Today we’re talking with Langdon Page, one of the two editors on the Oscar and BAFTA-winning documentary, Navalny. For which the editors won a British Film Editors award and were nominated for an ACE Eddie.

Langdon’s credits include documentaries including Detainee 1, The Cost of Silence, and Maplethorpe: Look at the Pictures. He’s also edited the feature film Mary.

Navalny was co-edited with Maya Hawke, who was unable to join the discussion.

OSCAR and BAFTA Winning Documentary Navalny

Thank you so much for joining me.Thanks Steve for having me on. First of all, my editing partner Maya Daisy Hawke sends her regards. She couldn't be with us today, but she's certainly with us in spirit.

My first question for documentary editors always is why start the film the way you started it? It starts with this interview where he’s asked the question of, “What do you want to say if you die?” Why start the film that way?In fact, Maya was responsible for cracking the beginning in large part. With documentaries, as you and all the listeners know, beginnings are often the hardest parts. They get made and unmade and remade repeatedly. They're often the place where one starts and also the place where one ends in the editing process because the beginning seems to always be changing, depending on how the picture is coming together.

For a long time, we struggled. A large part of the body of the show was pretty clear, to a certain degree, but the beginning was always sort of evasive, elusive, as it often is. It was actually not until really late in the edit when we started incorporating more of the sit-down interview. We had that sort of sprinkled throughout all the way through the editing process.

Then, there was something that was missing in the cut. With Maya and director Daniel Roher — and especially producer Shane Boris, but also the rest of the producing team, Diane Becker — we just felt like we had this very riveting thing that was rocking and rolling and was very effective and we wanted to get it further.

There were a couple of things we couldn't crack, which we can come back to, but in the end, cracking those challenges was what opened up the clarity to start the film with that interview.

Let's go into those challenges. What were those things that needed to be cracked?In the case of Navalny’s story, we had a very compelling vérité thriller that Daniel Roher and the production team sort of fell into and were fortunate enough to have cameras rolling on in real time in Germany as Alexei Navalny was recovering from being poisoned with Novichok in Russia.

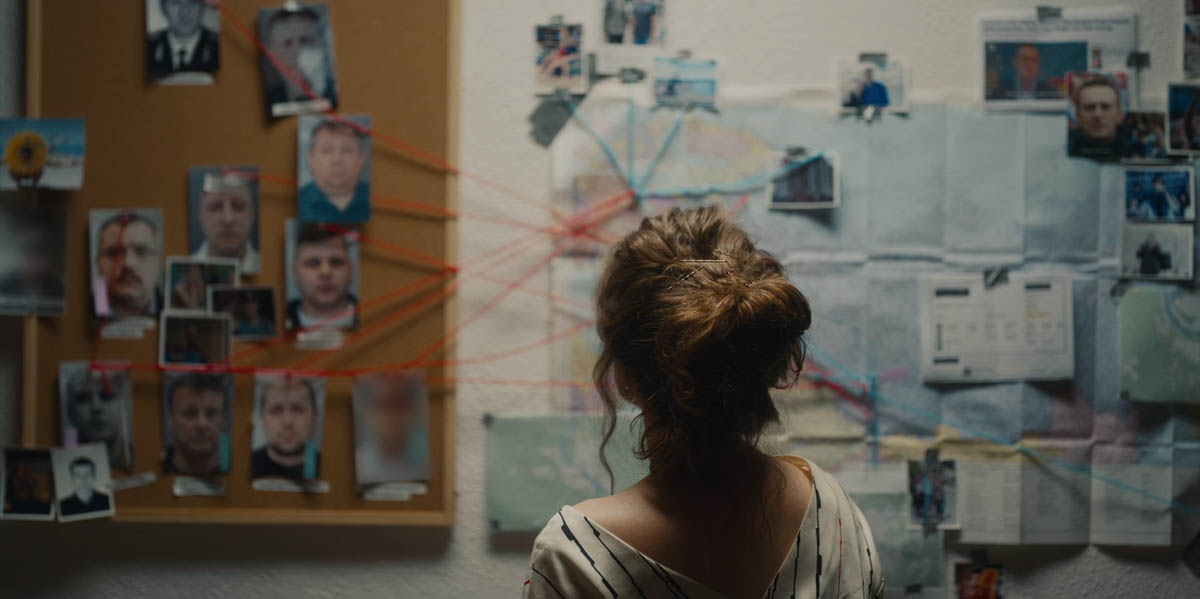

The body of the film was this thriller of his recovery, the investigation into who did the poisoning, in partnership with Christo Grozev from Bellingcat, who was a fascinating character in his own right, and Maria Pevchikh, who works with the Anti-Corruption Foundation, Navalny’s foundation that works day in and day out to reveal and bring to light corruption in Russia. It’s one of Russia's biggest problems in terms of undermining its democracy and it's one of the methods by which Navalny has for almost two decades been trying to bring down the corrupt regime in the Kremlin.

All of that stuff was happening in real time. That was largely the body of the film, all heading towards this somewhat incomprehensible ending, which was Alexei Navalny’s return to Russia and the very likely probability that he was going to be detained, if not worse, as soon as he set foot back in Russia as the leading dissident, highly critical of Putin's Russia and the whole corrupt regime.

There was this underlying tension in the film of why would this guy who's such a charismatic figure with such a loving family, with such noble ideals — which is to bring democracy back to Russia for the first time, many would argue — why would he risk it all by going back into the jaws of the tiger? Which, as those who watched the movie know, ultimately is what happens.

There are a lot of conundrums there, but in large part, most of the arc of the film was pretty self-evident. This wasn't a doc like so many where you start wondering about it's somebody's life from before, where they're gone and you think, “Okay, do we tell it in a linear fashion or do we play with chronology?”

