Today on Art of the Cut, we speak with the editors of Gran Turismo - Colby Parker, Junior, ACE, Austyn Daines, and co-editor, Eric Freidenberg.

Colby’s been on Art of the Cut before for his work on Mile 22. Colby was nominated for an ACE Eddie for his work on Ant-Man. His other work includes Patriot’s Day, Deepwater Horizon, Lone Survivor, and Battleship.

Austyn has edited the feature film Demonic and the Travis Scott documentary, Look Mom, I can Fly.

Eric has cut features including Kandahar, and documentaries including The World of Thinking. He’s also cut TV including 30 for 30, 9-1-1, Unsolved Mysteries, and Chef’s Table. And he was an editor on the GT Academy TV series.

Art of the Cut: Gran Turismo

Did you get a tool chest of great racing sounds that you could use when you were doing your initial cut?DAINES: We definitely got a sound package at the very beginning. We had Charles Deenan on the film, who is really profound in commercials, and Neill [director, Neill Blomkamp] has worked with him in the past and he gave us a sound package to work for him. That wasn't for the whole film. I think we were using basically the same car sounds for all the races. We had three different sets of cars for each race. The car that sounded nothing like what it ended up sounding like was our LMP2 [Le Mans Prototype 2] in the Le Mans race. So once we finally got through the director's cut and started getting into the mix, when we actually got the LMP2 recorded, it was really special to hear. We had a lot of help from Conor [Burke] our first assistant, in doing the sound design, at least for the sequences I was involved in. He was stellar with sound design, so I think the intent was there and maintained throughout the whole process, but it just sounded beefier and had that really pro touch, once we got the sounds from Charles and also from Beau Borders, our Sound Effects mixer and Kevin O'Connell our other mixer.

In the races there are some great rhythmic editing — there are longer shots, you know, obviously they're going down a straightaway or coming around a corner or something — but then there are these are beautifully rhythmic, maybe eight frame cuts. I don't even know what they are. Did you cut that stuff with sound when you were cutting the visuals or did you cut on mute when you were doing those racing sequences with the great sound design?PARKER: All of that is done with sound. Maybe internally before we present, we'll put the cuts together. But as far as presenting and trying to get those past Neill for approval we always have sound design. We always try to make things sound professional as possible. There's no such thing as presenting a rough cut anymore. If you want something to live, you have to sell it. Just having done a lot of sports films and working with someone like Pete Berg, who really reacts well to cuts like that, I kind of learned the process of doing that rhythmic editing where you can't do it for too long either because, my audience will get desensitized, so it's about pacing and a little shot of adrenaline and then let the audience catch up.

FREIDENBERG: Beau Borders is a racecar driver himself, recreationally and super into it, and they went out and recorded a bunch. And there was some stuff that they put in later in the mix that was just extremely accurate: downshifts as we're coming into a corner, when they're braking — really specific stuff that I think helps a lot just selling the verisimilitude of the racing sequences. And then also they sent us this package of stylized sound effects. They’re at the opposite end of the spectrum: there were these sort of like whoosh-bang with an engine growl things that we ended up using a lot for the freeze frames. So it ended up being really cool hyper-stylized in moments and then super-realistic in others.

PARKER: I can't articulate it, so it'd be great for Eric to explain what we've started doing on the last couple of films is dedicated a few tracks that Eric would put a lot of these whoosh-bangs on. Can you talk about the RTAS [Real Time Audio Suite] track effects?

