Today on Art of the Cut, Oscar-winning editor Conrad Buff talks with us about Apple+’s feature film, Emancipation starring Will Smith.

Conrad has been on Art of the Cut twice before for American Assassin and The Huntsman: Winter’s War. Conrad’s work includes an Oscar nomination and ACE Eddie nomination for Terminator 2: Judgment Day, an ACE Eddie nomination for True Lies, and an Oscar win and an ACE Eddie win for Titanic. Other films include Rise of the Planet of the Apes, The Abyss, Spaceballs, and Training Day. He’s edited for Antoine Fuqua, M. Night Shyamalan, David Ayer, Denzel Washington, Tony Scott, and James Cameron, among others.

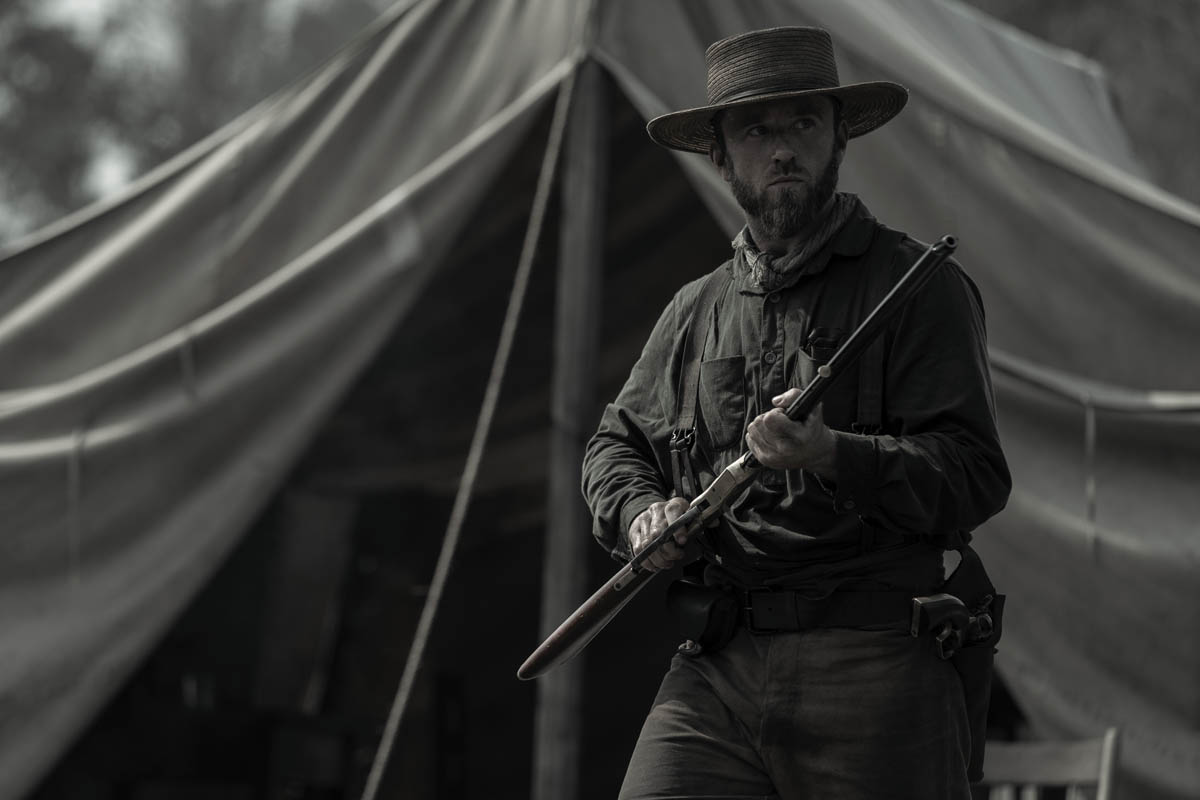

Oscar Winning editor Conrad Buff on editing Emancipation

How do you feel about developing a relationship with a new director? How much do you have to adapt to the way they work?I think there's always a lot of getting used to it, and that's possibly why I haven't worked with anyone else lately. I haven't wanted to win the trust of someone new, and honestly, to some degree, I'm surprised that I'm still doing this, but I love it, and fortunately, I'm able to still do it. I have such a lovely relationship with Antoine Fuqua, and it's hard to say no, so I'm not really seeking out other projects. It's unusual in that way.

