seeing it in the theater. It was really touching actually.

And Nick Ramirez?RAMIREZ: Yeah. Two shots in there that are the same person: my Aunt Sue back in Arizona, but at two different ages. Her as a teenager and a young girl. Very beautiful shots that my grandpa had filmed way-back-when on 8mm.

Also a shot of my grandma who I grew up with - Grandma Connie - she made it in. All of us did multiple versions and variations of ideas to figure what created the right feeling and dozens of variations using different types of material and structure to get that to that point. Shout out to, not only to Gloria Tello but Jaime Sukonnik - another assistant editor who came on for the last push of the film with us.

I remember her first week or two on getting up to speed. She was bringing in a ton of footage of her family who wound up in it. She also was a big part of getting that ball rolling 'cause we didn't have the montage in the whole time. So when we recommitted back to the idea, we had a little bit of a ticking. So it took the village.

Nick Houy, was there direction from Greta about what she thought that should montage should be?

HOUY: From the first time we talked about it, it was just something Malick-y that represented life. It was very broad. Greta and Noah are so smart and they're so in tune with what they want, but the specifics are always things we have to throw at the wall and see what sticks.

So we just made a bunch of versions and said, “I like that shot. I don't like that, blah, blah, blah.” Until you finally get to something where we all agreed it was very meaningful.

This is not even to talk about sound design and music yet, which are so integral to the sequence, but just getting the images right and deciding that it should be all from people who worked on the movie, which of course - once you see it from now, 20/20 hindsight - it's so obvious.

It needed to be only women and it needed to be from people working on the film. That's what makes it special and beautiful and unique, and tell the story. But it took us a while to figure it out. That's what's funny about things like this is it seems so obvious now, but when all you have is a blank page, it takes you a while to get to it.

On top of that, Billie Eilish just sends us this unbelievably beautiful song and we all were crying, listening to it. It was unbelievable. The lyrics and everything - she was just so spot on with it. So we thought, “Okay, we also have to use that in the sequence.” And Ai Ling's sound design was beautiful. And Dan, who also was the sound designer on it, did a lot of work on that sequence and was fantastic.

Talk to me about the sound design for that sequence.

HOUY: We ended up bringing it down quite a bit in the mix. Ramirez, you probably made the first architecture of these deep sounds. 'cause we would have Super8 footage that was textural building transitions between these shots that are celluloid memories, so the sound would also feel like a memory. It was whooshes, rumbles, driving sounds, things like that. Also occasionally hearing the person on-screen doing a little noise. At one point Greta is jumping off a bridge in Sweden or Denmark and hitting, and so we hear the splash, but not doing it every time. We had fireworks also. It was just creating a beautiful kind of cacophony of abstract sounds that accentuated it. You feel them, you don't hear them, if that makes sense. Of course the music ended up being forefront. It wasn't always, and I think that was the right decision.

I wanted to ask about pacing. One of the scenes that I remembered being rapid fire - having a great rhythm to it - was when Ken decides he wants to perform an appendectomy.HOUY: That's one of my favorite. I love cutting things like that. That's Greta too. If you think about the scene in Little Women when they're all talking and it's Christmas morning and there’s this amazing Steadicam shot. Getting that rhythm to fire as quickly and beautifully as possible and in the right sequence.

So that's a perfect example of it as well. No matter how it's performed, you have to make it stay at the right tempo. That's the most fun part of editing: taking multiple performances at different speeds and different interpretations and different timing and everything, and putting it in the order you want it in at the tempo you want it in and with the performances you want, and that can involve swapping audio takes or syllables.

It can involve cutting the middle out of words, which I do all the time. As an editor, that's your job: to manipulate the footage. Push it to its highest degree. Even if you have the greatest actor, you have to cut that perfectly and you have to push it as far as you can push it. That's your job, just like it's his job to do the best acting performance.

