Today on Art of the Cut, we’re speaking with Elisabet Ronnaldsdótir, ACE, about editing Bullet Train with her long-time directorial collaborator, David Leitch.

Elísabet started her editing career in her native Iceland more than 20 years ago. She’s spoken with me on Art of the Cut about Mile 22 and Atomic Blonde and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the 10 Rings. She also edited The Deep, John Wick, Deadpool 2, and Kate, among others. With credentials like that, it’s so easy to categorize her as the queen of the action film, but I think our discussion today will show that she’s so much more than that.

Art of The Cut with Elsabet Ronaldsdttir Editor of Bullet Train

You and David Leitch have worked together multiple times. You're a very talented editor and you give him great editing, but what else gets you asked back? What makes a director want to work with you again?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It's probably my hair. I don't know. It's difficult to say.

I do think you have to have likability, but you still have to push. That's what filmmaking is all about. If I walk into a room and no one is going to push me, it's like having nothing to hold on to. Filmmaking is a collaborative art so as a director, you have to be willing to be pushed as well.

David is so willing to experiment and have fun with the material. I do consider him and his wife Kelly family and I love working with them because they're so passionate about their projects.

That's great. I agree with pushing the director at some point and also allowing him to push you.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: You don't have to go where you're pushed, but you might have to consider it. It's a big part of our jobs to push, but in your work, you have to be extremely critical. You are constantly asking questions, like, why is this happening now? Why doesn't this happen after? When you watch the movie, you have to know what you love and what really works but you also have to watch it with critical eyes. I sometimes watch them backward without the sound and at different speeds. I always run all my reels at double speed, just to see.

Joe Walker said that he watches things black and white and flipped.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Exactly. It's the same thing. It can also be very helpful to watch it in different settings. What's it in the cinema? What's it on your computer? What's it on the TV at home? It always helps every new scenario you watch it in and will give you a new perspective.

You were talking about this idea of looking at the film critically and pushing your director. There is a montage that I loved, but I wanted to know whether there was a discussion of cutting out the Fiji water bottle montage.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Oh no, you can't cut it out.

What's the discussion that you have with David about keeping it or cutting it out?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: For David and me, it's just such an important part of the movie and it's what the movie is about. I think the studio asked about if we could cut it out, but neither I nor David nor Kelly were ever serious about taking it out.

In the beginning, a pair of assassins are debating whether they killed 16 people or 17 people, and it's got a real tone to it. Can you talk about constructing that montage and supporting the tone of what it's there for?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: That was great fun. David is very particular about tone. We just wanted to have it snappy and fast. It's just flashbacks to them bickering about how many bad guys went down.

I would guess that montage could have been much longer, but as you said, it has to be snappy. You can't divert the story arc for too long.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: This lovely idea that David had with Dominic Lewis, the music composer, was about using blowing bubbles like it's their theme throughout the movie. So that also helped set the tone.

Can you talk a little bit about keeping the length of that section down? I'm sure you could have made it 20 minutes long if you'd wanted to.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Oh yeah, in the beginning, it was much, much longer. We're in an action movie and we want to bring in some action early on. This was a good way to do it, but this has nothing to do with the movie. It has to do with building characters but it's not a part of the story of the movie. It's Lemon and Tangerine's backstory. David talked a lot about keeping Lemon and Tangerine snappy with as little air as possible between their sentences.

I felt that “no air in between their sentences” thing. How much of that was editorial, and how much of it was following their delivery?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It's a mixture of both. We wanted to stay as wide as possible. We usually have medium wides and we don't go much into the closeups, but it was all about building that character of the twins and making them as brief as possible.

There's a flashback to a character called The White Death and his origin story. You're cutting back and forth from one of the twins narrating the story. So what is the value of cutting back and forth between what's happening on the train and The White Death flashback?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: That was just to keep the storytelling going so we wouldn't disappear into another world. But this is a flashback that is repeated later in the movie from a different perspective. There was a lot of material and where to go and what to do, but it's all very well thought out by David and Jonathan Sela and the crew that shot this. It was all set up beautifully.