I talked to Michael Kahn yesterday. He's in his 90s and still working with Steven Spielberg. You find those director-editor relationships, and you just want to keep them going.  Director Antoine Fuqua

Director Antoine Fuqua

It's just too lovely. It's so open, and communication is weirdly minimal. You're on the same wavelength, and it's a positive response. It's very freeing.

Let's talk about Emancipation.Talk to me about using that opening swamp montage to create a mood and setting up the audience for what they're about to see.That was the idea to basically sell the swamp as a character. That environment is so unique, and the images that were captured were so beautiful. I know it was somewhat reminiscent for Antoine ofTheShiningbecause, at the beginning, there was a series of shots that follow the car, and this has that same sort of persistent propulsion. The shots are very seductive, but they do set the tone. I think there was talk about not utilizing them in the beginning at one point and reserving them for later in the film when we leave the railroad camp and we reprise that same dark tone, but I think Antoine wanted to set the stage early, and if those shots had been eliminated, we would've been opening on a much more traditional shot over cotton fields across the top of workers in the fields. I think this is a stronger, more potent, more aggressive, and tonally disconcerting imagery.

One of the other obvious things that I would love to talk about is the use of color and contrast. Did the dailies colorist give you essentially what you were looking at in the final film?

What you saw in the finished film is very close to what I was receiving. Bob Richardson and Rob Legato both collaborated and worked on how to define the look. It's basically monochromatic, and color would've probably been distracting. There's something, particularly for the period, photographically more appropriate, but I was not party to any of those decisions. It was up to Antoine and Bob Richardson.

Talk to me about the choices in the montage after he leaves his family. There's a lovely montage that gives you a feeling of where he's going and where he's going to be. Talk to me about how long that montage was and how you decide the length when there's no dialogue to drive it and also about the use of slow-mo.One of the wonderful things for me, editorially, is the many opportunities, particularly in the second act where there's an absence of dialogue. In certain areas, it's more documentary-like; I have to ask myself, “How do I want to construct this? How do I wanna tell this story?” For me, that was some of the most fun but also the most challenging, particularly once they escaped from the railroad camp. I think it applies more to the second act, where that was the biggest difficulty for me in finding the right balance. I loved the fact that there's very little dialogue; it was liberating.

It sounds like it's freeing more than challenging.

It is freeing. I constructed this area where Peter's being pursued so we're following him, we're following his nemesis, Mr. Fassel, and then there's the family as well. Trying to find the right balance of those three ingredients was the trickiest part of the film. How long to stay with any one character? The first cut, that area particularly, was just fat. It was not as interesting as it could be. It lacked a certain tension and propulsion, so that took some manipulation.

When you had a fat cut and something wasn't quite as propulsive as you would like, what did you do to get to a point where you were happy?Primarily pruning, trying to distill the essence of each one of those beats. There were many moments within that area when I had huge amounts of material. For example, the paddling of the dugout through the swamp and Fassel tracking in various different environments. The family side in terms of the individual scenes was very straightforward but where did they program into this construction? That was the trick. It was experimentation; it was trial and error.

When you were trying to decide when to cut to, for example, the family, was it more about how long you've been someplace than any specific juxtaposition of emotion?

There were times when we wanted to keep the family alive. For instance, there's a moment when he is in a mosquito-infested area, and he's applying mud to his body and we came up with the idea to see what he's longing for, what he's imagining. There was a beautiful cut of his hand on her foot, cleansing her foot, which we saw at the beginning of the film. So there were things like that that were editorial inventions. I also liked the moment when he secured the honey from that tree and canoes away where he sits in the middle of the lake. It's peaceful, absorbing, nature, God, I think he's appreciating being alive. It's a very still, quiet moment and a nice contrast to a lot of the chase action beats.