When you have these insanely great performances and it's beautifully shot by Rodrigo Prieto, and the greatest production design you've ever seen. All of it firing on all the cylinders. Your duty is to push it. So that's an example of a scene where we just pushed it, and we found that one really early on. That's the rhythm. That's the funniest way to do it, and that actually stuck for a lot for the rest of the movie. There are some scenes where the first time we did it, we nailed it. Then there are other ones where it just takes a long time to find it.

Before we move on to some of the other folks on the call, I wanted to talk to you about documentary. You and I have both edited documentary - and both directed documentary. How does that speak into your work or how does it help or inform your narrative scripted stuff?HOUY: Nick Ramirez can speak to this because we did a documentary together right before Barbie, it was called Stutz. We co-edited it. I would say the main thing is: it is no different. That's an important thing to understand, is that you should also approach a scripted narrative as a documentary in a way.

Everything that you can use, you should use it to the best of its ability. Don't be boxed in by the script or by the footage in any way. That's what documentaries do. You're using everything that you can to tell the story. I think that's the key: to have that same approach with a scripted narrative.

If you have a shot of something, it doesn't matter if you're using it in scene 93, you should use it in scene three. See how it works there. You should use a piece of it and cut it out and put it behind somebody in scene 52, you just have to use everything that you have to try to tell the story as best you can. That's what I feel like you do in a documentary inherently, and sometimes people have trouble doing with a scripted narrative.

HOUY: Absolutely. A lot of the great editors that I look up to, they always say once you feel like you have the movie, perfect and your audiences are loving it, that's when you need to go back and watch all the dailies again and comb through it all again. You're gonna see things completely differently.

Because you now have the context.HOUY: Yeah. And then you'll find these little gems and things that you need to work into it and try it out and show it again. That's how you get to from 90 to 95.

Maya, was that jump scare something you remembered from some place that was not meant to be used?RIVERA: Absolutely. The shot was used, but we only see it for two seconds in a totally different scene.

So as an apprentice editor, when you were watching Nick or seeing all of this, were you astounded at how many revisions and how much it evolved?

RIVERA: Absolutely. So many things have been tried. The assembly cut is like totally different from what we have now. It's amazing to see the journey this movie went through. I remember watching it with Gloria and thinking oh, this movie plays like an indie movie a little bit. Now it’s turned into this grandiose, sensory overload thing, which is amazing.

Nick Ramirez, do you have thoughts on the evolution of the film and how much it's changed?RAMIREZ: I do wanna jump in on the indie spirit idea that Maya mentioned. From the get-go for me, it was such an interesting thing, because even Little Women was not really an indie, though it very much had that heart. Lady Bird was obviously an independent project and that feels like so much what Greta and also Noah has as being in their wheelhouse.

So to step into the arena that is Barbie, but coming from that place, was such an interesting thing because inherently baked into script I think a lot of people seem to be responding so well to, as the film does it all. It is this high octane, comedic, music-driven, pink, bedazzled parade that also has you crying at this human montage in the last moments. It's incredible, and I don't think that would've been possible without that independent spirit underneath.

She's not missing or losing something along the way. And if there's any movie that you could lose it in, it would be this one. There's so much going on as it evolved. That thread was always in there and needed to be taken care of. And I guess from the evolution, with this caliber of actors, some of the stuff that was in the dailies, whether it was just little improvs, there were so many amazing variations that could be done.

I feel like it's almost like there were pieces of candy at every turn where you think, “Oh, that's so funny. I want to keep it in.” It took a real discipline to not be taken off track by that. I can say for myself, I can think of so many specific takes or variations early on where - still to this day – I think they were hilarious.

And when they maybe got shaved down or reoriented, there's a little bit of me that thinks, “Oh I miss that!” But I know that’s the process. It's so hard to lose things that you love and that's just so much of the job. There are at least seven versions of this movie that we have screened or worked on that I wish people could see 'cause they're amazing in their own right.