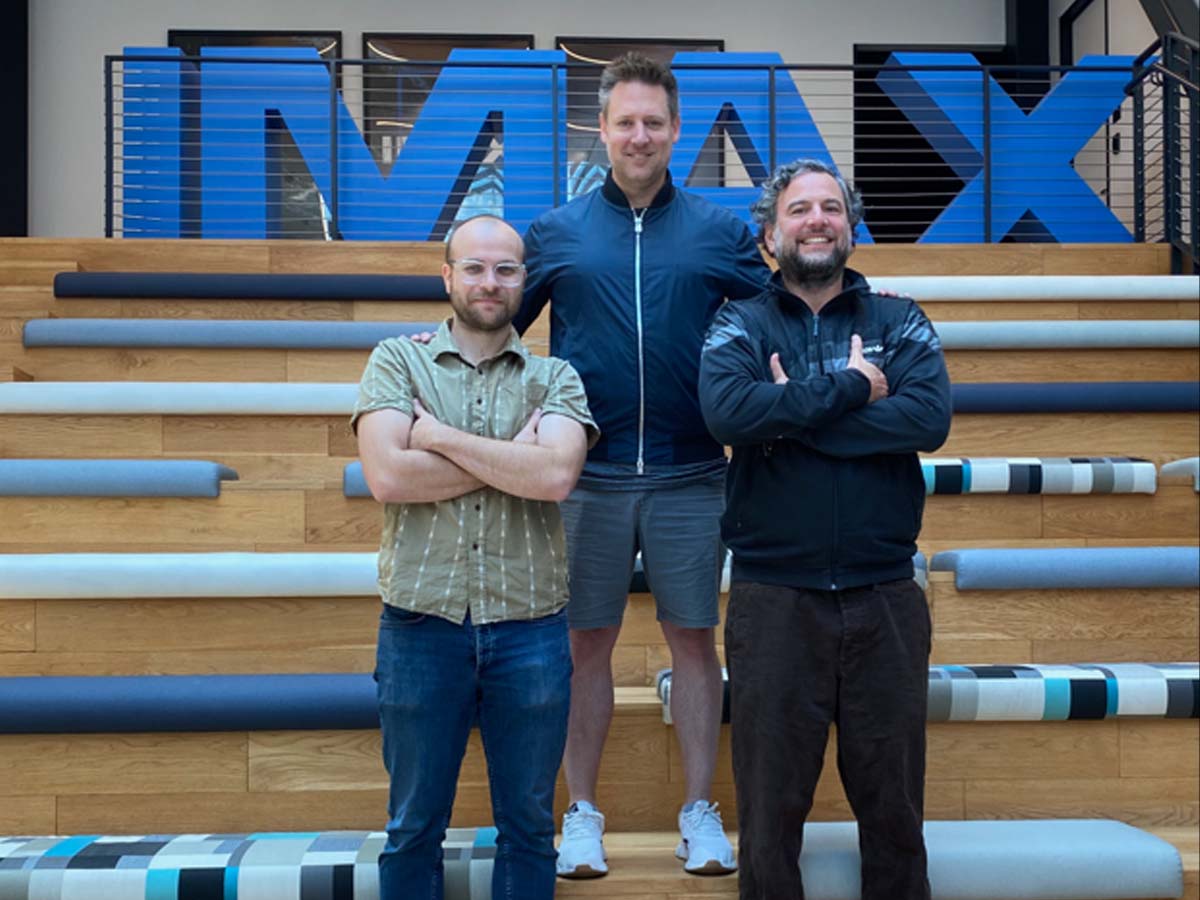

On the mix stage. Colby and Austyn, photo by Neill Blomkamp himself!

FREIDENBERG: They’re track-based effect inserts in the Avid and they just put different decays of D-verb — long reverb. I actually found out they hate them on the mix stage and they would curse me out because when you press stop they keep ringing out and one of them is like a minute long, so think they were losing their minds.

PARKER: One of the effects is called “Eric Long.” So at the mix they said, “You're Eric?” They were really mad.

FREIDENBERG: It’s a quick and easy way to manipulate and add ring-outs and reverb and style that we use all the time, both for music and sound effects.

DAINES: It was really huge for us, especially for me, because this is the first film in Avid that I've worked in. I come from Premiere and so when I came into the project, they had this already set up and I used it all the time. Like in every sequence: “Okay, I'm sold. This is a wonderful way to work.”

RTAS is allowing you to add an effect — not just to a clip in the track, but to the entire track — so that it rings past the end of the clip. I want to get back to the rhythm thing. When any of you are cutting those sequences with just real nice rhythm: gearshifts and foot pedals and inside shot of the engine for a few frames. When you're initially laying that and building that rhythm, do you have any sound at all?

Austyn Daines in his cutting room.

DAINES: The first pass, I'll probably do it without sound, especially on a scene like this and kind of get the picture working well. And then I usually don't have help from assistants doing sound design. I'm like very particular. But Conor was so talented with it, I would just pass it to Conor and he would take a pass with a sound and we’d talk about it and then he'd give it back to me and then I would adjust. So it was kind of like this dance. He would do a pass at the sound, I'd get it and kind of look at it refreshed and think, “Okay, well, maybe this shot needs to hold longer” or, “You know what? This is not holding the attention properly.” So it was definitely a dance with sound and those quick gear shifts: once I added sound to those moments, sometimes I would revisit and make it even punchier. But one term that I've learned on this project from Colby and Eric is…

PARKER: The burst cut.

DAINES: The burst cut! We kept on talking about the burst cut and those were really nice to add some quick adrenaline into a moment or a scene.

PARKER: Yeah, to echo that, this started from Pete Berg, who would always say “triple cut it” and then we termed it a “burst cut.” There's something about the boom, boom, boom — the triple cut or as I call it now, my cubist editing, where to that note, very rhythmic. A lot of times I'll do a cut like that and ask Eric for help with the sound because he's extremely talented with that and he always seems to elevate my cut when I ask Eric to help me with a little audio on some of these burst cuts. It's definitely a rhythmic trick that I find always works.

