Behind the Scenes at SNL's Short Form Videos

Editors (and brothers) Sean and Ryan McIlraith dive into what it’s like to work on Saturday Night Live’s famous digital shorts, the insane time crunches, and more.

Today on Art of the Cut, we’re talking with brothers Sean and Ryan McIlraith. They are editors at Saturday Night Live and have edited many of the digital shorts that have gone viral over the last few years.

Sean’s been on the show as an editor since 2013, and has also cut episodes of That's My Time with David Letterman, The Tonight Show starring Jimmy Fallon, and segments of NBC’s New Year's Eve show. He’s currently cutting a feature film with some SNL alums. Ryan’s been at SNL since 2018 and has been an editor there since 2019. He’s also cut on That's My Time with David Letterman, It’s Bruno, and The Hardest Job in Sports. Both brothers also cut short films and TV spots.

Sean and Ryan McIlraith Discuss editing the Digital Shorts for Saturday Night Live

It's super great to have you guys both on the show. And thanks for joining us. You sent me a little list of some great shorts — all of which I think I'd seen except for maybe one or two of them on the show itself — is there anything else that you guys do for the show beyond those short pieces?

SEAN: I actually started at that show as a post-production intern, and I worked my way up from assistant editor to finally editing, but the first thing I edited for the show was their promos. They call them Tuesday promos. They do them with the host and they're almost like mini-pre-tapes themselves. I actually used to say they were harder to do than the actual pre-tapes because they would shoot with the host starting from 2:30pm or 3:00pm. They would wrap at 4:30 or 5:00 and you had to have a 15-second promo ready to go to the network in prime time that night. I used to do that. That was actually the best training to move into the pre-tapes. But I used to also co-produce a digital, behind-the-scenes series called Stories from the Show. Other than that, Ryan and I have just been sticking with doing the actual pre-tapes, which is where our passions lie.

RYAN: For me, at the show, I've only ever done the pre-tapes. I came in as Sean's assistant, actually.

Well, the pre-taped segments are great. And for me, one of my favorite sections of the show. Let’s talk about the short called Papyrus. That's one of my favorite shorts of all times. One of the things that I noticed is that it has a great use of cinematic language. You’re using the typical language of cinema to tell these stories in a very cinematic way. Is that something you guys study in an overt way when you look at films and you think, “Oh, I see why that looks so cool or why it tells the type of the story?”

SEAN: We actually co-edited that piece. That piece really jumpstarted a lot of stuff for us. We were still very early in our careers. Ryan, you might have been 23. I think I was 25 when we cut that. It was the first piece we edited that went viral. This was a big thing. The script was written by Julio Torres, who was a writer at SNL for, I think, three seasons. He was so great at making these offbeat little observations. When we got the script, it didn't fully gel with us. I remember Ryan and I wondered, “What is this going to look like? What is this going to be?” And it was directed by Dave McCary, who we started our careers at SNL editing for. What we really loved about Dave in terms of the cinematic language was that he was very uncompromising. He would try and make the pieces as truthful to whatever you were parodying as possible. So having Ryan Gosling and doing that piece, as this strange character study — if you watch the pacing of those cuts, it's not as rapid fire as some of the other pieces we do. It's a lot more labored and takes its time. And I think that's half the success of that piece. It finally reveals the Papyrus logo with the voiceover on that long dolly shot of him tapping his cereal bowl. It takes its time.

You almost have to understand all, if not most, genres of film, because you're constantly parodying them. Whether it's sound design or score, you have to understand the cinematic grammar of that, so that you can know, “This needs like a reverse cymbal scrape on this reveal.” Especially because you sometimes only have 24 hours to cut a piece. You need to have a basic fundamental understanding of the cinematic grammar of multiple genres so that you can just hop right into a piece. So I think Papyrus, more so than a lot of pieces we did, really lent itself to being able to jump into that genre of a dramatic character study — almost like a Darren Aronofsky film or something.

RYAN: I remembered that piece in particular shot until 6 a.m. on Saturday. The way that SNL works is that that piece needs to be done by 8 p.m. for dress rehearsal. I remember when I saw the footage for that, being a little nervous because it was so well-shot and it's so cinematic. And they spent a lot of money to have a car rig. So since it was shot really well and the script was really good, it's up to us to screw up. I remember thinking, “This is not your typical SNL piece.” It's slow and methodical and there's a very cinematic approach to it. Sean and I have always had the same taste in movies and TV for our whole life. I think I did the overnight on that one and then I handed you the keys at 6 a.m.

SEAN: Yeah, we switched off and you came back at around noon or 1:00pm. For us, it wasn't fully gelling about how they were going to pull it off, but I remember that you had assembled about half of it, and there was that part where Chris Redd says, Where else do you even see this font?” And Ryan smashes the bottle. You could see Ryan Gosling's commitment to that performance. That was like an “Oh shit!” moment. At SNL, sometimes you get a piece — and I relate it to fishing where your fishing pole bends over, and you think, “Oh shit! We got a big one!”.

RYAN: I also remember you walking in and I showed you that take of Ryan Gosling yelling, “I know what you did!” It's such a committed performance for such an insanely ridiculous premise that I knew, “Okay, this piece is really going to work.”