And we just ended up at this one, which I think is the best. We just had so much great material to work with. Abdul was there the whole time as well helping to do a lot of the visual effects and things that we were temping - just trying a bunch of crazy ideas with horses and spaceships and the depth of the Mattel universe of toys to mess with was so deep.

He was really going through the Mattel archives and finding all the best things to put into the movie along with the VFX department and the design team.

Abdul, what did you get to mess with? I know that you've got a little bit of an animation background that we talked about. What did you get to do?NDADI: It was always a collaborative effort. Nick and everyone always included me, which was pretty awesome. I got to mess around in Photoshop and do some designs for that Mount Horsemore [the Mount Rushmore send-up]. Different things here and there to help whatever shots needed temp VFX things. I was always happy to help.

HOUY: There's a shot early on where it's two Barbie astronauts saying hi to Barbie when she's driving through the town. Abdul suggested, “Let's put this little crazy Barbie spaceship in that I found.” It was a real spaceship from the Barbie world. There are so many things they've made and that's still sitting there exactly the way that he wanted to put it in. You were doing that early on and there it is in the final movie.

NDADI: We also got to do a lot of like temp ADR, too. That was also lots of fun, just playing around with different sound things.

RAMIREZ: Yeah, we did a lot of ADR in this movie. We should have Brian Bowles, 'cause he is our amazing dialogue editor. We had the most ADR probably of any movie that's not an animated movie, I would say. We ended up using 5 to 10% of it, but we tried so many ideas and did so many things with ADR It was really fun and Abdul was amazing at it. As was our whole crew actually. We had a good team of actors on this post crew.

Abdul, we were talking about how you just got out of school, and the things that they don't teach you - like the fact that most of your life is gonna be freelance and nobody even talks about that. Can you tell us a little bit about the idea that this is not what I thought my life maybe was gonna be, but it seems cool?NDADI: Yeah, it was interesting, going to art school. I went for animation. I think the whole four years I was there the only time I heard the word freelance was maybe once. It wasn't even explained what being a freelancer was until like I hit the real world and it was just like, holy moly. The whole storm of, “Okay, you have a gig, you don't have a gig, what are you gonna do?” It was really tough trying to navigate that, but thankfully, once I decided I wanted to switch from animation to live action, I joined the Made in New York Post-production program, and that's how I met Maya. We have a little Slack group. She said, “We're looking for post PA for a film. I didn't know what film it was at the time, I sent my resume Maya's way, and after I met Nick Houy, I got to join this awesome adventure - meet the amazing crew, and it's been pretty awesome.

Talk about how important connections are. If you were gonna talk to a another young editor what advice would you give them?NDADI: Networking is paramount. When it comes to networking a lot of people think it's about “Who's the biggest person that could get me the most jobs?” but you don’t have to go meet Christopher Nolan or something. It's not that. Look at your peers. You know what I mean?

One of the mantras I love the most is from Joseph Campbell. He likes to say, “Follow your bliss.” My bliss is storytelling and film. So, when you're following your bliss you meet all these great people that are following their own bliss - following their dreams, and when those things happen, it's like all those connections you make… Like Maya.

I meet Maya, we both are interested in the same things. That's the connection right there. She got the gig and helped me with it and I'll hopefully be able to help her or someone else with it. So it's all about genuine connection. Not really about, “Oh, this person should be a rung on your ladder to get to where you're trying to go.” It's about being personal and just bonding with people. That's what it's really about. So it's networking, but it's really about connection.

Amen. I love that idea that networking is not like LinkedIn. It's a personal connection you have with other people. Nick, is nodding his head. I also love the fact that you pointed out that Abdul didn't have to know Greta Gerwig. He knew Maya.HOUY: Exactly. When I was an apprentice and PA-ing, that's what it's all about. It’s like you and your peers, just trying to help each other out and make things happen and if you're all doing that… like Jen Lame and I were doing… we were apprentices together and now we have Barbie and Oppenheimer quote unquote “against each other.” It’s cool to just pursue what you wanna do and “follow your bliss,” as Abdul said. And if you keep doing it with the right people and your heart’s in the right place and you work hard, you'll achieve at least some of that for sure.

