Today we’re talking with Nena Erb, ACE. Nena has won two Primetime Emmys for her work on Project Greenlight and Insecure. She also has three ACE Eddie nominations - two for Insecure, and one for Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.

Her other work includes editing Justin Bieber’s Believe, the TV series Little America, and the feature film Little Owl, which also just released.

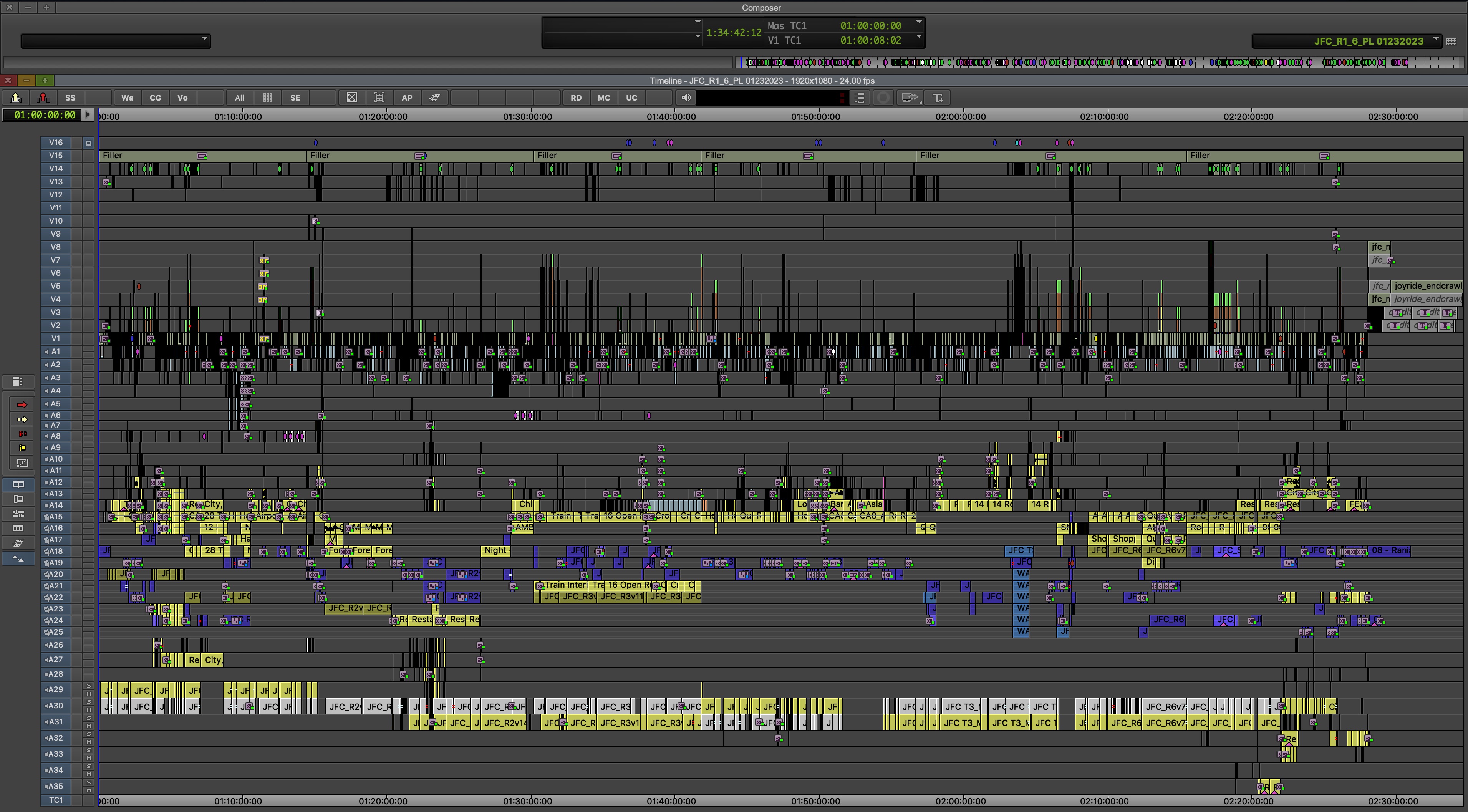

Art of the Cut: Joy Ride

This is a first-time director for you and a first-time director period, right?ERB: I worked with a lot of first-time directors. They had quite a few come through Insecure, but this is definitely [Adele Lim's] first feature

How much hand-holding do you have to do with a first time director? Does it change the way that you make suggestions?ERB: It definitely does. Because they're not used to conversations in the cutting room, I have to be a little gentler. If something is not going to work, I'm not going to say, "No, I don't want to do it." I would say, "Ok, let's try it, but I'm a little concerned that this is coming across this way or that way."