<>Colby with timeline.

To geek out on that further: do you find that in those little burst cuts that those three cuts are the same length or slightly different? Are they all about eight frames or are they a little longer than that?

<>Colby with timeline.

To geek out on that further: do you find that in those little burst cuts that those three cuts are the same length or slightly different? Are they all about eight frames or are they a little longer than that?

PARKER: Eight frames is the default for me on a wipe on an edge wipe or anything I do is usually eight frames is the default. And I stole that actually from Dan Lebenthal — peeking in his timeline. But each beast is its own animal because I've found that when I try and redo it, I wonder, “why doesn't it work?” The footage has to speak to you and you can see where it works, but it is usually two quick cuts and then the third cut is a little more elongated. So it's sort of a left-right combo and then a big punch.

Ba-Ba-BOOOM!DAINES: You kind of gave away the secret sauce of that third cut. I'm going to have to steal that. It's always a feel thing for me, so I'm happy that you broke it down.

I've worked with multiple editors before. You wonder how they pulled something off, so you go look at their timeline: “Okay, okay. I see what it is. Two even at eight frames and then another at about 12. Okay, I see why that works.” It might not work for you the next time, but at least it gives you an idea of how they're pulling something off.

Eric and Colby... well, Colby and Eric.

FREIDENBERG: Just to the question about cutting with or without sound: I listen to your podcast all the time and I'm always baffled and amazed when I hear editors talk about cutting an entire film without music or sound. It's a discipline that eludes me. Especially for these action sequences, I couldn’t imagine knowing how it feels without some kind of music and sound where it's going to be. We also have the luxury of really good production audio tracks married into the Avid. So it wasn't really that hard. Obviously, it’s not what we ended up using, but if we needed an engine rev or something, it was pretty easy to find something that was presentable just to be able to like feel it.

I wouldn't have thought the production sound was as good. Not saying anything about the production recordists but just because you’re in a moving race car. How good can the production sound be?DAINES: There are moments where you're trying to dig out what they're saying in the race car and you’re thinking, “I have no idea.”

FREIDENBERG: To Neill’s credit, he shot the dialogue while they're actually in a race car, so it's pretty loud. It also makes it really cool because the drivers are really struggling in a way that you can't really fake.

In the early GT Academy footage — by “GT Academy” for those who haven't seen the film, they bring the racers in to this Academy to actually learn how to drive race cars — and they called it the GT Academy. In that footage, there's an interesting time compression or almost a montage where David Harbor’s character gets into a helicopter to watch the racers. He's up there for a while and then it goes away from the racers and it comes back into the helicopter. It's not something that threw me, but it's something that I noticed. Was that multiple scenes that got compressed into a smaller time frame or was it scripted like that?

In the early GT Academy footage — by “GT Academy” for those who haven't seen the film, they bring the racers in to this Academy to actually learn how to drive race cars — and they called it the GT Academy. In that footage, there's an interesting time compression or almost a montage where David Harbor’s character gets into a helicopter to watch the racers. He's up there for a while and then it goes away from the racers and it comes back into the helicopter. It's not something that threw me, but it's something that I noticed. Was that multiple scenes that got compressed into a smaller time frame or was it scripted like that?

PARKER: It's conflating a bunch of different scenes. It's based on a true reality show, and Neill really shot it well, so basically we had a whole reality show to edit. So what happens is we edit all the scenes — each of us had a scene within that because we had a “next man up” mantra as the scenes come in and then it went into a reel. It happened to be that that reel was a reel I was working on and we just started conflating the scenes. You just shave it and whittle it down to the bone to see what you could get away with, because it was a sequence that was 45 minutes during the editor’s cut. So Neill said, “Let's cut this down.” Then to preserve different scenes you just start conflating it.

Audiences nowadays are able to process things and you can get away with truncating these scenes down and exposition still landing. As long as the pieces are in there, I think people store a bit of it and our audiences are sophisticated enough to get it. Obviously everything in the helicopter is shot as one big chunk, and then we move it around and turn it into a montage and just do the timejumps and see what we could get away with. And then speaking to Eric, who has done a lot of docu-series stuff. When I watch him work, I learned so much as far as his talent is really able to make a story out of footage that wasn't meant to be a story. He's very analytical, and so sometimes when I show scenes or bounce scenes off him, he'll be say, “This will have to be next in the story.” And I say, “Well, it wasn't shot like that.” He's say, “Yes, but this is how the story should be told.” You make up stuff or justify certain orders of scenes or sequences to help tell the story.