The question is always, how much information are you going to give up at this moment? But going back into the trainer stuff was absolutely to keep the characters in the story. I think it's a good balance, and the same goes for the Wolf, how he gets his whole life in a flashback. There were scenes we actually took out before just so we wouldn't foreshadow the Wolf before he arrived on the train. There was a huge structural change in the beginning because as the book is written and as the script was written, and as it was shot, it was chapters. You were introduced to each character by chapter. So they never really met until after every single character had been introduced for several reasons. One is time, it took a bit longer and when I started experimenting with having them bump into each other, we agreed that the notion of fate was so much stronger.

So the script was also chaptered. Wow.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It really works and then you have to translate it to the movie and it's a different language. In any language, you have to rearrange sentences and words just to get the same meaning across. So it's a translation that we felt worked better.

It's a translation, not just from the book to the script, but from the script to the finished piece. Did you read the book before you started editing?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I read everything. I need to know all of those things to be better equipped to understand what David wants. I read the book, I read different iterations of the script.

I've interviewed many people who've edited movies based on books and it's 50/50 whether people think they want to read the book or stay away from it.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I do think it's a personal choice. Whatever works for you.

There are a bunch of different stories. The train is filled with these assassins and they're all independent of each other. Did you always intercut their stories like they were in the script? And if not, what guided your choices of when to intercut?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It's kind of 50/50 if they left it where they were scripted. We experimented with moving some of them around, trying to find the best point to meet those characters.

What is guiding your decision to cut from one story to another story if it's not the script?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: You have to trust your instincts.

