Today on Art of the Cut, Bob Ducsay, ACE, discusses his work on Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery.

I’ve spoken to Bob before. His credits are lengthy and include The Mummy, Van Helsing, Jack and the Giant Slayer, and Godzilla. He has worked with Rian Johnson since Looper (2012), also on Johnson’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi, and on their previous film, Knives Out, for which he was nominated for an ACE Eddie. They’ve also worked together on the TV series Poker Face on Peacock TV.

Bob Ducsay discusses editing Rian Johnsons Glass Onion A Knives Out Mystery

Thank you so much for joining me, Bob. It's great to talk to you.Yeah, it’s great to speak to you as well. It's a pleasure.

Before Looper — which was, I think, your first film with director Rian Johnson — he was his own editor. Talk to me about working with a guy that is used to editing for himself.As you accurately point out, I was the first guy Rian had to deal with as a full-time editor. He and I talked about this recently ‘cause I've never spoken to him about it at any length.

I could have guessed based on knowing him really well how he felt about it, but I asked him if it was difficult (I thought it might have been). It was to start out because it's a detail-oriented task. A lot of directors are micromanagers, and editors are micromanagers. So to have that sort of collision, it isn't really surprising to me that he said that he had found it difficult to start.

Ultimately I wasn't particularly worried about it. Because I thought that we would be able to find a way that made him comfortable, and in fact, we were. It got there pretty quickly.

I think it was harder for him when we were shooting on location because I think he dreaded coming over and looking at cut material. It was just so foreign to him even to have that happen. When he was cutting his own movies, he was doing it once they were shot. I don't think he really like doing that very much. Then we got into screening the movie, and soon after that, honestly, it became much easier for him. He realized that this could be beneficial to him to have somebody else that's got a different point of view at times. You’re still there to serve the vision of the director in the movie. We got into a really good groove by the end of the movie and then what's really great is we've worked together for over a decade now. We've done four movies. He's got a new television series that starts on Peacock after the first of the year called Poker Face. I did a couple of episodes that he directed for that. And that adds up to about a feature film's worth of stuff. We’ve done the equivalent of five feature films.

Daniel Craig and Rian Johnson in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Daniel Craig and Rian Johnson in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

What's happened over the years, of course, is not only that we've gotten to know each other much better personally, which is obviously beneficial ultimately because you know each other really well, but also professionally too, because we've found a really great way to work together.

I consider it my job to understand what the director is looking for, not necessarily even just specifically for the movie we're working on, but just generally what their point of view is on how editing works and what it means to their film and also just stylistically and their point of view on storytelling.

If you start off with that in mind, you have to sort of push your own ego aside and your own particulars aside and hone in on really enhancing and delivering on the vision that the director has. Rian and I align very well, just naturally, but I think over time, it's just gotten better and better because you can get down into the tiniest of things.

There are times when I go, yeah, he's not gonna like this, and I do it anyway because, I mean, I won't do it because I know that there's zero chance that he's gonna like it. But I might instinctively feel like this is not gonna be something that he's necessarily gonna go for.

I think everybody has to do that because that's really bringing more to it. Sometimes the way it goes over is like, this is great, and sometimes it's like, I really didn't see it this way, here's how I saw it. You adjust to that, but that thing that you showed is still something the director saw. Sometimes we go back to it.

Time is really extraordinary when you're collaborating with somebody because you are able to get really in sync and understand not only what you can bring to it but also me understanding what the goal is.

Rian has a very strong point of view as a director, and what I mean by a strong point of view is not that he's not a good collaborator. Everybody he works with. He wants the big contribution, but he knows the story he's trying to tell. He knows thematically what he's trying to get across. He knows the style in which he's working very clearly. He's not unsure which any editor will tell you is your ideal director.

Absolutely. I'm interested in that point that you made that after four movies, you kind of know what he wants, but you don't always wanna deliver that necessarily. You could say, I know this is the way he wants it cut, but that's not providing input. That's not providing your editorial feedback by just giving him what you think he wants.Absolutely, and the thing is, any director Rian in particular, if he says to me I don't like this, this is not how I saw it. I don't think it's as good as how I saw it. There's no loss in that.

If every time I did something like this, he always rejected it, I'm sure that I wouldn't keep trying it. Right? But the thing is, one of the things about editing is your taste and your judgment are the whole deal.

It doesn't mean that you don't make adjustments from your own point of view. Because, again, for me, it's extremely clear. There are two people I'm working for on the movie. One is the director, and the other one is the movie.