Tell me about meeting Abdul. What did you find in him that you thought was great, because he doesn't have a ton of experience as an editor -which you wouldn't necessarily expect for his job. What was it that made you feel like he should be on the team, or even Maya, or Nick Ramirez, for that matter?HOUY: I always say that I just look for somebody who really wants to be there and wants to be creative and is excited to be there every day and is a good communicator. I think that's totally important because if you're working really hard with a team of people and one of them can't communicate properly, everything's gonna fall apart. Abdul is a great communicator. He says, “Hey, I have to leave at three o'clock to go see my nephew's soccer practice.”

We all have to be able to say those sorts of things and work really hard and kill ourselves over the material, but love doing it. And I think that's key: actually wanting to do it and enjoying doing it and being able to communicate that you also need a life outside of that. And just being able to say it organically and all work together to the best of your abilities.

You can just tell when people are gonna be like that and when they're gonna be holding something in and being resentful in some way, or not communicating what they need, which is super important. You have to be able to communicate what you need or else people aren't gonna be able to anticipate it.

Maya, thoughts on this?RIVERA: One thing about this crew that I really appreciate: this crew really sees your personhood. It's not all about work all the time. If you have family things going on, go deal with it. Your humanity is considered, which I really appreciate, and it speaks to the movie too. It's all about being a person.

RAMIREZ: It did not turn out to be the case, and I think most Firsts in this scope of a film would probably agree. For all of us - I don't wanna speak for everyone here, but I think from, honestly, from Greta on down - none of us have done anything this big before. You have an idea of what this would be, so you're prepared for certain aspects of it in that sense, but surprises still hide around every corner.

Even knowing, “All right, this is gonna be a little crazy some days, but we'll squeeze some time in there to cut.” especially because Nick and I - on a totally different project - had been co-editing. In fact, I was finishing that while we were starting this. There was a lot of crossover actually.

The first four or five months as a First on something of this size. On previous jobs I did everything. I’d cut, I’d do sound, I’d do VFX, I’d do the temps, I’d coordinate workflow - all these things. And that remains true on something this large, but parts of it almost rose to more of a supervisory level that I wasn't fully expecting.

That's not to say we didn't have great post supervision from Jen Lane and Amanda Dudzinski, our coordinator. It was just that there's some nitty gritty things that - with all the departments firing all cylinders - I could easily spend half or more of my days walking down the halls or making phone calls to make sure certain things were in sync or that we were putting our best foot forward for the most efficient unfolding of events, whatever might have been coming up that day or week. One feature to all the experimentation and turning over of stones that we do on this one: It does keep you on your toes. What’d we wind up with? 1300 visual effects shots in the final cut?

HOUY: 1500. Yeah.

RAMIREZ: You're constantly changing things. There's a reaction time to those things, so if I wasn't checking in with VFX, they'd be checking in with me, asking, “Is this sticking? What's going?” There's always a lot of strategizing going on. Crazy organization. So that was new for me - a new challenge and skill to, to further build out.

I would normally do a lot of things on a show myself, but on something this big, I had to delegate. Gloria, Maya, Jamie - when she came on – Abdul, wee needed to split this all up. That was a big part of the job. So that art of delegation and organization was a new step on this one.

And Nick Houy, you didn't have to do a lot of that management because that was on him, or did you feel like there was stuff that you needed to do as well? Or were you just nose-to-the-grindstone?HOUY: That's what's great about Ramirez. And since we are so close - we've worked so much together - I would walk into his room and he would see the look on my face and know exactly what I was gonna say. Because I'm in there with Noah and Greta almost all the time - all day. I always have these tall yellow notepads that I burn through. I'm just constantly making tons of notes, especially after a screening. You're getting it from producers, studio. We have many producers. We have Noah and Greta, and then all the people just in the screenings and stuff. So I've got millions of things to always filter through and being able to have a team where I can quickly communicate and delegate was essential.