Adele is great. She fully admits that this is her first turn at it, and she tells me that she will ask for things and to let her know if they are impossible. She was very chill about the whole process.

There was a trust that was built early on. We would screen some cuts, do some notes, and then she would leave me to do my work. There was a lot of trust from Adele.

What was the collaboration method between the two of you when you work through story issues or editing after the director's cut?ERB: down. Even then, there were still so many other jokes that were funny. It was a lot of playing around to make sure that she had what she wanted for her director's cut.

Afterward, the cut we presented was still 2:20.

10 minutes is a good amount of time to cut. You're getting there.ERB: When the producers came in, they had to cut the runtime and make sure it is the funniest it can be.

The producers would say, "Alright, I don't think that joke is funny. Let's see what else we have." I would play all the different improv jokes for them. Then, the producers would shop for a take that they liked – the one that made them all laugh.

If a joke didn't work, it was gone. That's how we got it down to 1:45. We had a lot of exploration trying to amp up the 'funny.'

You've done a lot of comedy. What is that process like – getting through all the alternative takes, the improvisations, and the ad-libs?ERB: There could be easily twenty versions of this movie, if not more. Fortunately, ScriptSync made the whole process so much easier.

They knew when they wanted the alternative jokes to come in, so it was always in their coverage. Those variations tend to be the longer takes. The cast would say the scripted line, and once they [Adele] were happy with it, they would try out different jokes. They would riff. It would be all kinds of amazing, hilarious, sometimes not appropriate jokes, but they were really funny.

I have used ScriptSync before, but some editors expressed difficulty using it for ad-libs. How did you manage ScriptSync with those?ERB: I luckily have a very patient assistant editor. I watch everything anyways. As soon as she is done with the group, she would tell me, "This bin is ready for you." She would have marked down where the ad-libs are. If it is quick for her to transcribe it, she would do it right in the ScriptSync and then link it together. Sometimes, the ad-libs are complicated. I've told her to just write 'ad lib' and add a couple keywords to remember what it is about. Later on, when we have time, she can go back and fill it out.

That was our process because we didn't have a lot of time to get the editor's cut together. It was four days, which I was shocked. I thought, 'That's what I get for an hour episode.' This thing is 2:30 long, and I have four days. 'Okay, great.'

That is a short schedule. What did you do to notate or remember great takes? Not only do you have to remember those for yourself but for the director.ERB: I watch everything then I put my favorite one down on the timeline. Oftentimes, if it's really hysterical, I would make a note locator and rank it. 'This was a five – made me laugh really loud. This was a three.' Sometimes, I'll say 'decent,' which means it didn't even make a number. The jokes I loved went into the KEM reel - that's what I used to cut off of.

It is really helpful because four months later when you're doing notes, and the producers want to know if they laughed at a joke four months ago, you can tell them, "Yes, I named it a five. You guys thought it was six."

I realized I had to do that once I got into feature editing because the schedules were so much longer. You don't have other episodes to jump to and then come back with fresh eyes. You're just in one thing for a really long time. It's easy for something to feel stale very quickly.

Do you have any tips or ideas on being able to remain objective about a scene you've seen a thousand times?

ERB: I can disconnect my emotions very easily. When I'm working on something, I would step back, look at it, and ask myself, "Okay, if I don't know anything about this, is it still funny? Is it still making me sad? What about this is making me sad? How? What can I do to make it more sad?"

For instance, we tried a couple different versions of the mom video in the film. Of course, Ashley Park is phenomenal, and you want to be on the star of the film and see her reaction to receiving this mom video. However, we realized that is not as emotional as we thought it would be.