If you deliver a great movie, everybody's gonna be happy. You have to stay in service of that. As long as that's your North Star, and as long as that's the thing that you always have in your mind because I have an ego, I wanna be right about things. I mean, it's like anybody else. I think it's important to have an ego just in general because you have to have something to bring to it, but you have to push that into the background when it gets in the way because again the movie is the thing and you really have to service that.

You sort of find this way of providing service, providing enhancement, doing something for the movie. It's no different than the screenplay. Then you cast actors. The actors are bringing an interpretation, but it all has to be within the vision of the director.

Is there an advantage or even a disadvantage to Rian having written this? Directors don't always write their own material.My experience has been typical of what you'd think it would be because you'd think that they'd be super precious with their stuff. And my experience has been they're not. And, uh, the fact that they created it from the ground up is an enormous advantage because they're really bringing something to life.

To cut something that you wrote seemed to be more difficult, but at least in the writer-directors I've worked with, it's not the case. I think there are only advantages. I don't think there's any disadvantage.

The fact that you have the writer there when you have an idea: "Hey, you know what we need? We need…." They’re there to deliver the words or the idea to fix it, which is really great.

Kate Hudson, Daniel Craig, Leslie Odom Jr., and Jessica Henwick in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Kate Hudson, Daniel Craig, Leslie Odom Jr., and Jessica Henwick in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

We shot the movie in Greece and did stage work in Belgrade, Serbia. The whole movie was made in Europe, and yes, I was there.

Someone just said to me, “It must have been unbelievable to be in Greece!" and I said, “Yeah, I traded this dark, tiny cutting room in Los Angeles for a dark, tiny cutting room in Greece.” I'm only half kidding because obviously, it was very enjoyable being in Greece and also frankly in Belgrade, which was a lovely city and a great place to work.

With Rian, to a certain degree, because of the relationship of editing to writing, it's something that he really understands the power of and the necessity and what we can do. Especially over the years, as we've become great collaborators, I think the value of my being around is particularly potent because I personally find the production part of the movie far and away the most difficult part of my task. Sometimes I find it oppressively difficult.

I don't find my job naturally easy. When we're shooting, it's even a bit worse for me because the first cut is really important to me. I want to be endlessly thorough with the material because once I've done that, I feel that now we're going to shape this in a direction that is serving the end goal of a great movie — serving the point of view of the director.

I want to make sure that I've left no stone unturned. I spend a lot of time with the material early on. There's a real goal to service the production in a couple of ways so the department heads can see how things are progressing, where we have trouble, and, even more importantly, for Rian to see if there are any adjustments that need to be made, whether it's in how a character is working or if there are any storytelling problems or that sort of thing.

The other issue is that practically speaking, it is much cheaper, more efficient, et cetera if you are missing something. If you're missing a closeup or if you have a little problem that you need an additional shot to make something work, you need some insert that people weren't thinking about, and it's not on the schedule. It's much easier and better to get those things before you leave. We really endeavor to have nothing to do by the time we finish shooting. This is of particular importance to both Rian and Ram, his producer.

We've done really well in the four movies that we've done together where there's been very, very little additional photography. Looper had one day. I don't think Knives Out, or Glass Onion had a full day of anything. I think we did a couple of inserts in the office, and even Last Jedi was only three or four days of additional photography.

We've done really well with that. I think that's to the benefit of the production because to start the whole machine again is really, really expensive. There's a whole litany of things that you benefit from being on location. It's hard to beat that face-to-face interaction.

It's easy to come by the cutting room. It's easy if the art director needs to come by or the cameraman needs to come by to see something. I did not love working from home. I really didn't enjoy all the remote work. I think that you get a lot of benefits from face-to-face type interactions, especially with the director.

How close were you to actually being on set?It varies on the movie. Last Jedi was mainly a studio movie. There are locations, obviously. On Glass Onion, I was rarely on the set. Most of that had to do with COVID. Rian came by editorial at wrap and probably came by three days a week, something along those lines. We had really good interaction. We'd spend a few hours together and go through the week's work and see how we were doing.

Dave Bautista and Madelyn Cline in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Dave Bautista and Madelyn Cline in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

It's a really interesting way of working if you're able to do that. You can have the most immediate interaction possible.

I've actually done that on a couple of movies for very particular reasons. You could send one of the assistants over to the set and get some stuff off of the videotap and plug that in. That part seems to be a little bit too extreme to me.

There's a fun little introduction in Glass Onion where all the characters get this little puzzle box that they have to solve. How did you keep that moving while also showing the complexity of the puzzle?I love that sequence you're talking about. It's basically the very opening of the movie. It has this puzzle box in it, which is really organic to a murder mystery, and all of the characters. These very vivid, wonderful characters are introduced.