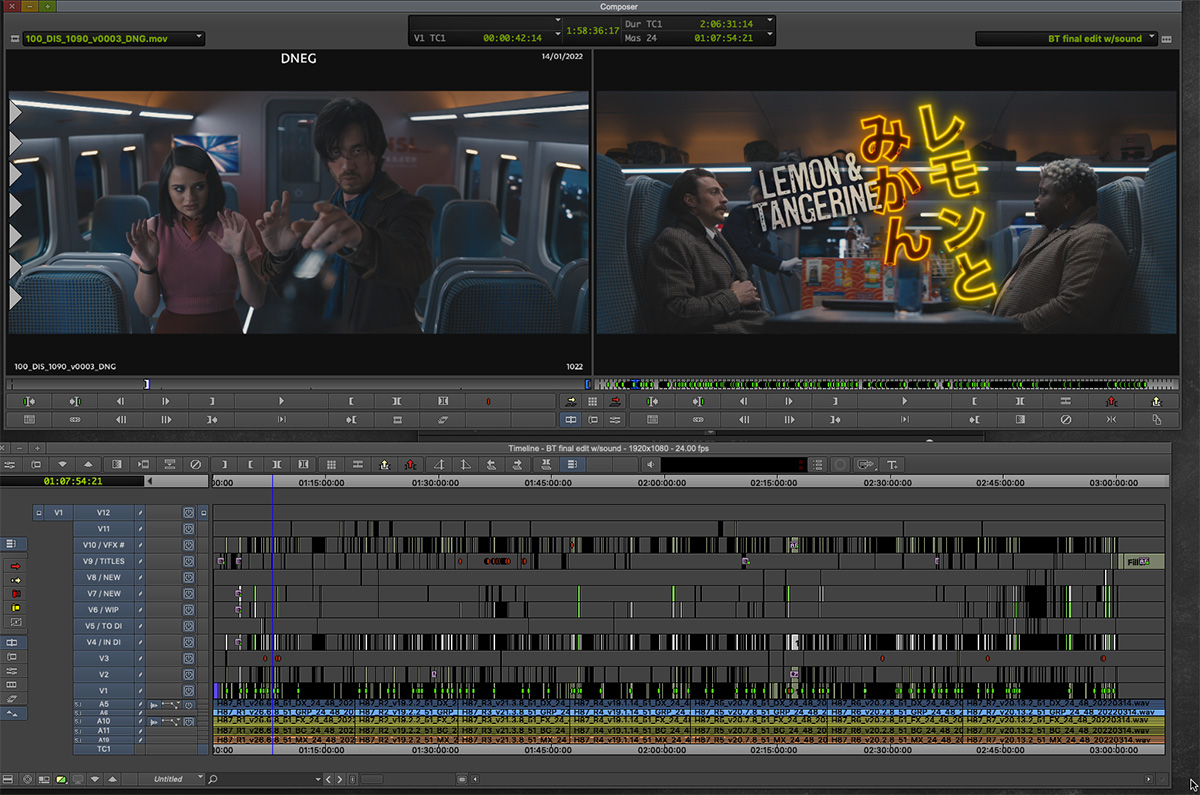

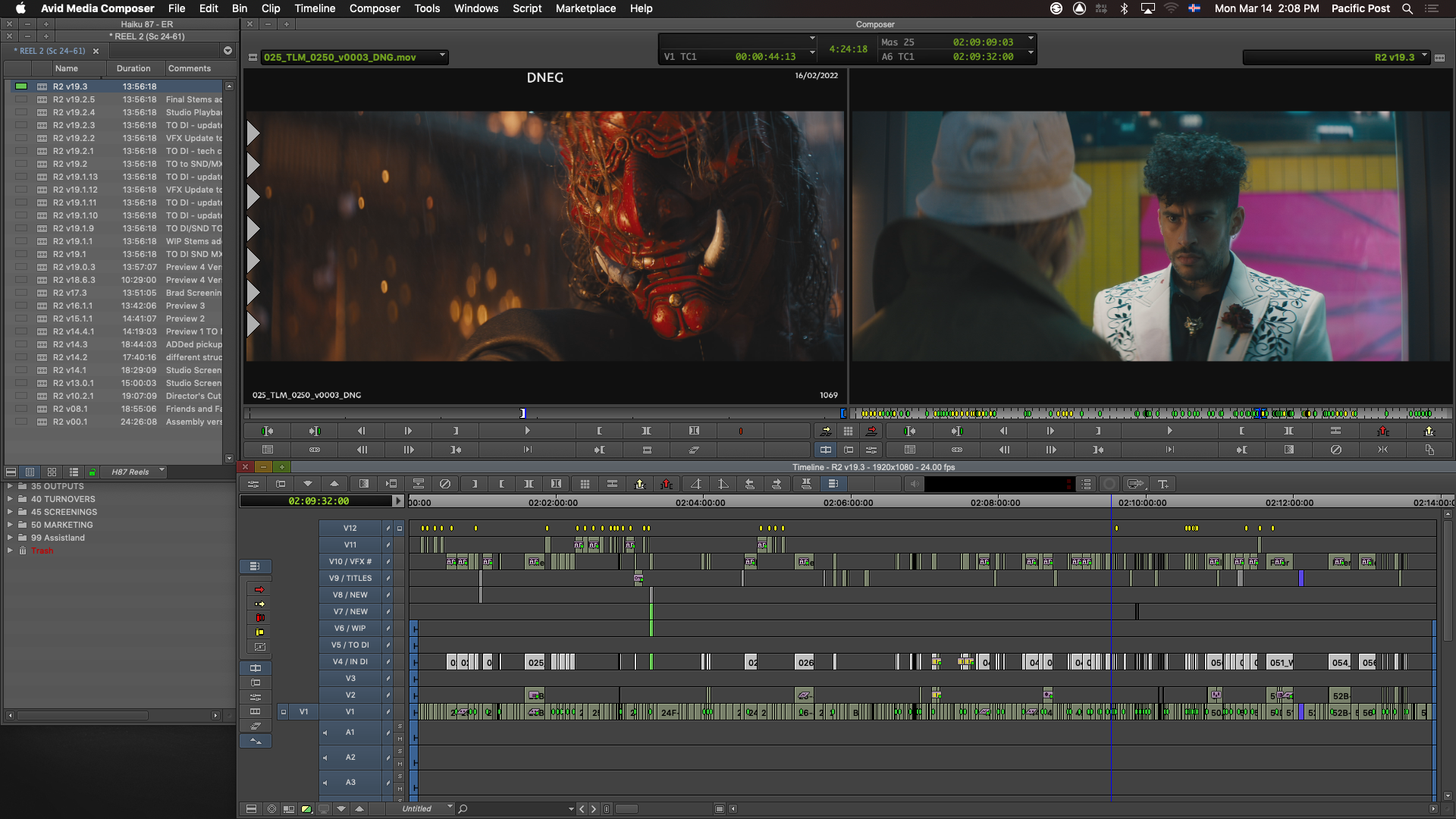

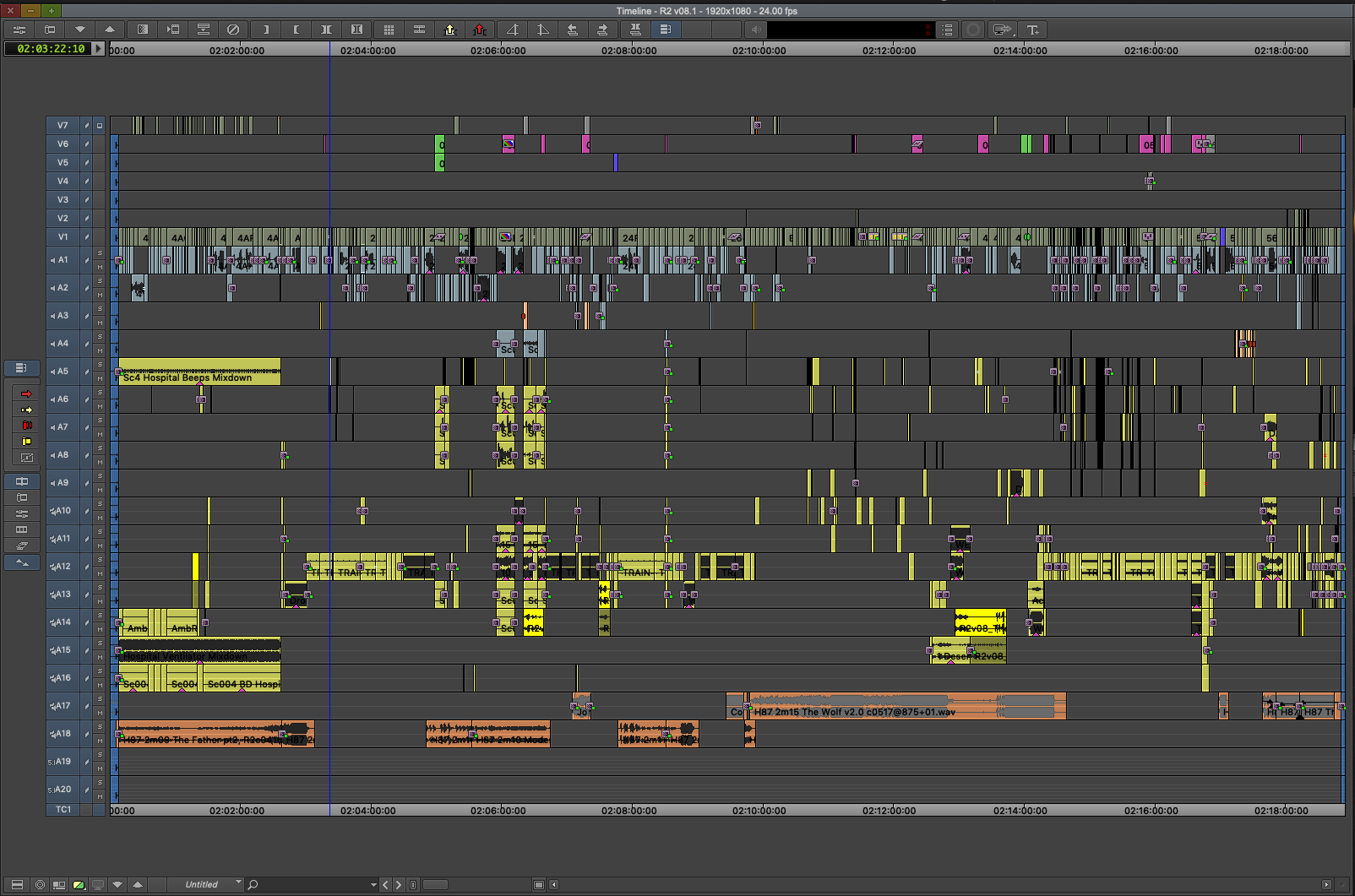

Avid Timeline screenshot of the entire film. There are only a few audio tracks with no edits, because these are the final audio tracks returned from the sound team. Note the difference between this timeline and the other timelines in the article where there are more audio tracks and you can see the sound edits.