Avid Timeline of the editor's cut of Gran Turismo.

It's not just the helicopter. It's also when he takes the racers out running on the track and then they go away and they're in a race car and then they come back and they're running again. It's just a way to show that they keep doing the same thing over and over again, with compression of time.

Avid Timeline of the editor's cut of Gran Turismo.

It's not just the helicopter. It's also when he takes the racers out running on the track and then they go away and they're in a race car and then they come back and they're running again. It's just a way to show that they keep doing the same thing over and over again, with compression of time.

FREIDENBERG: I definitely give Colby a ton of credit on that scene because he cut it and recut it so many different times in so many different ways. From the very beginning we had that approximately half hour, 40 minute Academy sequence with each setup as its own scene. He would look at it all and say, “This is going to be six minutes tops. Hopefully, one hot piece of music. It's a montage.” He would pace around and say, “He's in a chopper. Then he's over there and then when he's back in the chopper,” the cubist approach to the burst cut applies also to a montage where it doesn't matter if it doesn't actually make sense, in some ways. It's the feeling and the audience will put it together and it actually feels better if you're bouncing around.

PARKER: Yeah, the non-linear approach makes the time go by quicker.

FREIDENBERG: Also finding the music is super key and I want to give a shout out to Colby's son Liam, who found a couple of the tracks that we used in that scene. He's a cool 23 year old and it really helps because he sort of is that demo. He's like one of those kids and I think he found three of those music cues that are just awesome.

.jpg)

PARKER: Now I’m going to have to pay him… Thanks Eric.

Is he going to put it on his IMDb page as “uncredited music supervisor” or something? They did the same thing in Oppenheimer when they went to go track down and recruit all the scientists, they would be with one scientist and then they would go off to find the next scientist, and then the next scene would be back with the previous scientist at a different moment. I think that's a common thing to do in editing, but it gives it a great pace, because you're not stuck in the same part of the story for so long and then move methodically down the path. You're jumping back and forth. I think it adds some energy. The training montage is all intercut. I'm assuming it wasn't scripted. It sounds like things got compressed.

PARKER: It's kind of a trailer. It feels like you're just cutting a trailer for one of these reality shows and then you want to start seeing people get eliminated and just tell the story. A lot of people definitely pointed out in earlier cuts it wasn't as linear as the final product. People asked, “Why was this guy eliminated and when was she eliminated?” So I had to kind of streamline it towards the end and start telling the story of people getting eliminated. Then we actually started to go a little bit more linear towards the end, but that can get boring and we don't need to harp on this. “When people get eliminated, I'm going to discipline myself to make this 30 seconds.” I gave myself a few rules to follow: “Let's just get through these people getting eliminated. It's not that big a deal.” It's not advancing the story per se. Then I just kind of fall back on my music video experience and try and literally get shots that look super cool and just keep it moving and find good music.

FREIDENBERG: I also give Neill a lot of credit. He responded really well to these sequences early on where we’d taken a lot of liberties and it wasn't exactly as scripted and he loved the “verging on chaos” beats and he would just say, “That was rad! Can you make it radder?”

Would you do that in your editor’s cut or was it further along in the process?PARKER: It's death to bore the director or whoever we’re presenting to. I learned from Pete Berg to try and really advance the story as fast as possible and tell the story in the quickest way possible and sort of the most subversive way as well. I want the director to say, “All right, you've gone too far. Pull back.” I never want them to say “make this cooler or make this crazy or it's got to move, man.” When they tell me, “All right, let's slow this down a bit and tell the story more,” it's like, okay, I can do that. That's no problem. So that's sort of my goal.

FREIDENBERG: We always cut a version of each scene with all the dialog as scripted, so we have that if we need to go back to that, we have it. Austyn also has a ton of polish, which I think if I'm surmising, it comes from commercials and being so tight in 30 seconds. So his scenes always came out of the oven really cooked already. There was not this idea that, “Oh, we're going to massage this and change it for months and months.” Everything came out looking almost done.

DAINES: Thanks, Eric. I appreciate that. I feel like that's also just from working with Neill I've worked with him for a number of years and we sent him cuts along the way as they're shooting in production, but when we were putting the editors cut together, Neill just likes to see what we think is going to work best. He wants to see your interpretation. He wants to see what you think will work best and use that as a starting point, so we put a lot of emphasis on that throughout the entire film.

When The Academy gets down to the final five racers there's a spoken intro. Maybe it's Orlando Bloom's character describing what's going to happen and you're actually seeing it happen as he's describing it. Was it cut for him to be on camera for that or was it designed for him to be voiceover through that section?