The puzzle box is presented in a split-screen structure which is really fun because it's something cinema can do. You can be in multiple locations simultaneously. It's a bit of an old-timey technique, in a way. It's not really all that popular in current films, but it's extremely effective and really fun.

You could take any finished movie, put it in front of a preview audience, and say, “How was the pace of the movie? Was it just right? Slow in parts?” And I think that you'd hear “Slow in parts.” Then if you ask the audience, “Where?” they would say, “The beginning.” It's just the nature of the first act sometimes that you're kind of getting it going. The movie hasn't done all the things that the movie's gonna do. Both Knives Out and Glass Onion were no exception to that.

One of the things, particularly in Glass Onion, is the characters just leap off the screen because they're so well designed by Rian. You start with a great deal of interest, which is endlessly helpful for keeping the audience engaged. Plus, you insert the structure of the puzzle box and the split screens, and the fact that there's a lot of comedy in that. I think the audience gives us a bit of a break as we give them a lot of information and set up characters that they're going to join on this big adventure.

It's still a challenge to keep it moving fast enough because the audience just inherently wants to get on with the movie, and in the case of Glass Onion (if you're seeing a murder mystery), you need to get onto the somebody being murdered.

Because of that, we were aware that we really needed to keep it moving. It’s a matter of making choices with character. The tiniest things are meaningful to the characters (and the audience ultimately), and it's also a little bit fragile. You have to be very careful. You have to be very disciplined as you're aware of pace. You also have to be aware that you're giving the audience all the things that they're going to need to take with them on this journey. The split-screen added a lot of complications in making all of that work, but I think the end result is really satisfying and really a lot of fun.

.jpg) Edward Norton, Daniel Craig, and Madelyn Cline in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Edward Norton, Daniel Craig, and Madelyn Cline in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

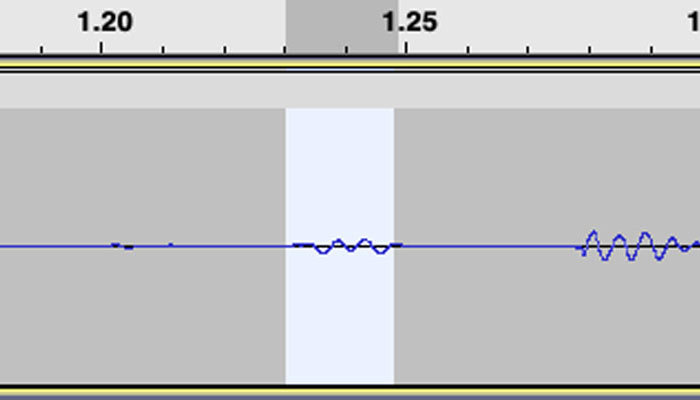

It is complicated because you're using multiple layers of things. You have to get everything in sync and make sure that all of those things are working well. Essentially they work as wipes that lead multiple characters on the screen. I worked all that out on the Avid. I'd work out all the timing of how these things would work. I did it very crudely.

I'm working with this incredible visual effects editor, Vaughn Bien. Vaughn was on the show. I turned the material over to him with all of the timings and how it worked. He just went to town and really developed these really fun shapes. There were a couple of things that I knew what Rian was expecting, but a lot of the things we just went off, and Vaughn did his thing.

When I showed Rian the movie the first time — I felt I'd get a lot of feedback on all of that — all of the timings, the way the box has worked, the shapes, and all that. He just loved it, which was great and a real testament to Bien’s beautiful work.

I determined the timings and how everything moved in and out in an extremely crude way, but then it was polished. 90% of the way those boxes move is the first take on it because he just nailed a really great idea.

It's important to surround yourself with the best people you possibly can because they have a way of making you look good. I always figure as many people as I can have in my cutting room who want my job. That's what I want. I want as many people who just want to chop my head off and take that job because they're inspired to do work to get them to where they want to go.

There's a big turn in the middle of the film. How did you pull the audience through that? I knew where I was going, but I could see that you could get lost.That reset messes with a lot of things at the exact same time, and it changes time. It changes all kinds of things. If you read the script, you think, “Wait! What?”

When we put the movie together, we were always aware that this was going to be a potential problem area. We hoped that there wouldn't be any issues at all, but we're asking the audience to deal with a lot all at one time.

Sure enough, when we screened the movie (doing our initial friends and family screenings), the majority of the audience had no issue whatsoever. It worked the way that it was supposed to. But for some portion of the audience, it was confusing for them. We really dug down deep when we talked to people who were confused by it to find out where it made sense to them, and it was longer than we found tolerable. The problem with having an audience confused for too long is that they're disengaged from the movie. They're thinking, “I don't understand what's going on.” They're not paying attention to the movie anymore. They're just trying to figure it out.