Can we talk about breaking the 180 rule? I've had to do it but then I watched it on screen, and it worked.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I feel everyone who makes movies needs to know about this rule. It's extremely important but sometimes it's okay to break it. It depends on the material, what's happening, what's being said, what's being done. You have to be aware that you are breaking this rule, and you have to be aware that it works. You don't do it if it doesn't work.

Most of the time, when you're inside the car, which is where the conversation takes place, you want to be pointed toward the windows. The camera has to be on that side, but then you cut to the outside of the train and that breaks the 180, but it's almost a change of location.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It also happens often in fight choreography that we break that 180 rule. If you find the correct point in the movement, it's going to be fine. Just be aware. Know the rule. Be aware of it. The rules are there to be broken, but you have to know them.

Tell me a little bit about the difference between styles of fight choreography because this is different from John Wick, don't you think?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It absolutely is. The editing is always governed by the choreography and the shooting of it. You can’t do anything about the material you get. We had massive fun with all the fight choreography, which was extremely different. For example, the quiet car fight. How do you fight in a quiet car? We tried everything from taking the sound completely out and then we felt it was a bit empty. What gave us so much creative freedom is the film is set in a no man's land. It's set in Japan, on a train from Tokyo to Kyoto, but it's a no man's land. It has nothing to do with reality. The colors, the scenario, everything is like a parallel world. It gave us a lot of creative freedom. You have to believe to enjoy this movie, it's not a documentary. I think it's sad that we get stuck in documentary land when we're making movies and nothing connects them to reality.

That's an interesting idea. When you're using that, you're saying there are certain realities that you don't feel are important?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: If a guy is falling off a tank, does it have to be real? If he falls faster and it's cooler, let him fall faster. Go with cool. I'm just saying that there's freedom and joy in not having to obey all of the rules of logic.

I agree. One thing that I do feel that you did obey truthfully is the characters. Talk to me about finding those performances that feel real.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I think it's important to make them consistent. Amazing actors, they're all superstars, great performances, Lemon and Tangerine, a lot of ad lib, which was good. You have to think, who is this character? Would he do that? Would he say that? Be critical the whole way, try to understand that character and get closer to him, and then it's performances. It's a lot of work, but it's so rewarding.

Talk to me about the difficulties or what you needed to do to be able to keep certain characters alive. You've got this Brad Pitt character, Ladybug, who is critical, but as you mentioned, it's also critical to keep alive the Japanese father and son.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: We were very much aware that the Japanese father and son are the ones who have an arc in the story. That's why we open on the hospital. It's their story. At the same time, you have Ladybug being the main star of the movie. He has such a weight on the story. That's why I loved going from the hospital to him walking on the street. It's like all TV shows. Here's the crime. Here's the hero or the police. Ladybug is not a white savior. He's a dork, really. He doesn't save anyone.

We've talked about fight scenes before but you've always given tremendous credit to the choreographers and to the stunt people that do these. Can you talk a little bit about how you even manage some of these fights? How much of that is scripted out step by step?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Everything. It's a health hazard if it isn't choreographed to pieces. Every setup is thought of, and then you have to piece it together. A lot of the time, you have previz that the stunt team use as a blueprint where they actually shoot the stunt, just the stunt men. What I then do when I get this is I piece it together, and then I just watch it 300 times. I would do it backward, and sometimes without sound, just to try to feel. For me, it's like carving layers at a time.

Is there something for you to guide you? Do you have storyboards?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: It varies. We usually have either stunts or storyboards. Sometimes we get a minor fight and we don't have anything except what they shot, but it's the same. I think they should get an Oscar category, and I'm very proud of them.