I want to be on the mom more because I want the audience to feel like this could be their mom giving this message. So, anyone who's lost a parent could identify with that. Anyone who has been adopted probably has thought about finding their parents could potentially feel a connection there.

When it starts to get too earnest as we stay on the mom, you go to Ashley for a little reaction or a chuckle. That ended up working really well.

There's a facial expression that the mom made at the end of the video that expressed so much sorrow. At first, I thought, 'I can't show that. That's too much.' Then, in the end, I thought again, 'I got to show that.' That's what ended up getting everybody.

I cried. You had me. You point out that a take can be too much.ERB: The film was so long during the dailies. By then, I was thinking, 'For pacing, I shouldn't be on the shot any longer,' so I didn't.

After we have chiseled away, found the film, and found the arc for Audrey, I feel like we did a better job with making sure people are with her.

There was exploration for all the characters. I would say Deadeye's evolution really went full circle. When I got the script, I remember reading it, and realizing Deadeye was going to be an interesting character.

This is probably the first Asian non-binary character in a movie, so I needed to be really careful with this character. It is easy to make them the butt of the joke or so out there that the audience thinks, 'Oh, that person is really weird.' I didn't want to do that. I really wanted to make sure that Deadeye came across relatable.

In my editor's cut, I believe, they came across that way. Through the process of exploration – because you always want to make sure you're using the funniest stuff – there were other performances where Deadeye was a little more aggressive. Some of them were really funny, but once you put it all together, collectively, Deadeye's character became less likable just because they were screaming a lot, which appeared angry. So, while that performance might have been funny on set, once it is in the film, it just didn't translate.

In previews, we got that comment that people weren't really latching onto Deadeye much. We decided to go back to the editor's cut and make minor adjustments from that.

I think because I chose to make them socially awkward, wanting to belong, and be friends with this group of women, that made it a little easier for people to take.

So many people have asked me, "I'm in unscripted. How do I get to scripted?" Not that that needs to be the progression, but so many people want to make that jump. How was that possible for you?ERB: It was possible because I didn't take no for an answer. I've been very lucky.

You've done so many of the top unscripted projects.ERB: Once you do it, you think to yourself, 'How many more seasons of Top Chef can I do?' I wanted something different, and I kept at it – asking for people's recommendations if they hear of any new projects. Then, I noticed that there was a period of time when they had scripted shows that were parodies of reality shows.

There was Unreal, a parody of The Bachelors and the whole franchise. There was Real Husbands of Hollywood – which I did – that was a total parody of The Real Housewives franchise – which I also did.

So, I thought, 'Alright, I have an in here.' I researched all the producers and figured out that I know people who know them. I called my friend who I met while working on Curb Your Enthusiasm when I was called in to do some assistant work. She said, "Tell this guy I know you, and he'll at least bring you in for a meeting," and that's all I wanted. 'Just get me in there for a meeting, and if I can't get the job, then that's on me.'

I went in, and strangely enough, they didn't care that I worked on the Orange County Housewives series. They were more interested because I worked on a concert movie. That season had a lot of performances, I think they wanted someone who knew how to deal with cutting that – a lot of cameras, a lot of music, and dance. It was pretty funny because I expected questions about the Real Housewives show, but I did not get a single one.

ERB: That is exactly it. In the beginning, I didn't make much progress in this transition because I was trying to come up with ways to hide what I learned in the unscripted. Then, I realized, 'You know what? I've learned a lot. This is a great boot camp, so I need to figure out how to reframe it.'

If it was a comedy, I would always ask them, "Do you plan on doing improv?" If they say yes, I would reply, "Great, because doing reality, there's a lot of material that we have to wade through and make it cohesive and coherent. I'm used to dealing with a lot of material, and I have a way of organizing it. I have a way to retrieve it in the notes process."

I'm also used to doing my own music and temp VFX because you don't have a big team when you're on a reality show. You are sharing your assistant with four other editors. You have to be self-sufficient, and I think that really sold it, at least for the team I was on. The Real Husbands of Hollywood team said, "This thing is fully scripted. There's not going to be a lot of improv, but we like that you know how to cut music, and we like that you are not afraid of doing temp VFX."