You want to feel like you're in good hands. So you want to feel like, “I don't know exactly what just happened, but I'm sure it's all gonna work out.” But we felt that it was maybe a little bit too much. Some portion of the audience was confused enough, so we had to embark on a series of changes in that sequence. None of them were monumental on the surface, but they were definitely significant items, and then a couple of small items that we did to correct the situation.

We got ourselves to a point where the sequence was not a problem any longer. They were getting on board where we hoped that they would get on board. That's one of the challenges in cutting a movie: when you encounter something like this, you have to identify the problem. Why exactly is the audience getting confused here? Then hopefully, come up with a solution to solve it. I think we did.

Kate Hudson, Kathryn Hahn, and Leslie Odom Jr. in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Kate Hudson, Kathryn Hahn, and Leslie Odom Jr. in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

It was music, it was ADR. It was rhyming it visually with the beginning of the film. The hope was that the audience would understand we are doing something big. We are resetting things. It seemed to work like gangbusters.

When you say “rhyming it visually,” do you mean the door knock that happens at the beginning of the film, and then you have the same shot to start the reset?Yes. A door knocking, coming out of black.

Repeating that helped the audience?You can't know exactly the amount of impact each of these things had, but each of these things had enough impact to solve the problem.

It's a huge cast with a lot of big stars. Talk about keeping that many characters and storylines alive. Or is that just a function of the script?It's actually one of the most exciting things about doing ensemble movies. This was true of Knives Out and, to a similar extent, in Glass Onion. It's absolutely wonderful. The cast is incredible, from top to tail. They're all perfectly cast and a great deal of fun, but the trick with an ensemble movie is you want to make sure that everything stays in balance. You have to make sure that everyone is being given their due. It's sort of like you're making a nice meal. The cast is giving you all these incredible ingredients. It's all so delicious, and you have to find a way to combine them all so that you can taste all the flavors.

Within that, some characters are more important than others in a particular scene. A scene might be more from this character's point of view. You have to pay attention to that. I think the discipline that's required is the ability to say, “We are going to take out this thing that's great, and that's working, and that the audience laughs at. We're going to take it out in service of the movie as a whole because it makes the balance of the scene wrong.”

There's a scene we call the disruptor scene. The entire cast is together outside of a pool house. It's probably seven, or eight pages in the script. It's a fairly involved long sequence. There were a number of things in that scene that were complete home runs. Huge laughs and really fun. Things that we really loved, but we cut them out because it was pushing the scene into this person's point of view, taking the focus off of this person. It's really hard to cut good things.

It happens anytime you're dealing with an ensemble cast, and you have a lot of characters together at the same time. You just have to be cognizant of making sure that you keep everything in balance.

Edward Norton, Kate Hudson, Daniel Craig, Kathryn Hahn, Dave Bautista, Leslie Odom Jr., Janelle Monáe, Madelyn Cline, and Jessica Henwick

Edward Norton, Kate Hudson, Daniel Craig, Kathryn Hahn, Dave Bautista, Leslie Odom Jr., Janelle Monáe, Madelyn Cline, and Jessica Henwick

Some shots are specific to telling a different point of view and even sometimes where you might see something that you didn't see before because you're now in a different position. Absolutely. There's specific photography for the flashbacks because the screenplay is this really intricate Swiss watch, especially when it comes to structure. But at the same time, that's not true across the board because there are still many, many choices that need to be made and material does get reused in the movie. There are a lot of choices that have to be made because those things aren't specifically designed — where you come back into a scene now that you're looking at it from another point of view, where you end the scene, and what material you have in the scene.

It's a requirement of the screenplay in a movie like this to solve many of the major structural issues. It isn't so simple that it's all just figured out. If you have scene 17, and then when it's reprised, it's scene 85, there are going to be slates for both 17 and 85 in that scene.

Then, of course, even though something might be designed, maybe using something from the original scene works better. So it becomes this issue you really just have to work your way through it and see what works best.

If you've seen the scene once, then the second time you see it, you don't have to show the whole thing.Correct. The idea is the audience is delighted to do it again. If you make it drudgery for the audience, then obviously, this is not going to work. You have to give them what they need. Sometimes they need more than you think. Sometimes they need a lot less. It's a big part of editing any movie, particularly when something has an involved structure like this murder mystery, it becomes even more of a challenge.