PARKER: In the script it's broken up as scenes. We embellished that and took it a lot further — sort of took that idea and ran with it. As a big fan of NFL Films growing up, they use a lot of voiceover and then slam in the action underneath the voice. So I've always learned that when you have a voiceover like that, you can get away with anything. And then the final thing is: I also have a background sort of in documentaries and commercials, and we call that see/say, where whatever they're saying we want to see it, and so I kind of adhere to the see/say gods as well when we have something like that and try and find things — whether it's a reach or not — that line up with what the VO is saying.

We talked a little bit about the close up shots — some of that kind of B-roll type footage that you used in some of those burst cuts — this is geeky, but were they inside or outside of scene bins? Did you have a bin of stuff from the inside of the engine? Here's Gearshifts. Here's pedals on the floor. Here's brakes.DAINES: They were organized as separate bins. And actually our visual effects supervisor, Victor Muller, who's incredible, he shot all those on set, but they're very specific to the car that Jann was driving. Like the GTR cars then there's an LMP2. So it was just trying to keep track of this steering wheel and this foot pedal is meant for this driver and this car. But we had bins of that. Then I just went through the scenes I was working on and made select reels of of those moments.

FREIDENBERG: The mechanical inserts that you're talking about where it looks like they've bisected the heart of a motor — I think they actually did that. They had to take the engines apart and they had this huge bin of that. I don't think it had a specific intention, so we kind of used it in lots of different places in different ways, and then when Neill watched it, I remember at one point he created a sort of dogma for each race and I don't remember if it ended up being strictly how we adhered to it, but the first race at the end of the academy when he wins, part of the point of it is that they're overwhelmed by the physicality of the real cars as opposed to the video game, and they're getting thrown around by the weight of it, and so he said, “We're going to use a lot of that engine footage.” And so in that race, we introduced those mechanical shots. For several other races, for a variety of reasons, we had certain rules of what kind of shots. For one race, we used these micro drones where the cameras are whipping around the cars in this really dynamic way. So each race has sort of a distinct flavor for a specific reason. And then the finale at Le Mans, everything mixed together, and I thought that was really cool.

PARKER: I think there were 5 or 6 races and the first time we presented to Neill, they were still the early versions of the cut. Firstly they ran long, but also they all just sort of blended into one giant race. Sort of like a Phish concert, I imagine, all the songs sound alike. But Neill came in and gave specific rules. He’d say, “Red Bull, we're not going to use the drones.” So each race, we were disciplined to certain cameras we could use. And then the Le Mans race, which was sort of Austyn’s baby. That was the kit and caboodle, when we go back to Le Mans, you can use everything.

DAINES: It really set up the stakes of like, why we were showing that race. This is the point of this race. This is what we're trying to tell the audience and how we're trying to do it. Neill wrote an email to us all and just kind of like laid out the important beats and what we were trying to achieve with each race. I keep thinking about how awesome that was to have and use as a guide when we were building those sequences.

Can any of you talk about how you deal with handheld as an editor, kind of dealing with the camera motion itself almost being performance or how you get in and out of a handheld shot to something that's more, tripod or dolly driven?

Can any of you talk about how you deal with handheld as an editor, kind of dealing with the camera motion itself almost being performance or how you get in and out of a handheld shot to something that's more, tripod or dolly driven?

PARKER: I have no philosophy about it. I just picked the shots that seem cool and then look at it and see if it feels like we're missing anything. I think the overarching rule for this movie was to try to make it from Archie — our protagonist's — point-of-view as much as possible, especially the handheld stuff where we're tight with him. I think the only rule is basically trying to find the next shot after the shot where you're tight with Archie, the next shot either being literally a point-of-view shot of what he's looking at or what he's encountering or something that can feel like it. And that was another thing that Neil continuously gave us the note: it needs to be more from Archie's point of view, more point of view and more point of view.

The way that Neill shot it — and a lot of his movies are very kinetic, almost looks like war photography, and so it's just kind of innately in the footage. It's not like we're trying to find the cool handheld stuff because there's just so much of it.

That's my feeling from District Nine, was that kind of wartime photography feel to it that it feels authentic to a documentary.

FREIDENBERG: We kind of stole a thing from District Nine also where they go to camera angles often it's like unclear. Are we watching the movie or the TV show within the movie? And we kind of did that a lot, especially in the racing sequences where we would take a shot that felt appropriate and put TV graphics and an announcer over it. So it's like all of a sudden you're aware that this is a televised event and you're changing perspective and then you're sucked back into being really intimate with Archie again.