I talked to Chad Galster who cut Yellowstone. He said he got the job because, supposedly, Taylor Sheridan said, "I want an unscripted editor." He asked for the best unscripted editor from a buddy of his who happened to know Chad. I think people recognize the skillset – being able to construct something, find a story, and deal with a lot of footage. Working with ad-libs is one of those things I'm curious about in your editing process. Of course, you have to find the best joke, but because these things are not consecutively, you can't assume everything else will flow with that joke. You're trying to pull funny lines from all the different places. How does that affect your editing?ERB: It definitely was challenging. In every single scene, there are different jokes and different ad-libs. You would think that it'd be as simple as "Okay, here's the scene, and I'm going to take this joke out and pluck the other one in."

It doesn't work that way because people are in a different position. Maybe, this joke came a little later when you want to move it up, but you have to remember "Where did I hear that?"

Little pieces of words – and, or, that, but, the, and then – help transition into the joke or get us out of the joke.

Also, split screens have become my best friend. You do it so that continuity makes sense.

Do you use split screens in two shots or over the shoulder? A little of everything?ERB: A little of everything. In the opening scene at the park, we had Audrey's parents come up to the Asian parents. They both had great improv jokes, and we were playing around with them in the editing room. Then, we realized that we have to shorten the interaction because we want to move this along. We couldn't stay with them too long.

Through the process of cutting and losing certain things, the Asian parents weren't turning around at the right time. When they hear Audrey's parents, they were standing in a certain direction because they were in another part of the scene. I had to figure out how to make them turn around and say hi to make this scene work.

I found a take for Jenny, Audrey's mom, where she looked over her shoulder. I thought, "Okay, this could work because I just need one of them to turn around." That's what I did – split screen that and slid the line of "Hey." Jenny turns around, and I immediately cut to the Asian parents. There is a lot of that throughout the entire film.

Once you're handheld, you're in really difficult territory for a split screen.

ERB: Sometimes you can still make it work. You can stabilize a shot, shockingly. I actually learned on Insecure how to add a camera movement – a handheld feel. I would think, 'Let's make these shots static, and do my split screens. Then, I'll put the camera movement on it.'

What's your process or approach when you're in dailies? What do you do when you get new footage and you've got an empty timeline?ERB: I read the script of the scene a couple times and try to figure out what one character wants from another. By the time I'm watching dailies, the lines are baked in my head, so I don't have to look down at the script while listening to the lines. After that I throw it together very quickly so the bones are there.

As I'm putting it together, then, I'm always thinking, 'Oh, wouldn't that be interesting if we cut to that other take?' I will copy the sequence and do an alternative cut. From that, I'll come up with different ways to get into a scene and get out of a scene.

Someone was talking about cutting something from the middle out. I don't remember where, but it made me realize I want to try that. That's interesting, so I found a line that we can build the whole thing around. It got a little messy, but I think I want to try that again because it was such an interesting exercise.

It forced my brain to think in a whole different way.

ERB: I have my bins open when I'm watching it, but I close them and use the script once I'm ready to cut. When I'm watching dailies, I'm always putting selects I like on the timeline. I'll work off of that select reel. It will be a massive reel of things I liked. I usually try to build off of that.

Then, I'll go back and really use ScriptSync to audition all the tapes and make sure that what I have in there is the best one.

That is what you're saying about the bones at the scene. If you want to be on a closeup at a certain point, you just have to look at all the closeups.ERB: Yeah, but I also look at the other stuff because sometimes you have a great performance – it's on the wrong shot, but sometimes it fits. You just take those words and put them right in their mouth. Sometimes, I'm lucky, and it works great.

You've got an ensemble cast and the juggling of characters. Talk a little bit about that need not to always be on one character or not to lose a character in the midst of other characters.

ERB: That was a challenge because there are four of them.

My first edit leans towards whatever I felt was the funniest. Sometimes, that may not do all of them justice. It would just make one of the characters shine, so it's good for me to look at the cut and think, 'Okay, let's try and balance it out a little bit.