A lot of the success of these kinds of films is misdirection. You want to kind of mislead the audience, but you also have to show them the clues they need to be satisfied. Can you speak to what you do in editorial to help misdirect?Absolutely. Because you’re setting characters up, you want to make sure you've got some delicious reaction that looks suspicious. You wanna place it in just the right spot so that you know that the audience is noting that.

Part of what you're trying to do the whole way through is misdirect and hide. You're trying to do both with the audience. It's certainly part of the genre. It's really fun, but some of the suspicious closeups…they’re surprisingly effective.

Then you start second-guessing it, which is great too, because then you start thinking, “Maybe that's not really what they're reacting to. I'm being led down the wrong path,” which actually brings up a good point — something we put enormous effort into (it was way more of a thing in this movie than it was in Knives Out) — is being completely honest with the audience, or at least as much as we possibly could be, putting many clues in plain sight.

If somebody were to watch the movie a second time, you don't want them to feel like they were screwed over and lied to. You want them to be delighted by the fact that they missed something that was there. So we really got into pushing the envelope on those things. It's really quite extraordinary. I can't talk about any of them here cause we're trying to be spoiler free, but there are really some extraordinary things that are there in plain sight. You just don't know to look for them. I don't mean that it's something hidden in the background. I mean, it’s right out in the front. You just don't know to look for them, but there are some doozies in there. I really love it. I think if you watch the movie again, you'll see that we've really played it straight.

Janelle Monáe in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Janelle Monáe in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

I did. I cut movies on film. I cut on the original non-linear editing system, the Moviola. Early on, I thought, “There has to be a better way of doing this.” So I was really interested in the early non-linear editing systems. I did two low-budget movies on this Lucas film system called EditDroid. That was a laser-disc-based system. It had an extraordinary interface. It used a Sun Microsystems computer which was an incredibly powerful computer and UNIX operating system. You could network multiple systems together.

I cut a thing on Montage, and a buddy of mine, James Brewer, was an assistant at the time on LA Law. He called me up and said, "Hey, you gotta come over here and check this thing out. It's called an Avid." I looked at that thing, and I thought, “This is it. This is what I have to use.”

I wanted to get out of film as quickly as I possibly could, but I'm glad that I've been at it long enough to actually go through it because it's beautiful. There's something about the smell. You use grease pencils. You cut the actual physical work picture. You splice it together. There's something really wonderful about it.

I think the first movie I cut on AVID was in 1991. So I've been using Avid for a really long time. I'm grateful to be able to use this system because there are just so many things that it allows that you can never do on film. I'm really soundtrack-intensive. I cut in 5.1. We do all kinds of stuff with the soundtrack. You can temp in visual effects.

There used to be a system called a KEM, and you could maybe have two sound heads. They used to have these things called Juniors. You could connect a wire between the two of them, so you could have multiple KEMs running. Maybe you could put up a soundtrack or two. It wasn't like there was any automation or any mixing, so you'd have to live mix it. The soundtrack was basically a single track of dialogue, and if you had overlap, you just cut 'em off. The overlaps had to be sent out to a transfer place.

I don't think movies are made one bit better by cutting electronically. Not one bit. If you think about all of the great films that were made that were edited on film and some of the great achievements — movies like Apocalypse Now or Top Gun or The Fugitive — these massive, endlessly complex films. I'm glad I got to experience it because I know everything about it, but I'm also glad that we don't work that way anymore.

You're the second person this week that mentioned knowing somebody on LA Law, and that was how they learned about Avid.I don't even know what to say about that. Maybe LA Law was at the forefront. That is sort of funny.

Kate Hudson and Jessica Henwick in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

Kate Hudson and Jessica Henwick in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022)

If I had to like pick a sequence that I enjoyed doing the most, it’s when Blanc lays out the crime. First of all, Daniel's interpretation of the character of Benoit Blanc is absolutely hilarious. He's such a powerhouse actor. It was so much fun cause it has flashbacks which cinema does so well. In a 24th of a second, you've gone back a week, a month, centuries — and it has the whole crazy cast of characters there. It's just so much fun to put together because it's what the audience has been waiting for, and it's what I'm personally waiting for when I see a movie like this.

It’s Blanc at his Blancy-ist.

He's got to enjoy that character after years of Bond.I just think it's amazing that he's become this other great iconic character. He's so talented, the character is so much fun, and that accent is just the best.

Are we gonna see another Benoit Blanc movie?Absolutely. It is guaranteed you will see at least one more because Rian is in the process now of figuring out the next story.

Fantastic. Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it, Bob. It's been really fascinating finding out about this movie and your post process.Thanks so much, man. I really appreciate it. It was really fun talking to you.