We would never have made it if it weren't for Ramirez and the way he was able to delegate to this team. Stellar. It was actually super-human, I would say

Structurally was there any sense of needing to get to a certain point in the film earlier? On films I've cut, it's been: how quickly can we get to act two? Was it: how quickly can we get to LA? How did that evolve?HOUY: The first time I read the script, I said, “Everyone's gonna say she needs to get on the road sooner. And there was that whole scene where she's getting ready to get on the road and the Kens are watching the Barbies. I love that scene 'cause it's such a great gender reversal. It's all about Barbies and what they’re journey is. And the Kens are off on the side, standing by the pool, drinking their little drinks with their fancy straws and they don't really know what the hell they're doing. Early on people said, “You don't need this scene. Just get on the road.”

And sure, that's totally a simple note to give and it makes total sense. But you need that scene, man. It sets everything up in a beautiful way. And even on the page I thought, “We gotta keep this scene.” I think it was like the last thing we shot 'cause they kept thinking it would fall off. So things like that, you think, “Yes, of course you can cut that, but without it, it's not the same movie.”

And there are so many things like that and you need to obviously try a version without it. We've tried millions of versions without it, or much shorter or much longer. There's a lot more to that scene in the original version. So you just have to find the right balance and know that you're not selling the movie short just because of some idea that obviously you need to get things moving at a certain point in the movie. You also need to be flexible and let the movie tell you what it wants to be.

Nick Ramirez mentioned the idea of so many different jokes and ideas and that's one of the things that I thought of as I was watching it is you could have done so many more things, but the movie can only handle so much.HOUY: Oh, and they were in there. For a long time. So many more things.

That makes me think of that classic idea about: art is knowing what's the minimum you can have.HOUY: Yes. That's a really good way to put it.

Otherwise it's baroque, right? It's too much.HOUY: … and sometimes it calls for that. Like the “I’m Just Ken” dance scene is too much and that's the point of it. It's supposed to be. They're taking over the movie and they're ridiculous and they go way too far with it. So as long as you understand what the purpose of the scene is and do everything you can to make it shine as best as it can, whatever that purpose is at that moment to tell the larger story then you're doing the right thing.

I love that idea of purpose. I call it “intent.” What's the intent of this scene? Because if you know what the intent is, then you can properly make decisions like, “We can't cut the ‘Ken at the pool’ scene because that sets up this important idea.” What's the intent of that being in the movie?HOUY: Everything's a setup and a payoff. You have to think of it that way, too. If you have the setup and not the payoff or vice versa, then it just doesn't work.

From an assistant point, Maya, what are some important habits that you think are important to an assistant?RIVERA: I think maybe Ramirez can speak more to that. With Ramirez's leadership and how to organize tracks, how to organize the overall project, that was really key and he really streamlined this project. It was so easy to navigate.

RIVERA: Tons of folders…

In the AVID project?RIVERA: Yes, in the AVID project. Also in the NEXIS [media storage]. Tons of labeling things, where they need to go, what they're for, dating them. Basically creating a library and maintaining it is really important. Following those rules. There's so many other things.

HOUY: I just wanna point out, something because Maya, you killed it. She's an apprentice editor and she was basically, until Brian Bowles - our amazing dialogue and ADR editor – arrived, she was basically the gatekeeper of all of the ADR. We're talking very complicated stuff with lots of temp ADR with huge actors like Helen Mirren and she was the one saying, “Oh, that line's out this line's in. Lemme print out new sheets for that” and she’d hand it to Margot, hand it to Helen Mirren. She was running that amazingly, and she was so organized. On top of it she was creative. She’d say, “Why don't you try this line too?” or “Remember that line from three months ago that Noah recommended? Let's put that in on the list too and see if Helen can do that.”