SEAN: It almost got cut. It played in the last 10 minutes of the show. That's the Cut Zone. During Weekend Update, you can turn on the sound from the control room — it’s called the PL — and you hear them making changes and sketches collapsing and the director and the script supervisor and producers all scrambling. I remember us being in the edit room thinking, “Oh my God! We might, not make air!” And it aired 10-to-1. It aired right in that Cut Zone. We were very proud that we made it.

It was such a committed performance. That performance could be in any Ryan Gosling movie.

SEAN: 100% yeah.

The Grouch is another classic take on the Joker trailer. How long do those take to shoot and edit and what do you guys do to speed up the process? For example, you were just saying you have to tag-team the editing. I’m assuming that you’re also probably editing while they were shooting. You can't wait until the whole thing’s shot, right?

RYAN: Sean edited The Grouch, but to speak a little bit to the process of how SNL works: The Grouch started shooting around 7 a.m. Friday. We usually have a team of assistant editors. My assistant editor, Paul Del Gesso, is great. Basically, they'll be ingesting the footage and making string outs — “action” to “cut” — per set-up with overhead markers. This way we can go really fast. We can find them super easily and pop them in. So they're doing that as they're shooting. And then typically Sean and I will come in about 3 hours after the shoot starts and start cutting scenes as they're being shot. So the footage is basically being shuttled back and forth between 30 Rock. So we're essentially keeping up with camera, which becomes very taxing all the way up until Saturday night.

SEAN: This was pre-COVID. It was the fall before COVID. So that was back when the film unit could go physically to places. They actually went to the iconic stairway where the Joker danced down the steps and shot that with the Grouch. They were all over the city. I probably started at 1pm or 2pm.

That is sort of the classic SNL film trailer parody. That was directed by Paul Briganti who Ryan and I worked with at SNL for years. Amazing director. Amazing person. At first, you have to cut together these little vignettes, then you have to piece them all together. For example, there’s a part where Bert and Ernie get mugged. For that, Paul shot a full scene from start to finish. You see the guys walking and then the robber shoulders them and then they have this whole confrontation.

That was one of the first things they shot. It was one of the first things I was cutting together and I was sending Dropbox links to Paul. After a couple of rounds he said, “Just take the main essentials. I don't need the beginning and the end.” But it's hard because you're working parallel with production. It's hard to imagine that until you have all the pieces of the puzzle there, right?

At the end of the day they got a stand-in for David Harbour and just started shooting a bunch of B-roll. The Grouch going down the steps? That's not actually David Harbour. That’s a stand-in. But until you have all that B-roll and all the extra stuff, it's hard to get see how a scene is going to fit in the puzzle.

Usually, at SNL you stay until six or seven in the morning on Saturday, until you have a full cut. It might not be sound designed but you have something that's standing on its feet. But I remember that piece specifically, and they went until late in the morning and it's hard to take these vignettes and make it a cohesive whole that feels like it's really ebbing and flowing into each other.

So I tapped out at two in the morning and I'll just come back at six, you know, I'll get 3 hours of sleep and come back once I can take a bird's eye view of all this stuff. And that was actually very helpful for me because film trailer parodies are big in scope because when they do an actual movie trailer, they have a two-hour movie that they're condensing into 2 minutes and change, but we're faking that. We don't actually have that. We're trying to take all these little vignettes and little pieces of run-and-gun B-roll and trying to make it seem like this is based off a two and a half hour movie or something.

I'm so proud of that. The audience just started applauding halfway through. When that happens it's like having a fish on the end of your pole. It was just like “We did it!” Sometimes it doesn't work out that way. That's the other side of SNL: when a piece bombs and you got 2 hours sleep and your team killed yourselves.

RYAN: But SNL is also such a fun, interesting place because I can't think of anywhere else where you work that hard for so many hours and then you literally hit export and 10 minutes later, it's on air and you're sitting with your team and you just worked for 30 hours nonstop and then you get to see whether or not the audience loves it or hates it. And it's in such real time. I remember that one watching on air and thinking, “Man, the audience absolutely loved this piece.”.

SEAN: It's such a special place and it's so inpidual in terms of the industry because even if the piece bombed, or you get cut from air, you get to swing again next week. TV or long form movies, you work for months and you know, it bombs at the box office or gets bad reviews that was six, nine months. But at SNL it’s like a full-on marathon for two days. But, if it doesn't work out, it's like, “Okay, this time next week, like let's try again.”.

The other thing I noticed with the Grouch — and you were talking about how much the audience loved it — it's an interesting creative choice that you hear the audience reacting to the short because you wouldn't have to do that, right? You could just literally play the short turn off the microphones in the studio and let it play. But they don't. You get to hear the audience laughing along, which I think is great. It's very cool.

SEAN: It's either is the most soul-crushing thing on earth or the greatest feeling. You're always chasing that high where an audience really goes crazy for a piece because there's no other environment in this industry where you really get that immediate gratification.

Is there anything else you guys do to prepare ahead of time? Like I noticed in the Grouch piece that there were shots pulled from the Joker movie, correct? Are you looking at a script and thinking “Oh, I need this sound effect before we even tape or this stock footage.”