DAINES: He's really known for making things look very verité. He's just so good at that and mixing visual effects in that as well. I remember him in Victor, our visual effects supervisor, revising so many shots, especially for car crashes because Neil was so particular about it looking real and not making it look too perfect or too Hollywood-ized.

FREIDENBERG: There is definitely some kind of cool irony. I think we're almost all of his other work is science fiction, visual effects heavy, and then this is a movie where he wanted it to feel as though there are no visual effects.

I love some sound design around the hero character Jann, when he has an idea — when he's on the racetrack and he sees a new line that he could take — there's sound design which kind of lets you know he's thinking, Can you talk about that? And did the sound design change the visual cutting?

PARKER: It's there to elevate. But with all these Gamervision scenes the ultimate goal is to transpose the audience into Jann’s head or make us feel like we're sitting next to him. And these were mandates from Neill from the beginning that he loves hearing these radios, but it's hard to hear and it's hard to actually articulate exactly what we're hearing. And he wanted that experience. There's certain points where we drop out sound just to hear Jann’s breathing and really be inside Jann’s head. Obviously, to that note, the graphics, the way when he was playing the video game, what it looked like to him. And now we're seeing the video game, but we're being transposed into the race car with him. And it's all about sort of living what Jann’s living and what this character is living. And I think that was Neill’s vision was and it was our job to translate into the film, and so that was definitely a conscious decision. Obviously, an editor's job is to execute and get Neill’s vision to the screen, and then we would obviously embellish it and try to enhance that.

Eric had a scene — he's kind of the first guy to really drop the engine and all sounds and hear the breathing. Neill reacted well to that and he was like, “Let's try that in a few other areas.” Something I'm really proud of in the film is it does feel like you're in the race car a few times.

FREIDENBERG: Gamervision was the idea that when he's in a real car he's using the lessons he learned from the video game. So we took the way that these lines are laid out when you play the game and then use the actual Gran Turismo sound effects whenever we could. That turn when he starts racking up points going into the end of Le Mans I still get goosebumps. It’s so satisfying when he hits those markers and it's like bling, bling bling. It helps a lot, and it's also really cool for the gamer hardcore audience out there.

PARKER: Also, we used it during the police chase because that was unscripted and that one really does the job well of explaining how he's using this skill to evade the cops and then later, obviously to do well at Le Mans.

Tell me a little bit about the Tokyo montage. Was that something that was maybe longer scenes and it got shortened down? Was it scripted like that when he goes to Tokyo with his girlfriend?

Tell me a little bit about the Tokyo montage. Was that something that was maybe longer scenes and it got shortened down? Was it scripted like that when he goes to Tokyo with his girlfriend?

DAINES: Originally that was scripted as scenes. They shot all this great B-roll of them walking around Tokyo, which is really cool. There was a scene that we took out where they did karaoke. It was a cute scene, but it just took a really long time. There was also them at the sushi restaurant, which originally was a much longer scene with some dialogue between the two of them, but at that point in the story, I think we really wanted to feel like that was a fun date night, but also just start moving things along and find out what happens next with Jann on the track, so we ended up making a montage out of that.

I will say something really cool about the sushi restaurant is the sushi chef? It's a cameo by Kaz [Kazunori Yamauchi] the guy who actually designed Gran Turismo.

FREIDENBERG: It's very similar to your line of questioning about the GT Academy montage. Each beat or scene was very long and it got conflated into this awesome feeling montage by the end. Also just a tip of the hat to Austyn — I remember looking at a cut — they’re in the sushi bar and he gives them this sushi and in the first cut, it just kind of gets glazed over and as a sushi head, they're in Tokyo and they say, “It's so good. Give me more.” But we never really see the sushi. And Austyn went in and found a close up of the sushi being presented.

DAINES: Eric, that was for you, man. I think you gave me that note when I showed you that cut. “Where's the sushi?”

PARKER: Eric gave me that note too, and I wasn't working on it.

DAINES: I’m glad we’re talking about it now because that is a make or break shot in the whole movie. Neill did say that was one of the top sushi restaurants in all of Tokyo that they shot at.

In the Nurburgring race, I love that you just start right on lap six. Was it scripted like that? Or did you have laps one through five and you decided, “Yeah, these all have to go.”FREIDENBERG: It was not scripted in my recollection, and I think it was just so cool to come in hot like that.

DAINES: The fantastic Red Bull race that Colby put together, was really about Jann getting into the car, the whole setup, getting rolled out, doing the warm up lap. By this time in the movie, the audience has already experienced that, so it was time to progress and move away from that.

Near the end of the movie is a sequence that I called “the dark night of the soul sequence.” Something bad happens and things get a little emotional for a bit. Tell me about determining how long you need to be in that segment for it to be effective, for you to know the weight of it, the emotional weight of it and how long before you say, “We got to get onto the next thing.” He can't be sad about this for the rest of the movie. We got to move on.