RAMIREZ: Then, once Brian came on, obviously he took over that and she helped him with it. She had amazing ideas. When you think about how many lines we would temp and the idea of putting them on the list, taking them off…but you do that for six months, and you’ve got quite a list going. This film had such a huge amount of characters, so it was a real process. Maintaining that tracking. Then, once the sound department was up and running, sharing that with them and making sure things were up to speed. Then Brian would make his more refined and beautiful ADR sheets for review, and we'd have to figure out a system for that: “This is the review version.” Then Nick and Greta would call out old things and Maya or Gloria would be on top of it to say, “Wait, what about that line from three months ago? Do we still want that?” It was always a very continuous sort of thing. We always went in, fully armed with the idea kit for each ADR session. Even if the cut changed back to an old version, you had to have that ADR line ready.

RIVERA: Yeah. I didn't expect that feat of organization to be handed to me.

Abdul, what about you? What did you learn about the skill sets that maybe Nick Ramirez and Maya taught you were necessary to be successful?NDADI: It was just super inspiring just to be around all of 'em and to see Nick Ramirez and the way he was organizing things and delegating different things. I was able - especially as the PA - to see how each different thing that was being delegated was serving the whole. It was pretty amazing to see. It’s amazing, especially being on the project for so long to see how everything evolved. It was just pretty wild to just see each and every different compartment and how they were able to just merge this thing.

Nick Ramirez, talking to new assistants on other movies who would probably love to make this jump you made from little indie First to gigantic blockbuster First, what advice do you have for those people?RAMIREZ: Oh, good question. It's all about supervisory skills, I think. For me, that's really what it was. You have to have your compass set - not just a day ahead, a week ahead - maybe more.

HOUY: You always saw a shipwreck coming and warn us, “Hey, if we don't get ahead of this, something bad's gonna happen,” and you would do something about it and that's key.

RAMIREZ: That was the biggest thing because on smaller films - even if you're working incredibly hard - you have a smaller footprint, you're more nimble. If something unexpected comes up or happens, you can absorb it a little more easily than with something to this scope. There was a certain radar I had to develop of looking ahead. So it was constantly looking forward than working backwards from that. Nick Houy – because we’ve worked together for so long and we have a trust – would let me run that aspect of the process, even if it sometimes meant, “Hey, that thing you asked to get done right now? Does it really have to be done right now? Or can we do it tomorrow morning?” Reorganizing some of those things, being able to speak up when there was a need beyond those. It's true on every film, but it's just so much more true with the wider team.

Avid screenshot of Reel 8 of Barbie.

And just communication in whatever form that takes. I would try most days, particularly in our last couple months to huddle in. I'd go into Gloria and Maya's room - which is right next door to mine - and we'd all huddle up and just say, “Here's everything in my brain. What do you guys got? Let's make sure we're in sync.” We would constantly check in.

I also had to make sure I didn't take up too much time doing that, but I needed to communicate so that other people aren't too “blinders up” and just doing their thing to have a broader view so things aren't falling through the cracks.

Everybody needs to have a broad awareness of the wider things going on. Sometimes I’d just share, “Hey, just so you guys know, this is going on with VFX today. You don't have to worry about it, but I'm just letting you know. That way if you are showing Billy Eilish the scene and Matt comes in and has a question, Gloria, I know what you're talking about.”

I want to thank all of you for sharing. I know Nick Ramirez just took a red eye in and he's probably ready to fall asleep. Thank you so much for joining me. Nick Houy, thank you for bringing the team on and letting them share as well.HOUY: Yeah, it was a team movie. Thank you so much for having us all on, Steve. I really appreciate it.

NDADI: Yeah, thank you so much. This was awesome.

RIVERA: Yes. Thank you.

RAMIREZ: Thanks so much.