RYAN: 100%. Usually we get scripts on Wednesday night. On Thursday I have a pre-pro call with the director. In the meantime, I'm going through the script and marking things with a highlighter: here, I know we're going to need x sound effect. Here I know we're going to need these sound effects and then I'll mark with a different color where we need music and I'll have a call with my assistant talking through, “This is what we're going to need,” and then I'll do a lot of preliminary pulls based on what I think the piece should sound like. A lot of it's just pulling a lot of music and sound effects. For stuff like stock footage, that stuff doesn’t actually come to us until we start editing. We know in our minds we're going to have to use shots from these trailers, but we don't actually get that stuff cleared until we're in the thick of it on Friday. So a lot of that stuff comes later.

For the most part we're doing a ton of sound work prior to starting because for these digital shorts, it's so important for them to sound like they've been fully sound-designed and they haven't. We're just doing all the sound design. So when I first started doing the shorts, I would actually take a Premiere project and do sound before I even saw any footage at all. I would do sound design the day before I started editing, just to make sure I had all my sound beds in and then I could just solely focus on the picture. And I can know that if I dropped footage then it would at least sound like it was in the environment. With how fast we are cutting, we kind of have to do it beforehand.

SEAN: That's one of the biggest lessons that I've taken from SNL is how important sound is to a piece. And at SNL, we are the sound designers. There's no back up. If you do a horror movie trailer parody, the scoring on that stuff is such a nightmare. If you see the new Scream or Halloween, there's so much sound design and scoring. You need your piece to feel legitimate.

When I came in on Friday, I would spend an hour or 2 hours, and just pull sound effects and mark up the script, pull score, pull a bunch of different music tracks. That way you’re set, for example, “I know I'm going to use this score for this beat.” I have all this work already done for me so that later in the process, when you're in the thick of it and doing writers notes, producers notes, cast member notes, you have those sound beds built or that work already out of the way, so it makes your life as you're heading towards the 11:30pm cutoff that much more easy and you feel settled in going into the day.

I was just thinking about the fact that most of the editing that I do, I'm using temp score, which I know is going to get replaced. But you guys, that's got to be music that is licensable or scored. So where are you getting music from?

RYAN: SNL has the NBC stock library. So it'll take usually a little over an hour to really look through everything and make sure we're pulling the right stuff.

I actually just did a sketch this past weekend. It was a bank robbery piece with BeReal. And we wanted to use this famous song called Be Real. Very famous song. And they were like, We need to put this in the sketch. We have to license it. But the producers weren’t going to be able to reach out to the estate that owns the song. So we were able to find a workaround and get a karaoke version of it that sounds similar and get that license. There's a lot of music supervisors at the show that can help us do stuff like that. But for the most part, Sean and I are really just digging into pages and pages of sound libraries trying to find the perfect score.

SEAN: Yeah, I love APM. APM’s stuff is really, really great. I really rarely had a problem using APM. I did a sketch last season called The Good Variant. One of the producers was friends with Chris Martin from Coldplay and asked, “Can we use your song?” And Chris Martin was apparently like, “Yeah, great.” So sometimes you get to use these actual big songs in your piece. That always helps because sometimes you go to air using an actual, very popular song, and then after it airs — for the web — or syndication you replace it with a stock thing. That's always a bummer. So after it’s gone to air you have to find a sound-alike.

RYAN: Because if you have to find a soundalike, the writers get so tied to the actual song that got into the piece, and then you're looking for the soundalike and it never will sound quite right. So they're never going to be that happy with the piece that goes to the web with that song.

With Walking in Staten you have to know going into even writing that piece that you're going to get that song license, I would think.

SEAN: I think that's the Pete Davidson charm. He was just able to get Marc Cohn to be in this piece and let him use this song.

You were talking about the difference in pacing between the pieces. For example, Papyrus, as you said, is very restrained, very few edits, not a lot of fast edits. And then you've got Walking in Staten and there is just a ton in there editorially: lots of coverage, lots of footage. I can't imagine doing that on a schedule! How do you cope? What do you do to be able to do something creatively and yet efficiently?

RYAN: I think when you're faced with that much footage, it's very easy to get overwhelmed. It's very easy to look at this footage and realize there's no real end in sight. The best thing to do is just to start cutting — is to just make a decision. Because once you start, it's easy to start building on top of that. The most crippling part of being faced with that much footage on a timeline where you need to be on live air with full color, full mix in 24 hours is just start. Once you start, you can build on top of that. Sean, what do you think?

SEAN: I totally agree. The hardest part of any editing job, SNL especially, is just that anxiety of 5:00pm on a Friday or even 4:00 on a Saturday morning, which — probably half of the pieces we ever cut at that show we start at four in the morning on Saturday. You're just scared to death. Your heart is racing. It's 4 a.m. I have so much footage. It's a music video. The writers are going to come in at 2pm. The director is going to be here at noon. I got to get it cut.

It's like this thing that you never trust yourself. I think that's something I very much struggle with as an editor. Ryan and I talk about it all the time, but you have to be able to trust yourself after a certain point that we've done this before. I trust my instincts. We're going to get it into a good place.

Once it's standing on its feet, even if it's a rough assemble — audio pops everywhere — it's not sound designed. It's empty. You know there are issues that you need to work out. Once it’s on its feet, then you can take a step back and see, “Oh, okay, this isn't working. We can take this piece out. I need to do this.”