PARKER: First you have to give credit to Neill and the actors because he's directing them and they're giving incredible performances throughout. It's a shame what is on the editing floor because there's tons of great footage and all the actors really went for it. But as editors, we're searching for the most impactful performances to provide an audience with an elevated experience. So the performances speak to you and then you see what is relatable to you or what you find an audience can relate to and what is believable. I've cut a lot of these scenes within different movies, especially doing a lot of movies based on a true story. I always kind of lean on personal experiences as well. I've cried a lot in my life, so I just fall back on personal experience and what is the most believable and authentic.

FREIDENBERG: To me it was written pretty close. Those scenes were actually pretty close. And like they had reckoned with this in the writing, “Okay, we know this has to happen. The hero must be challenged.” It really happened. So we cut each of the beats on its own. When the bad thing actually happens — right afterwards in that that mayhem — Austyn cut that scene and it's one of the only bits of the movie where there's no dialogue at all for a couple minutes maybe and I think that was very effective. Like it works really well and you stop down the pace of the storytelling for a couple of minutes to let it wash over you and it’s also, I think really important to do it right. And I think it worked really well.

DAINES: The first time reading the script when that happened, I was blown away. I thought, “There's no way this happened in real life.”

The parents are at the beginning of the movie and they're pretty strongly at the end of the movie, but during the middle of the movie they're kind of gone. Were they there in the script? Did you feel like you needed to keep them alive in some way? For example, in that “Dark Night of the Soul,” the parents are in that section and it's pretty powerful that they're there.

DAINES: There was a scene that we cut out after the Tokyo sequence. He went back home and met his parents for dinner and kind of explained that he got a contract with Nissan and we cut it and cut the scene a few times and it just ended up slowing down the movie when we needed to progress.

You already know he’s got the contract, right?DAINES: You already know he's got the contract. You know that his dad isn't very supportive of him. And so to just move the story along, that was just one of the things that didn't end up in the final film. And I think it was a good move. The story moves along great. That scene that you're just talking about when he's talking to his mom on the iPhone, that was a moment where we could understand their side of things. The parents were great. Jann’s dad specifically was fantastic. Colby cut the most emotional scene with Jann’s dad, with Djimon Honsou and Archie Madekwe in the trailer before Le Mans.

PARKER: That's where my daddy issues came in handy.

There's something to that, right? Let me just talk about that. It doesn’t have to be daddy issues. I was just listening to James Cameron talking about the lived life of a filmmaker and how important that is. You can know how to run an Avid or Premiere. You can know how to run a RED camera or an Arri, but what really makes you a filmmaker is that you have lived a life, know people, find people interesting. Talk to me a little bit about that. The value of your life experiences when you get into the editing room.

PARKER: Pete Berg literally had said that sentence to me: “I like you, Colby, because you're not some nerd. It looks like you've done LSD a few times in your life.” You kind of have to get out of the room and live life and be able to relate to these different scenarios. We're storytellers, so we have to be able to inject parts of our lives and our experiences into our editing, which we all do.

We definitely screened the movie every Friday more than I've ever done in any other film, But we would screen it and we would give each other the notes and then attack those notes and address them. We wouldn't just say, “Do this.” We articulate why and give everything a purpose story-wise. “This is going to advance the story.” “This is for character.” Both Austyn and Eric I consider very methodical editors, fantastic editors, and they would actually put me in check a lot of times: “This is what we need for the story.” “We need more character here.”

I don't think this photo qualifies as "see/say" for "We played sports in our youth..."

FREIDENBERG: I think it's really true in everything in life, but especially in making something creative, making art. I always say, no matter what I'm doing, I have to fall in love with it. You know, like years ago, I cut a Lady Gaga documentary and for a couple months I was huge into Lady Gaga and her story and her hero's journey moved me, and it still does. And you just have to really do that with all these characters. All three of us played sports in our youth. It was very easy for me to relate to Archie and his journey. So it's kind of like my editing journey and learning a bunch of technical skill, but you also have to trust your instincts, and it wasn't hard for me to relate to that. I agree with everything that Austyn said about the father-son relationship, which is sort of the core of it. We had versions of the cut where in the first act Dad was kind of just a dick. Everything he said was, “You'll never amount to anything if you keep chasing your crazy dreams.” And then we sort of pulled it back and Neill gave that note several times where you felt the love of the dad and you understood that he was doing this not just because he's a curmudgeon, which I think, those little nuances are the difference between this feeling like a good movie and an after school special. There's a couple of beats along the way — there's a scene where they're sitting at the dinner table, I think Austyn cut that scene and it feels really important in the end. That's the scene that sets up all of the emotional payoff. There's also exposition that’s helping us understand our character and the journey. I think it's very well written and acted and directed and it all plays out really, really beautifully. And then when they they hug and cry at the end, it feels really impactful. That dinner table conversation was really subtle. We changed the dialog here and there and took a line out or a line in, but a lot of nuance to the reaction on the dad's face that I thought we ended up sort of making him into a real human being in a way that I really liked.