Wasn’t Leitch a stunt person before he directed?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: He was a Brad Pitt stunt double. Now he's directing him. That's one of the reasons why both David and Chad Stahelski do such amazing action movies because this is where they grew up. What amazes me about David is just how well-versed he is in film history. He burns for cinema. Cinema is everything. I love that. A lot of our time is just talking about characters, talking about the story. That's all we talk about.

So much of what we do is not in the timeline.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I sometimes feel like at least 70% of my work is talking. This is a creative process. I just had the best first in the world, Nick Ellsberg, who ran the show, and I love him for it. He just got us through the pandemic with all kinds of software and magic. I was editing for almost half a year in Iceland, so he was able to sync us all up with Resilio and some other software so it's almost as if we were all working from a Nexus. He's not only a great first, but he's also a very talented actor, so he did the first pass of the bad guy calling Lemon and Tangerine and it ended up in the final version because it was so good.

Other than technical, what else was he helping with? What else was he managing?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: He was the captain of the ship. COVID put a dent in all our schedules and routines. I first met Nick when we had the first studio screening because we were all working from home and between countries.

How did you hire him?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I inherited him. I was finishing Shang-Chi and The Legend of The Ten Rings when Bullet Train started shooting, and Evan Schiff, who is an editor, helped get started while I was finishing Shang-Chi and Nick was his second. My first was still on Shang-Chi because we thought it was really rude to leave both of us and walk out. We didn't walk out. He felt he should stay behind and finish it, and so I needed a first. Nick was there as a second and I grabbed him.

From your perspective, what else does a first assistant do other than the technical stuff? How much are they managing your time or helping you realize what has to get done next? Or is it the other way around?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I just disappear into what I'm doing. It's a very internal process for me so I just disappear into myself when I'm with the team. I really get sucked into the work I'm doing but I wouldn't expect my first to manage me. I wouldn't do that. Nick is my first on Bullet Train, but my go-to first. We have probably a 12-year-old relationship. We try to work together as much as possible is Matt Absher. He knows all my shortcomings. I have such a respect for firsts because they basically run the ship, and it's a huge ship. There are so many balls in the air and you need very specific skill sets for it.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I think it's just honesty, problem-solving, and being positive. I find that extremely important. We're not here to get mad, like just, oh, we have a problem. It's a very close-knitted community. I miss that community because just having discussions with your team's important. I trust no one like Matt to look at my stuff and say, “What's this? Do you like it?” Sometimes I'm doing pretty drastic things. If it is cutting out stuff, it's like a dialogue massacre. It's correct in the script but this is the language of the movies where a whole monologue can become a look. I think that's an important part of having a first, just having this creative support because we're all working on the same story, even if we all need to have different skill sets.

You mentioned positivity is important to have in a first. What about that positivity between you and your director?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: I think it's essential. Why shouldn't it be? We are privileged. We're telling a story. It's the best job possible for me. There's never negativity and we can have discussions, but there are never arguments. I was lucky. I wasn't in Iceland, I was living with producer Kelly McCormick and David Leitch, who is the director because I don't live in LA. So I just moved in with them. Sometimes I would say, “I tried something,” and then we would all go downstairs, watch it, talk about it, and sometimes it didn't make the movie. It was just to try out things. Then David has to decide what way he wants to go. I do think it's a part of the positivity to just to bring options.

Were you cutting in their house as well?

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Yeah. It was like a film commune. So cut during the day and popcorn and movies at night. It was a very good setup.

I've noticed that you've cut several shorts relatively recently. Tell me about the value of cutting those shorts and why you do them.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: You're usually working with new up-and-coming directors and I just feel that we all have so much to learn from each other. The main thing is I do want to want to support women in this business. So I try to do my due diligence. I just really enjoy it and because it's short, it's not going to take you a year. So it's easier to give your time. I think it's precious for me.

I always enjoy talking to you and hopefully, we'll get a chance to see each other again soon.

RONALDSDÓTTIR: Thank you, Steve.