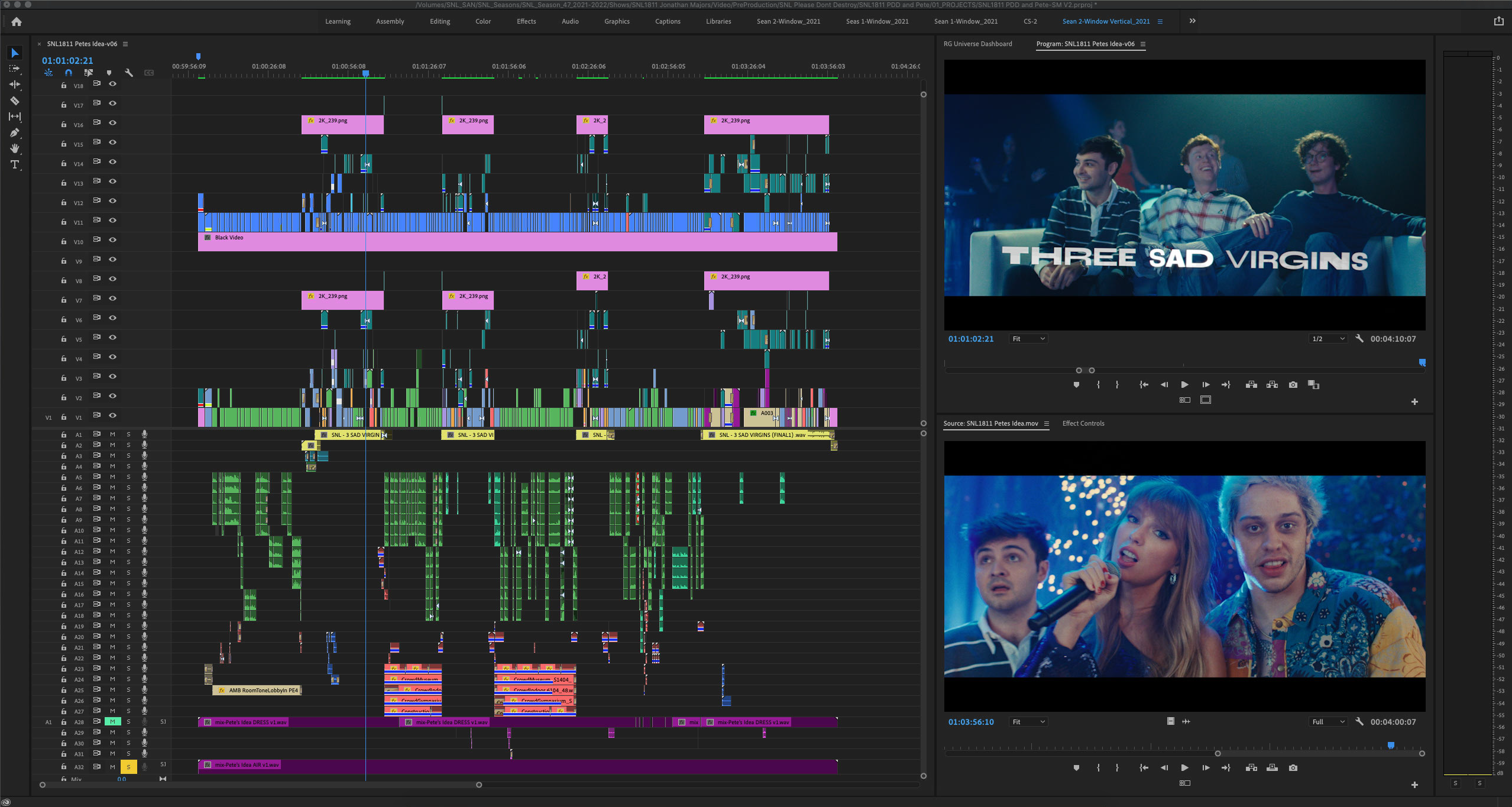

Specifically, something like Walking in Staten — that's a little bit of a different case because they actually shot that on a Monday, which was interesting because that week I ended up cutting two pre-tapes. That Walking in Staten one, like any music video, it needs what I call “the sauce.” You cut the music video. You find the best performance and you almost cut it like it's a live performance.

Our assistant editors do stacked sequences in Premiere. We learned this from one of our old editors that we used to assist for — Jeremiah Shuff — he used to be Beyonce's music video editor. He's like one of the best music video editors ever. He taught us this trick of these stacked sequences where you take all of your footage and you just stack it up, right? I've had stacked sequences that are 200 video layers high, but it's the best way in an efficient manner to find the best take of like a line of dialogue or certain performance because you just set your in and you just start unbinding video layers.

The assistant editors color code. Here’s Pete single or in front of a green screen. That's color coded with adjustment layers on the top and the bottom. Then underneath that is a different color. Once you build out the music video in terms of performance, then you can consider, “Okay this is a perfect part for this B-roll.” And then you get into the nitty gritty of “the sauce” we call it. That includes stuff like the pumps and the flash frames and stuff, the bounces, the lens flares and stuff. All that little stuff that just makes it pop even more. That always comes last.

Sometimes writers come into the room and they're like, this is a trap video. It needs to be more exciting. But it's two in the afternoon and you have to tell them, “I know that. That's coming. We’ve got to get this cut up on its feet first in terms of takes and performance.”