Audrey – she is the straight woman. It was her story, and it was all through her lens. If there was an improv where she shined, that was definitely staying in the cut.

It was a balancing act for sure.

Audrey couldn't speak Mandarin, but she could speak Gollum, right?ERB: That was so funny. I'm so glad it stayed in the film.

Talk a little bit about intercutting. There's a great series of intercuts at the hotel because all the characters go off their own separate ways. Normally, the four women are almost always together until the hotel. Their stories are intercut. To me, it got faster and faster as we got to – I will just call it – the climax.

ERB: Yeah. Definitely. That intercut actually each started as scenes. That whole montage was very long – five minutes. It definitely didn't work at five minutes, so we had to make sure to ask, 'What are we trying to tell with this story? What is the story of Kat and Todd? How do we quickly do we get to the basketball and the Theragun?'

For Deadeye, it was all about trying to do a dance-off. That was our comic relief. When things were getting a little too uncomfortable, you throw a little something funny. It was a lot of whittling things down and debating on what the funniest part is. 'Is it Lolo saying tongue and lips when she's trying to kiss Baron?'

There was one dance that we really cut down. I thought it was great, but we didn't need it. It was a moment when Deadeye is facing off Jiaying, and she had this double-middle-finger move – which she did the morning after at the coffee table.

Once we got the form, we knew they should be faster and faster because we don't want to linger on any one thing. It was a dirty montage. I tried my best to make it funny and not an uncomfortable thing for people to watch.

There's a lovely montage – I called it the "Love China Montage," where Audrey thinks, 'I love China.' Talk about giving the audience a moment to breathe or to let the story open up a little bit to have those little lovely moments.

ERB: Those moments are definitely important because I feel like the pacing of the film is fast and furious – there's a lot of things happening, a lot of music, and just a lot. Part of the reasons that drew me to the film is that it was supposed to show you what China is like and what Asia is like. Of course, it's been in the press already that we shot in Vancouver, so it was a challenge to make it look like they shot this film in China.

Our production designer did a phenomenal job. I use those moments to show what the countryside in China would look like and what the little rivers look like. It was just a moment to stop and look at the scenery to remind people that this is still a road trip movie – this is the scenery that we're walking through.

We're also making sure that we know that Audrey's slowly falling in love with the country ¬– one that she was shying away from before. It was important to put a lot of culture-specific jokes in there. For instance, the little boy driving a moped with all four of them on it because that happens a lot.

I've been to Vietnam and to China, and it definitely happens. There's an entire family including a newborn on moped – and groceries. When I was in Vietnam, I was talking to my interpreter about a crazy thing that I saw, which is a guy driving with two full-sized trees on each side of a moped. Then, he said, "Oh, I got my full-sized refrigerator delivered by a guy on a moped."ERB: It was very important for us to use that shot. There was never a question whether that shot was going to be in the cut, but I'm also used to doing my own music and temp VFX because you don't have a big team when you're on a reality show. You are sharing your assistant with four other editors. You have to be self-sufficient, and I think that really sold it, at least for the team I was on.

The Real Husbands of Hollywood team said, "This thing is fully scripted. There's not going to be a lot of improv, but we like that you know how to cut music, and we like that you are not afraid of doing temp VFX."

The movie is very funny throughout. I'm sure juggling different tones was a difficulty because you do have to have these emotional moments – you have an emotional payoff.

The movie is very funny throughout. I'm sure juggling different tones was a difficulty because you do have to have these emotional moments – you have an emotional payoff.

ERB: Definitely. We had to be very careful with that in the transition – the in and out of the emotional moments.

I think inherently there are certain scenes that are just supposed to be more emotional – and that's okay. The scene where Audrey is getting dressed in the morning before they go to the adoption agency is an example. That was a very sweet and emotional scene – her revealing to her best friend how difficult it was for growing up as an Asian child adopted by white parents.

After it gets a little too earnest, you want the grandma to come in and do a joke. It was about picking the right moments.

The other thing I noticed was giving the audience time to process certain things.There were mini montages or little moments where you're thinking for the audience, 'Okay, you just discovered this huge, important thing – or the character just learned something terrible.' You let the audience live with that for a second.