A moment I remember being powerful is when Peter is attacked in the swamp, and as the attack finishes, it cuts to his wife waking up from a nightmare almost. It seemed to connect them physically. This very emotional moment for Peter to this very emotional moment with his wife.That was designed in the script, on the page for sure, but she does a lovely monologue there. There's no reason to cut, and I felt that way with Ben Foster (Fassel) around the campfire explaining his history. I wanted things to breathe - the performances - which are so damn good. The only reason to cut in that instance with Ben was anxiety developing on the black bountyhunter's suspicion of the white one worrying, but other than that, let Ben do his thing and the same for Will Smith in many places. It was beautiful, and I wanted to let it breathe.

There are plenty of fast-paced moments, but they're both so focused and dialed into their characters. No need for any artificial construction on my part. They didn't need my help; it was beautifully performed.

Talk to me about the big battle scene at the end. You mentioned that it was surprisingly easier to edit than you thought it would be.

Talk to me about the big battle scene at the end. You mentioned that it was surprisingly easier to edit than you thought it would be.

The whole sequence, I believe, was shot in about ten days, which to me is mind-blowing. The complexity of that whole sequence, just in terms of production, was incredible. To me, it was reminiscent ofBirth of a Nation.

I think second unit was pretty closely working with the main unit, so the material that I received was close together time-wise. I think I had 95% of the material to work with at the same time, which is unusual. It went together so easily for me.

I sent it to Antoine on PIX since I was in California and he was in Louisiana, and he shot back, “Don't change a frame!”[laughs]I had no communication with him about it, and I think there were some original designs for how certain camera moves would move, and we were going to do some visual effects connections, but I cut it differently than apparently what they were originally thinking, and I didn't realize it. I just did my thing, and then I got word, “It's great!” I think there was one little thing he wanted me to modify, but that's it.

How do you go about looking at the dailies to figure out how to construct a scene like that? Do you focus on select reels, or are you taking notes?

It depends on the situation. In the old days, when it was film, you would make a lot of notes because you had to study it and figure out how you were gonna construct and execute it because you didn't have time to mess around.

Obviously, in the non-linear digital world, you can mess around infinitely, but absolutely you have to look at all the material to understand so many different things about it and to appreciate what you have. If you don't see it all, you're not doing justice to what's been captured. Once I figure out how I'm going to start a scene, it all starts to magically come together. What do I want to see next? What do I need to see next? Digital editing is quite freeing, really.

How did you or your assistants organize it to be able to find what you were looking for?It's always pretty linear in terms of how the material comes in the order it's shot. It's all very logical, you become familiar with the material, you know where to access it, and if you're in love with one particular area but you're finding something isn't working, You can go back and refresh your memory of what's happening with that beat in other takes and ask yourself "Is that a superior moment? Should I incorporate that?" It's very easy to compare and look for the best material and distill it.

When you were watching your early assemblies, what were you finding, either with Antoine's opinion or your opinion of the macro-pacing of the film?

We never really had any discussions like that. It was really only that second act that was the most challenging. There was really only one entire scene that we dropped from the film, for instance. There was a scene with the wife who sacrificed her hand, and the buyer, who's going to take her away to another plantation, shows up to purchase her and take her away. We decided we didn't need that scene. The railroad camp spoke for itself, and the battle spoke for itself. It was really that whole chase that needed the most tuning.

A big part of that chase section is dialogue-free.Yes, it was great fun because it was dialogue-free, but also challenging; there was a discussion between Antoine and the studio, for instance, on keeping specifics things like when he is climbing to get the honey and Antoine said, “I want to retain it.” and the studio was very cool about giving him the cut that he was after. We actually only did one preview for this film up in Chicago.

What do you learn from a screening like that? How did it feel to see it with an audience?Oh, it's wonderful. It's a part of the process that I kind of love/hate. [laughs]Sometimes you learn there are clarity issues, but the other thing is you can frequently feel the audience and how they are reacting. Are they focused? Are people getting up and going to the restroom? You get a sense of an audience much in the same way if you're going to a theater to watch a play or film; you get a vibe.

There are also focus groups afterward, you can get some definition of what they didn't understand or what wasn't clear, but I don't like to do too many of them. One is good, two might be fine, but beyond that, not so much.

Where did you edit the film? Was the shooting all over the place?

Where did you edit the film? Was the shooting all over the place?