Ryan did an awesome music video, “Stu.” And that shot until four in the morning, right? Once you, do a couple music videos, you have these certain things in your arsenal like those bounces or those flash frames.

The bounces you're talking about are like a pulse of scale?

SEAN: Yeah, yeah. And in Premiere we put them on an adjustment layer above and just keyframe it.

RYAN: Stu shot until four in the morning. And that was a case of getting started Saturday morning because it was such a big shoot in scope and they were shooting so much coverage and it took place half in Santa’s workshop and half was music video in a basement and then also Pete driving in a rainy car at night. So there was just a lot to edit in that.

A lot of what Sean was talking about — like adding the bounces and stuff — that's something that we pull from an arsenal. If we're doing a music video, we know we're going to add some bounces here. But Stu is an example of something that was parodying a very specific music video. It was the music video “Stan” and that didn't have any of that stuff. They really wanted to keep it grounded and keep it very similar to what the music video was. So a lot of that was just straight cuts.

I remember I actually don't think I had a cut in until maybe 3 p.m. or 3:30 p.m.. So I was finishing up the cut while the writers came in, which is really stressful. As Sean was saying, the most important thing there is to get a cut done, because then you can take a bird's eye view. Then you can start swapping takes. But you just have to finish a cut first. Once, 11:30 p.m. rolls around, you have to go to air. So if you have a cut done, at least you can go to air with that.

With that one, I remember, we worked up until the very last moment because there are these scenes in Santa’s workshop and originally those were full scenes — scripted scenes with dialog. I remember the writers saying, “Every time we cut out to these scenes, it's sort of pulling the energy away from what this piece should be.” So we worked with Eli Brueggemann, that made the music, and asked, “What if we made those part of the music video also?” So we ended up just making those into little music interstitials. So we completely recut those and they're no longer full scenes. They're just music interstitials that keep with the beat, keep with the song. But that was something that didn't happen until like 5:30 p.m. or 6 p.m., and then we were scrambling to get that done.

I remember when that one played on air, people loved it. As soon as the camera cranes down into the basement, they were like, Oh.

Now I get It.

RYAN: Now I get it. This is the Stan music video. People started cheering, and we were so relieved. My assistant editor, who is incredible, Paul Del Gesso — stayed up for 30 hours straight with that one because he was scrambling to make sure all the footage was ingested.

SEAN: They were so stressed, and it was crazy. And I remember I was afraid to be in their edit room, so I just kind of stayed away. And I remember hearing the audience roaring over all the TVs on the 17th floor in 30 Rock. The sketch had only started 20 seconds before, and I thought, “Oh man, they knocked it out of the park."

%20watches%20STU_December%205%202020.jpg)

I wanted to jump back to something you were talking about — APM — because I was just in a Twitter discussion with people about “What's the best music library?” We used APM when I was at Oprah for a decade. That's a solid music library, for sure. What kind of watching of the “Stan” video do you do to see the kinds of things that you need to pull off to make that feel real to the audience?

RYAN: 100%. Initially, for that one, I remember I just watched it on my own, and I took notes in my Notes app: there are no fades or dissolves or anything. So I thought, “we just have to keep these straight cuts.” It also didn’t have any of that poppy stuff. So we just need to keep this one grounded. I had somebody at the show pull me the actual Stan music video, so I put it in the source window and kept looking at it as I was editing to make sure I was keeping it within the world of that music video.

Again, the writers, Dan Bulla and Steven Castillo, were so adamant that they wanted that one to feel like a direct parody of Stan. I think I watched that at least five times before starting. We have to work so fast that there are things that I wish I included in there, but at the end of the day, I'm super happy with that one and how it came out. You always look at your pieces afterward and wish I did something different.

With the Stan music video, there's a great shot of a car plunging off the bridge and that would have been a great “out” for that video. It's one of those ideas that as soon as you hit export and as soon as it goes to air, you're thinking about it. It still haunts me till this day that we didn't end it like that.

The watching of any of these things, like the Joker parody, the Grouch parody, MacGruber with watching a MacGyver episodes. I'm interested in your process of watching and thinking about these kind of cultural touchstones and what makes them what they are. I love your idea of you're going through the notes saying there's not a lot of funky stuff going on. This one is pure cuts. What are some of the other things that you're seeing when you're watching cultural touchstones that you're trying to mock or satirize?

RYAN: MacGruber was one that I edited. Sean edited one of those, too. There were three in the episode. I remember when they were going to revive that character, I went and rewatched all of the original ones because I really wanted to understand the pace at which those were edited, because I think a lot of the times SNL shorts can be cut way too fast and they can be cut within an inch of their life — where it's hard to actually follow the jokes. And with MacGruber, while they're edited really fast, each joke is given enough time to land. So I remember watching that one thinking, “We can hold on this. We don't have to cut it within an inch of his life. We can hold on this a few extra frames or an extra second or two to make sure the audience gets it.”.

Especially with the MacGruber coronavirus one. When you finally understand what the punch line is going to be.

RYAN: Then it's interesting because once the audience is on board — once you've revealed what the game is — you can start pacing it up a little more because once you've done the initial reveal then you can start speeding up the pace. Then you can start really doing joke, joke, joke, joke in rapid-fire succession. But leading up to that, you really want to make sure that there's a build long enough for the audience to grab onto.