ERB: We definitely needed to do that. That goes hand in hand with smoothing out the change in tone.

I think we experimented with different ways to let the audience sit with it. At one point maybe we didn't let them sit with it that much, but it's just a lot of playing around and seeing how it felt. I hope we arrived at a good balance.

I think so, but where that's really tricky hinges on the runtime. You can feel that balance when the movie is 2:30 long. You think, 'The pacing is very lovely.' But then you get it down to 90 minutes, and now everything you did is out the window. How do you maintain those quiet moments in a 90-minute film?

ERB: It's about making sure the funny parts are fast, so you have a lot more room for the times when people can slow down and take in information.

It's so funny because someone once told me, "Comedy's very fast." I remember thinking, 'Is it really?' I hadn't realized it then, but it really is. I've tried it slower once just to see what that would feel like and it was terrible.

Comedy is also changed a little bit. I was watching Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, and they would sit on a two-shot forever because you got two great performers in a two-shot together. Why cut to the close, right?ERB: I tried to do that for one scene, but it didn't work. I was trying to not make it fast, but I realized, 'This is not funny at all. I should get out of the shot.'

I want to talk about two specific things. One, I really love the rhythm of the slap scene. Is it built to a climax? It just felt very rhythmic – I could almost hear music underneath it.ERB: Oh, that's great. That scene was not scripted to be that at all. The first two guys had a longer slapping game before the ladies came up. They also had a very long slapping game – when they would tie, they would both slap each other at the same time.

They tied twice, and then the third time was when Kat won. She smacked the crap out of Lolo – in between, they would throw little jibes at each other. It was funny, but it just was too long. We tried a lot of different ad-libs for that, but nothing felt right.

I asked, "What if they just beat the crap out of each other? Let's try that." They were worried. "We didn't shoot it that way. How are you going to do that?" I replied, "I don't know, but I'm going to try."

I'm glad it felt rhythmic because I wasn't sure that it came across that way.

I think most people – if you've seen that scene – you wouldn't believe that it wasn't shot for the way that you cut it. It just seemed natural to me. Then the other one – which is such an obvious question to ask – is the K-Pop music video. Just talk to me about the craziness of that. Did it go longer? Was it not crazy enough, and you made it crazier? Was it too crazy and you made it less crazy?ERB: My first cut for the K-pop video stayed until literally the last month when we were trying to lock for the final preview.

The shots were all green screen when they were not in the airplane hangar. We were using that with images from throughout the entire film to remind people of their journey. That was going to be the story of this whole K-pop number.

I think the choreographer did a phenomenal job, and I hope he's happy with the cut, but we did have to slow down a lot of it. I think the final cut was more beneficial towards story versus choreography.

You have had a little bit of experience with that with High School Musical.ERB: And Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Lots of performances.

One of the things that I thought of as an editor watching that was: Did you have all of that material the first time you cut that video together? Or were you and the director and anybody else asking, "You know what we need? We need an animated cat licking the screen."ERB: We had nothing. It was literally just green. For a split second, when I cut it together, I was thinking, 'Do I leave it green? I don't know. What would we put back there?'

The second assistant Melissa Kan – she's an After Effects genius. We found a lot of different textures that were in Getty Images, and then she tempted it all in and cleaned it up. That's what we screened with the first time.

We always knew that we wanted something that would remind everybody of their journey in the green-screened area, but we didn't know what. That definitely did not come until later, which is why I had to slow down a lot of the edits so that we could be on one shot long enough to see the animation – of the cats in the inner tubes spinning or the Theragun and the basketball.

The Licky Cat came in at the very last minute. I think we were still approving versions of that up in Canada when we were trying to do DI.

Another thing I was curious about, editorially, was trying to manage the epilogue. You come to a conclusion of the movie. Then, you now need to wrap things up, but you can't that go on forever. I felt it was a very good amount for me. I thought, 'I'll hang out for this,' but that could just go on forever. You'd feel like you have five endings. How did that epilogue evolve?ERB: I had to be brief with each little pod of stories – each little visit. Looking at the statue and commenting on the food – everything was all longer. Their hellos and reunions were much longer too, but we cut them down. Let's go to the dinner because that's really where you get the wrap-up. Of course, there are tons of ad-libs and jokes there too. We had a process of deciding what information we want out of here and how we want to mix the jokes and information.