The shooting was completely in Louisiana. It started out in Georgia, and they had found some good locations, but then Georgia started messing around with voting rights, and Will and Antoine said, “We don't want to be shooting in this state and messing around with that kind of political nonsense.” Apple supported them to move the entire production to Louisiana.

While they were shooting in Louisiana, I was working from home in California. It was the first time I'd done an entire film at home other than a preview or final mixing.

Was Antoine in the room with you after he got done shooting?No, we utilized Evercast, and during the shooting period, I posted sequences to him on PIX and communicated a lot using texting which actually seemed to work well.

I've always preferred being on location because dropping by the set is like hanging out at the water cooler. There's information that you can pick up that is frequently helpful, but in this case, we weren't able to do that.

What's the benefit to the production of you being on set? Conrad Buff, ACE, in his home cutting room.

Conrad Buff, ACE, in his home cutting room.

Immediate feedback and communication with the director; second unit frequently being able to come to the cutting room; it's way better than being distant and remote.

With this film, there is a lot of Italian dialogue and subtitles, so I had two Italian assistants in addition to my American assistant who helped me with some of the subtleties of the performance that there's no way I'd appreciate; yes, I can understand some of the sentences, but it really helps, in this case, to have them guide me.

Talk to me about assistant editors. One, how you find a good one, and two, how you promote them and help them take the next steps in their career.I have an assistant, and I've worked with for quite a few years actually, Carole Kenneally. Much like my relationship with Antoine, she and I have a shorthand. I get spoiled, [laughs]things are organized and managed in a beautiful way, and I don't have to explain it to anyone. I'm insulated, and it's a luxury. The second assistant position frequently in the last few years has been quite variable. We've had different people at different times.

Years ago, when digital editing was beginning, a lot of us didn't know how to manage the systems; we could utilize them for editing but not the management of it all. I had a younger person in that role, and I realized what was lacking while they could manage it technically; there's so much more to that role of assistant editor of politics, how to manage a cutting room, how to communicate with producers, communicate with advertising and marketing.

It's a very complicated world, and because I grew up in film editing, I'm sorely lacking a lot of the knowledge required to do that job, so I give them great credit. It turns out that what I was looking for was maturity, somebody that knows how to manage those things in a positive way and maintain a balance; it's hard to find.

Was there a specific scene in this film that you either are really proud of or that was a real challenge for you to cut?

The scene I'm most proud of - and that I’ve mentioned before - is the one with Fassel's monologue around the campfire. It's subtle. It's balanced and on the surface, very simple looking. It's definitely one of my favorites.

Let's discussthe transition that you went through between cutting on film and cutting digitally. What do you remember of that and the difficulty or the joy and the freedom of it?The entire time I was in the Navy, I made documentary films. I made commercials when I came out for quite a few years as an editor, I always wondered what the technology would be that applies to editing. There were different attempts along the way to utilize tape-based systems that used multiple stacks of VHS tapes, but they were all so funky. None of them were ever attractive to me.

Eventually, I started working in feature films, and friends in the commercial world began using Avid. I thought I'd like to learn something about that, never assuming I'd apply it to film, so I took a class at USC in Avid, and lo and behold, the next film that came my way, the studio wanted me to use some tape-based linear system because they had expedited the post-production schedule and they thought that would help me. I said to them that I'd like to try something else, so the director, Roger Donaldson, and I went to Avid, and I demonstrated what it could do, and he was all for it. This was around 1993 or so, and I think there had only been a handful of films edited on Avid at the time so I then had to find an assistant that could manage it. I had a film assistant that I loved dearly, and I found Joel Negron, who at the time knew something about how to manage it.

In those days, I was using little optical drives, and I remember playing a car chase sequence for the filmThe Getawaythat Roger Donaldson had directed; I could only play about half the sequence for him, and then I'd have to stop, put in the optical disc for the other material and play the second half, but he was game. It's funny; at the time, I thought, "That'll be the last time I ever get to use it." But lo and behold,True Liespopped up, and I said to Jim Cameron, "Look at this," and since he is interested in technology, he allowed us to use it. So Mark Goldblatt, Richard Harris, and I used it on that film and never went back to film editing after that.

Amazing. Conrad, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it.Oh, you're welcome. Thank you!