SEAN: Last year, we did a Squid Game music video with Pete, and I was cramming, watching Squid Game because I hadn't watched any. I thought I really needed to absorb all this. Then when I started cutting it, I realized that nothing I watched really related to how I’m going to cut Pete and Rami Malek in that video.

For the Grouch, watching the Joker trailer and getting into the world of dissolves to black and dipping out and the sound design — like those low whooshes into a bassy hit as it cuts to black. That was one where I could ground myself with, “how do I relate to the source material?” But sometimes you’re taking something like Squid Game, where other than production design and the visual effects, and costuming — that’s all Squid Game. But in terms of the cutting, you’re really making it into your own thing.

There have been shorts we both cut that are based off of things that we've never watched before, because at a certain point, it's a job and you're just rolling into every week and it's hard to watch a full season of television after you get a script that Wednesday night.

One of the other videos that you guys pointed out to me was The Duel. And the pacing of your short has to be much different than the source material you're trying to basically have a two minute video that is representing a movie. Talk to me a little bit about telling a narrative story in that short amount of time, especially in reference to The Duel.

RYAN: That's a great question. I remember us getting the script for that and thinking, this is going to be super cinematic. That was one of our earlier pieces. Our first cut of that we tried to keep it a little more grounded and you keep it loose. It starts out by playing a little fat and then once you actually need to hit an air time — like, this has to be 3 minutes — then you have to start really pacing it up. I think The Duel was one of the longer ones, and then we sort of paced it up a lot on Saturday.

SEAN: We did co-edit that one together. That was based on The Favourite.

In terms of the editing style of The Favourite, our piece probably had nothing to do with that film, but the cinematography and the framing is very based off of that film. But the pacing of it — you don't want to tip it too quickly. But once the rollercoaster finally comes over the hill and goes down and the bullets start flying everywhere. That's when the pace starts to pick up. We would love if we had 6 minutes to let a piece really breathe and play out, but it's not the reality of that show. Sometimes a producer comes in says, “This needs to be like 3 minutes long or you're not going to make the show.” That's just the reality of a 90 minute live show where they go into it with four too many sketches. One of your best ways to avoid getting cut is to keep it below 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

With The Duel, as far as the pacing goes, the first 30 seconds, 45 seconds, is settling into the vibe and the milieu of it. Then once Sandra Oh gets shot for the first time, then the bullets start flying and the editing and the camerawork gets a little faster and you’re just trying to get those jokes to hit one after the other like train cars banging into each other.

Speaking of the amount of time you try to get them down to, what are the running times of some of those before you realize that they're too long? Like was The Duel 7 minutes and you realized that you needed to get to three? They're never 7 minutes. A lot of pieces are about 5 minutes. Then they tell us, “You've got to get it down to 3 minutes.” We've become very good at killing our darlings very fast.

RYAN: I also think SNL has sort of corrupted our editing sensibilities.

SEAN: That’s actually probably a good point.

RYAN: Because you look at stuff like The Duel and I as someone that loves film and loves The Favourite would love to hold on these shots, but also I, as someone that edits SNL digital shorts, knows that we have to cut away from these shots and know that we have to get this thing down to 3 minutes or 3 minutes, 30 seconds.

SEAN: One of the benefits of SNL is that it really teaches you to not be precious. Before Ryan and I were at SNL and working with the film unit, we were budding filmmakers and we worked on our own stuff. We were doing 12 minute short films and just taking months and overthinking everything. But since SNL, now when we go into other projects, we think, “Oh yeah, that's funny, but it's not benefiting what we're doing. And it's a little bit softer of a joke, so even though it looks beautiful and I'm proud of it, and it was a pain to get those shots, kill it. It’s not working. Take it out.”.

RYAN: It’s so true. I actually just did a piece this past weekend where I was having a ton of trouble. There was an ending montage — it was for the Please Don't Destroy guys. We got an ending montage — all slow motion, set to classical music, and it took me 3 hours to edit and really had to dig deep and figure out how to cut this thing, even though it's only a 15 second montage. I sent it out to the writers and the first note I got back was, “Let's just cut that. It's not really working.”

Damn, I just spent so long trying to get this thing to work! I stayed till 4:00 in the morning to make this thing work. But as soon as I cut it, I thought, “This makes perfect sense. Now the piece is going to have a proper ending.” I realized we were just extending the piece to extend the piece.

That brings up an interesting point, which is handling creative notes, which it sounds like you guys obviously have to do with the writers. Let’s talk about not taking that stuff too personally. Or let’s talk about how things are moving so fast so when you get a note, that note's got to be done instantly.

SEAN: Most, if not all the other editors you've interviewed on this podcast have said, you can't take it personally, right? It's not an indictment of you or your editing skills if somebody says, “This isn't working” or “This can be smoothed out.” As we were talking about before, the hardest part is getting a piece on its feet. Even if you know there's problems, the most important thing is just getting the first cut, because once you have that first cut, you can step away.

But I remember when we first started editing at the show and we'd be playing it down for the director or the writers for the first time, you're wincing every time there's a nasty cut or you haven't figured out a smooth transition or the sound is just terrible. That's part of just maturing as an editor. In terms of taking notes, you have to be able to take that criticism.

RYAN: It's also recognizing that when you're given a note, everyone's giving a note for one common goal. They're giving notes to make the piece as funny as it can possibly can be. They're not giving notes from an ego standpoint.