DAINES: Djimon is such a good actor. It really makes anything that we do look good. He's very subtle. That scene originally there was more exposition, more kind of the same beats that we've learned in a few other scenes with him in the first act, and so it was really finding what parts do we need to learn here without Jann’s dad coming across like a total asshole.

PARKER: I’d ask Austyn what made him put in this Michael Mann track, since I’ve been asked about it numerous times.

DAINES: Well, that is Moby. Not Michael Mann, but it is famous in the 1994 movie Heat. I did read an IMDb comment that did not appreciate us using that track.

PARKER: Tarantino can do it, but no one else can: take existing songs from existing soundtracks.

DAINES: Neill and I've been working together for a really long time and a lot of times he'll send me tracks and I'll send him tracks. For the end of Le Mans, I know he wanted something that was needle drop. One weekend he just said, “Dude, we got to find the right piece of music.” He's also very big into electronic music, so I just started listening to Spotify. I do this a lot when I'm putting scenes together: I listen to Spotify, find a track that I really like, or that is kind of the right vibe, and then create a radio station off of that, and so I put a put a playlist together and I sent Neill the playlist. He said, “Oh, this Moby track is really interesting. Let's try that.” And then we put it on to picture and it kind of stuck.

PARKER: And then they got the price and it went away and then it came back.

.jpg)

DAINES: It was way too expensive. We couldn't afford it.

PARKER: Actually, the head of Sony, Tom Rothman, said, “Where's that track?” Because we had taken it out for budgetary reasons. We said, “It was too expensive.” He's said, “Put it back in.” So we did. He said, “That was the emotional punch. We need that.”

FREIDENBERG: He said, “You’ll be surprised to hear me say this because people know me as the cheapest guy in town, but I think in this case it's worth the money.” “You changed the music, right? I put it to you this way. When that scene used to play, I felt something. When we play it without that music, I don't feel it as much anymore.”

A good note. A good note.PARKER: I think a lot of people are curious about that.

FREIDENBERG: Also, something that Colby always says is “no umbrellas at the brainstorm”

“No umbrellas at the Brainstorm.” I like that.DAINES: Colby, Do you remember towards the end we were trying to figure out, all the songs we could get in and we had these spreadsheets. We were putting together our top favorites. Neill was at The Coffee Bean and we walked over there to him was said, “This is the priority list. This is what I think we need to fight for.”

PARKER: Yeah, because we actually did censor ourselves a bit with those songs. But he said, “No! Put these songs back in” and we walked back and gave ourselves a silent high five or said, “Yes, he's going to fight for him.”

Thank you all for being on Art of the Cut and having such a great conversation about your movie.PARKER: Thank you so much, Steve, and thanks for flying the editorial flag and cinematic flag. We all appreciate you.

DAINES: Steve, I'm a huge fan of your podcast and almost every single day on my way to the studio, I was listening to your show and it kind of provided some sort of motivation to get through the day. And it was really inspirational and I really appreciate everything that you do. Thank you.

I want to ask Austyn one last question. What did you think of the switch from Premiere to Avid for this one?

DAINES: I've worked in Avid periodically throughout my career, but never this much. I was a firm believer in Premiere beforehand, but then had help from a friend editor to get me prepared when this came about. The first couple of weeks it took me a little bit to transition, but I would say the big thing for me is I just had to like retrain my brain on how to think. They are different. I feel like Premiere is: you just grab and throw things on a timeline and it's very user friendly in that way. And it's also very elastic and you can just do whatever. And I feel like with Avid, it's more premeditated — your thought process. So once I kind of just trained my brain to think differently, it was pretty smooth. I love my experience with Avid. Obviously, there's like little things that I miss about Premiere, but I would say the same thing about Avid and I think both are perfectly good platforms, but moving forward, if I get an opportunity to cut another one, I would probably stick with Avid.

PARKER: That wasn’t the answer I was expecting. I thought you were gonna say, “If I had my druthers. I'll do the film on Premiere.”

Gentlemen, thank you so much. Have a great day. I really appreciate it. And we'll talk to you on the next one.PARKER: Thanks, Steve.

DAINES: Thank you so much.

FREIDENBERG: Thank you.