Again, it was a lot of looking at it, saying, "Yeah, it's not working," and chopping away. Anything people missed, we would go back in.

You mentioned the VFX – at least temp VFX – was done by one of your assistants. Let's talk about assistants – finding them, knowing what to do with them, knowing in an interview, 'What's valuable for me to get from an assistant?' What are those things for you? What strikes you to pick an assistant? Or when they're working for you, what makes you think, "This person is fantastic. I cannot let them out of my sight?"ERB: I'm working with Gioia Caruso right now, and she is fantastic. I had actually met her years ago.

Troy Takaki had an ACE get-together, so a bunch of us editors were at this wine bar. I met her there. She would just pop up every now and then at different events – different ACE events.

I had a great assistant for many years – Lynarion Hubbard. She's cutting now and doing amazing. Trying to find someone to replace her was really tough because she did it all. She did everything.

That was a part of the conversation: how are you with After Effects? First, I want to make sure that they're interested in After Effects because some people just aren't. Some people have the sound design as their thing. I always find out what they're interested in.

As I'm talking to them, I ask them to walk me through one of their days. Depending on what they say, it is very telling whether we are going to get along or not.

How is that telling? What would be the giveaways?ERB: I'd want the assistant that would say, "If the dailies are there by 8 AM, I will be there 8 AM. I'll get started right away. So you have something to cut by nine or 10." This person understands that their job is to make the editor's life easier, not the other way around.

Also, I need someone that has the ability to anticipate. The best example of that would be where I'm at right now. Gioia and I screen things in a screening room, not the edit bay. I have a very crazy mouse. It's a vertical thing that's on a wedge. There's a trackball – very specific. It's that way because I had carpal tunnel.

Gioia doesn't know any of that, but because we're screening at a different place, she is thinking we should be prepared if they want to do notes on the fly. So, she grabbed my mouse, put it in the screening room, and set it up. I didn't even have to think about it because if it was up to me, I would've forgotten it and had to ask if she could go get it. She just knew to do that beforehand. I didn't tell her.

Someone like that is worth their weight in gold.

Do you want somebody that wants to be an editor or somebody that doesn't want to be an editor? What's your take on that?ERB: I prefer someone that wants to be an editor because I do like to bounce my cuts off of them and see if this is landing or not working. Is it emotional? Is it funny? Is this character more likable, less likable?

I feel like the assistants that do want to cut are eager for that kind of interaction because they can learn as well. I really value their opinion because they've seen the dailies and know what I have to work with. Sometimes, they'll say, "Remember there's that one other take where they did this?" It's good to have your assistant as more your partner as opposed to just as an assistant.

Where do you stand on – I've had this poll – the poll: should an assistant tell you that they want a cut? "Oh, hey, can I cut this scene?" Or is that something that you need to say? "Would you like to cut this scene?"ERB: I don't have any rules for that. I've had assistants tell me straight off the bat that they want to cut. Great. Awesome, because I want you to cut too.

I always tell them, "When you're doing dailies if you're like in love with a scene and you want to cut it, go ahead and cut it." If it's the first time I'm working with them, I will tell them that I'm still going to cut that scene too because until I know where you're at with your editing skills, I can't not cut it. I have to make sure that I have what I need to present my editor's cut. They usually understand.

If it's great, and they're really proud of it, then I'll put it in the cut. I will tell them if the higher-ups are happy with it. If the higher-ups are not happy with it, I say nothing. I just take the hits.

Sometimes, they'll sit in and observe the notes sessions. Hopefully, that's something that they'll also pass down to their assistants. They can cut alongside me. It would be a nice challenge though because if they can do all their dailies and all their work and still cut a handful of scenes every day, they're going to be fine when they're out on their own.

Absolutely. Thank you so much for joining me. It was really interesting talking about this movie and all the challenges that you had– basically losing an hour. Holy cow. What a huge job that is in itself. Congratulations.ERB: Thank you so much for having me. I definitely love your podcast, and I've learned so much from that. So it's been an honor. Thank you.