But at SNL, when we're given a note, it's to find what's the best version of this piece and what's going to get the best laugh. So Sean and I have come to understand that. We don't take notes to heart. A lot of times we'll send a cut out that we think is in great shape and we'll get 25 notes back. We'll maybe piss and moan for 5 minutes but we don't have 10 minutes to do that. We have to start moving.

Then once you start working through those notes, you see, “Okay, well now I can see the forest for the trees.” And you start seeing that the piece is getting better. Like a joke that I thought was funny — yeah, it was funny, but there's three jokes after that are just as funny. So you're really just working towards one common goal and just making sure that the piece is as funny as it possibly can be.

SEAN: There's a writer, Dan Bulla at SNL that is so good and so funny. On Walking in Staten he gave his first round of notes and he said, “This isn't working at all. We need to change this.” I almost appreciate that more when you're just straight forward. Even if you don't agree with an opinion, you know it's coming from a good place. It's always to help the piece, and it's always to better the show.

Sean, you’re cutting a feature now with some of the SNL folks. I did a lot of short form before I did long form. Are you finding that it is a challenge to slow yourself down in a feature film after cutting so much shorter form stuff where you're trying to compress massively?

SEAN: Definitely. It's been interesting working on a feature compared to working in short form because you're thinking a lot more about story and a lot less about whether or not these cuts are exactly working in this little scene or is this setting up the next 30 seconds? You're really thinking about story. Is this character developed enough? Is this scene working towards setting up the stakes of what comes next? Thinking about scenes in the sense of, “Is this fully showing what this character wants?”

It's definitely been a change. It's also interesting for so many years working in Premiere and then going to Avid. I originally learned how to edit in Avid but especially in New York — working in New York for so many years everything is cut in Premiere. So that's been an interesting part of it too.

But definitely in terms of the storytelling aspect of it, it's almost like a breath of fresh air. You work on these scenes and at the end of the week, screening the film, and taking a step back and thinking about character motivations; thinking about how the stakes are being progressed; I honestly am enjoying it so far. It's cool.

Have you always cut at SNL in Premiere?

Have you always cut at SNL in Premiere?

SEAN: Yeah.

RYAN: Yeah. Always. Always. I think it’d be really hard to cut in Avid there because we are just doing so many graphics and working with so much mixed media. It'd be really hard to be able to pull stuff in. I've only edited briefly in Avid, but I know it sort of struggles with that.

I know it's great for long-term storytelling.

SEAN: We did the Eric Andre show over the summer, which was an awesome, great experience and by the end, doing those full episode assemblies Premiere was getting a little bit slow and it's just not as stable as Avid, but working in Premiere for SNL I don't think Avid could handle it. Premiere is so nice to ingest stuff and immediately start working.

I’m cutting a TV series in Avid, but I’ve got a personal documentary I'm working on and for very specific reasons, I'm doing that in Premiere. So you won’t get an argument from me about NLEs. I jump between them depending on what I think their strength is.

SEAN: Whatever works for the project. Whatever works for you. Stop arguing about dumb stuff.

I'm 100% in your camp on that. Have either one of you guys thought about directing these?

RYAN: Yeah. Sean and I think about directing all the time. We've directed a bunch of films and it's funny because every director we work with started as an editor. It's great when you work with a director that's been an editor because they think like an editor.

SEAN: Directing is definitely where our passions lie. The best directors I've worked with so far in my career have been editors, especially working in short form and especially working in television. You need to have that brain power of efficiency in terms of knowing what you need and this is how I imagine it being cut together. I find a lot of the times that editors are just sharper with that.

The only other thing I would like to talk about is the post department at SNL. It is the best post team in the business. The people at SNL — the assistant editors are just the hardest working people you will find. The visual effects artists do the impossible every single week. There are so many people behind the scenes syncing that footage, ingesting it, making those string outs, making those markers to make the footage that more digestible and easy to navigate.

The post department team at SNL. It's come a long way. When I first started, it was very bare bones. There’re people like Kelly Lyon and Adam Epstein — who I know you've talked to before — who really paved the way for it. Back then there weren't that many assistant editors. When I used to assist for SNL, it was really just me. Now it's so much bigger of a thing. And it needs to be because the pieces keep growing, especially with COVID, they shoot a lot of these pre-taped in studios now, which means, that there's much more green screen and set extensions because the pandemic unfortunately made it harder to go and shoot on the real location.

I think we can’t understate it. The entire post department team at SNL, they are just the best of the best of the best and the hardest working people you'll come across.

RYAN: Every single one of them has saved my life multiple times on multiple occasions. The assistant editors they're not credited as assistant editors anymore. They get credited as editors because so much of what they do and so many of the assistants that Sean and I work with are also assembling scenes. And they're doing a great job. A lot of them are great editors in their own right.

You asked the question about what we do when we have a huge volume of footage. A lot of times Sean and I will say, “It's a 12 page script. Could you assemble pages 7 to 9” and they work really hard on top of doing all the ingesting, on top of doing all the string outs, they work super hard on making these scenes feel good and sound designed. And we can't understate enough how much we love working with them and we appreciate everyone there.

SEAN: Our old assistant editor, Chris Salerno, he's now editing pre-taped shorts after years of being the person in the background who put his head down and did the work and worked so hard, and now he's graduated to editing shorts himself.

What's the staff like size-wise? What are you using gear-wise to allow you to have all these people working at the same time and making your deadlines?

RYAN: In terms of staff size, for the visual effects department, I think we have about 15 visual effects people now.

SEAN: It might even be more, honestly. It grew exponentially after COVID.

RYAN: If you look at any one of our shorts, we've done edits that have 40 VFX shots, and those are all done in one day and they're done incredibly. Yeah, there's probably 15 people on that. For assistant editors, we have about three assists per piece because they're just shooting so much. We have a great post supervisor, Matt Yonks. We have sound mixers inside the building. Color is done out of house. We send a looks EDL in the morning of all the shots. They're coloring all throughout the day as we're going and then we send a cut. Our great assists will try to keep up with us and overcut the color while we're still making changes.

SEAN: The typical SNL day is they'll typically shoot Friday morning, afternoon until Friday evening. A lot of the times they will shoot Friday night into Saturday morning. And what happens is there are media managers on set because they shoot in studios in Manhattan — and they take that footage and they are connected to the SAN back at 30 Rock and they send the footage and ingest it to the SAN.

Then there is a team of assistant editors — it's typically three assists per pre-tape — who are then taking that footage, bringing it into Premiere, syncing it, logging it, making markers, stringing it out, doing all that stuff.

Ryan will typically come in at two in the afternoon and start cutting. You cut until maybe six in the morning on Saturday to get that piece on its feet. While that's happening, an assistant editor has sent a looks EDL, which is just basically a shot from every set up. The colorists are Josh Bohoskey of Visual Creatures and Elias Nousiopoulos and they start first thing in the morning on Saturday setting looks with the DP's and they send screenshots to the directors so that the directors can approve looks while they're in the edit room at 30 Rock.

Directors usually come in at noon and start working on the pieces. And writers typically start popping in around two, 3 p.m. and that's where you really take off. Producers will come in maybe around like four or 5 p.m. and they'll give their notes, do whatever, and you're working up until maybe like seven, 7:30pm.

Then at that point you send to mix. The mix is usually happening in 30 Rock on a lower floor and they're mixing and your assistant is connecting the color, if you're trying to get color for dress. Dress starts at 8pm. If you’re earlier in the show, you'll go to dress at 8:30pm and usually more often than not you have a ton of notes. The piece that went to dress might have been 4 minutes and you’re trying to get it to a 3:15 runtime, so you're just slicing and dicing until like 10:30 at night.

While that's going on, you need to be “cutting across the mix.” This way — when you send to mix for air — the mixer can see where you've physically made changes. They can take the 5.1 mix and they see it at the bottom of the AAF or OMF and they see where you pulled pieces out or you added new stuff.

Then your assistant editor, is sending any new color pickups, if you added new shots between dress and air, they're sending pickups to the color house. There's also visual effects. I think my record at SNL was 82 visual effects in a pre-tape.

That had to be done in a day!

SEAN: Had to be done in a day. And while that's happening, you're almost cutting your losses because if you shot 4K, you want your VFX to come back in 4K. But to make the process easier, usually more often than not, we get the effects back at 1080 because it just takes too long to render out.

The race between dress and air, there's just nothing like it on planet Earth. I can't tell you how many times I hit export while the control room is calling the editing room because you're going to air in 5 minutes. There are so many times we export and we haven’t even watched the piece down. You're watching it live on the TV, rocking back and forth, feeling nauseous.

Things have gone wrong on air before. I've seen it happen. Luckily not that many. It's such a crazy process. Ryan, do you remember a piece we did where I was sprinting down to the mix because we weren't going to get a mix in for air. I was saying, “Just use the mix in the export! Just throw a compressor on it!” That’s the craziness, the heartbreak, but also the fun of that place. Where else does that happen on planet Earth in this industry where you're running down 30 Rock at Christmas time begging the control room to use your mix from your export?

RYAN: I just remembered a quick story about something similar. I did a piece called Tiny Horse, which was just basically Timothée Chalamet talking to a literal tiny horse, so there were 65 visual effects shots. The horse wasn't there. It was just him talking to plates the whole time. That was during COVID and we weren't allowed to have more than one person in the room. I was working with two directors at the time. One director was in the room, the other one was sitting outside, but there was a glass window and my assistant editor was working all the way down the hall. We didn’t have any of the VFX and we had like 16 minutes. My assistant editor, Paul Del Gesso, was at a standing desk crouched over, just conforming all these VFX shots so quickly. There were producers standing outside the room saying, “I don't know, this looks bad.” I said, “It feels terrible.”

Then when you see it air with those shots in, there's no relief like it. I never worked anywhere else where I felt that insane amount of stress, coupled with this insane amount of relief almost immediately. At 15 minutes where I feel like, “This is never going to work” to 15 minutes later, where you’re saying, “Wow! I don't know how that worked.”

But it's just because the people that work at SNL and the team that we work with is so dialed in and so diligent, and without them, we would not be able to get any of these pieces on air. If you ever want to grab a drink sometime, we'll tell you some horror stories.

Ryan and Sean, thank you so much for spending some time with us. It's really interesting to hear about this process and thanks for shedding some light on it.

RYAN: Steve. Thank you so much. Been such a fan of the podcast for so long.

SEAN: Yeah, thanks for having us.