Lots of films really need their structure to be constructed in the edit. This one, in large part, really wanted to have a very linear progression and chronology because it's just so fascinating and riveting as it unfolded.

The challenge was, how do we get under this guy's skin? He as a character is so charismatic and is such an effective wordsmith and communicator as a politician that Daniel was very conscious in the shooting and we were hyper-conscious in the edit of not being pawns to anybody's agenda.

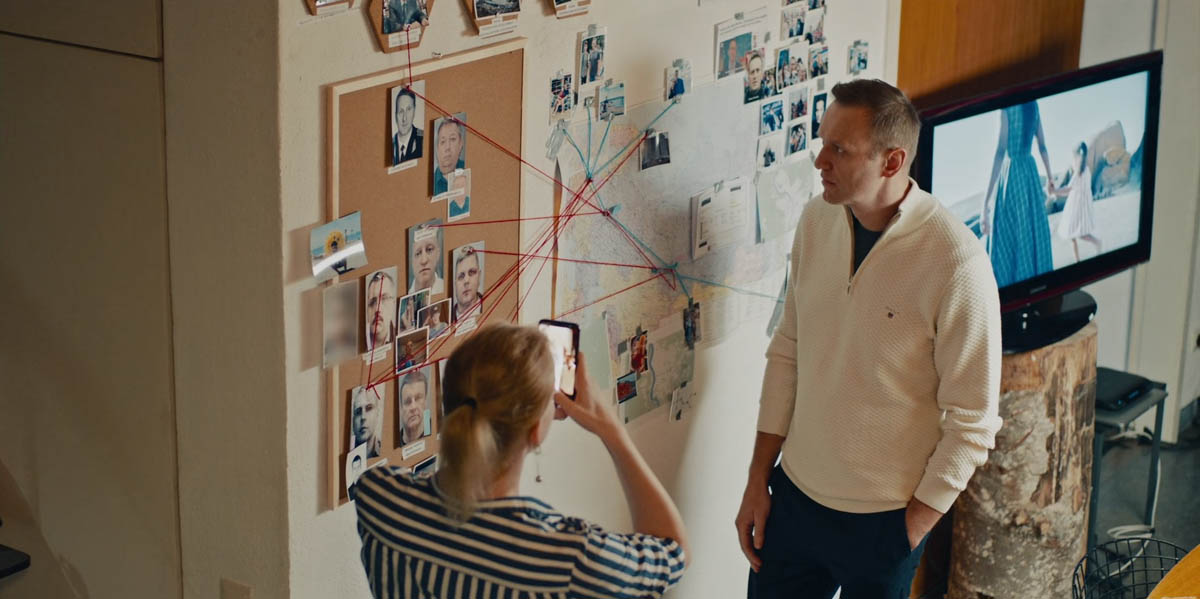

A photo from the color correction session.

Our role as documentary filmmakers was to hold this guy's feet to the fire and find out who he was because there are too many histories in geopolitics of foreigners getting involved in another nation’s quote-unquote “democracy resistance figures,” only to discover that, based on foreign support, those resistance figures come to power and end up being just as corrupt as the ones that were deposed or worse.

We didn’t want to fall into a situation of being either proxies for the CIA, which we knew we would be accused of by the Kremlin anyway, or unscrupulous people who just fell for this guy who supposedly represented democracy. There are a couple of very obvious historical things that Alexei Navalny has done and said that were massively problematic for us, specifically with regard to white nationalism or Russian nationalism and immigrants in Russia.

We knew that we wanted to deal with those aspects of his history in a way that didn't let him off the hook and try and understand where that was coming from and actually understand, is this guy who seems so charming and has this wonderful family and everything actually just a Russian nationalist? Is he a white supremacist? I mean, who is this guy?

We all followed the Navalny story in the news as the poisoning happened, but most of us aren't Russian history or current politics specialists. I didn't know. We had some obviously some deep advisors who are specialists in these things, but most of us are specialized in filmmaking.

We wanted to understand who this guy was and make sure we weren't selling or portraying a whitewashed version of a character who actually underneath had some horrible tendency.

That was the first challenge. How do we deal with what was commonly known as the Russian march — which we deal with in the film — a nationalist Russian nationalist march that happened in 2011 and 2012 that Alexei went to. He spoke at the march in a very inflammatory way, using the same rhetoric that he said at all of his rallies, which was we need to get together and drive out the corrupt current regime. Then we'll, once we have a healthy democracy installed, then we will have discussions about all these things. Visa regimes, immigrants, abortion, homosexual rights.

All of the issues that a healthy democracy has to deal with were secondary to getting rid of the corrupt authoritarian regime, which was squashing and clamping down on the rule of law and freedom of expression and the most basic elements of a democracy. That was his justification in going and dealing with this crowd of neo-Nazis basically. But how as filmmakers do we deal with that within the confines of a story where he basically is the hero of the story?

Langdon Page with Navalny's Oscar! It also won the BAFTA, and was nominated for an ACE Eddie.

That was our big challenge. We tried a lot of different ways of trying to understand it, trying to contextualize it. We had other people talking about it. We obviously reviewed all the archives. Alexei had in certain ways, at certain times, disavowed or recontextualized that moment to clarify that he’s not a neo-Nazi and that marching with these unsavory characters is a political necessity. In a healthy democracy, just like the ACLU has fought for neo-Nazi marches in this country, freedom of speech applies to everybody.

These are all very complicated things, but how do we deal with that in a way that doesn't derail the film, take over the film, and make it all about that? Ultimately, these are things that happened over a decade ago. After looking at different avenues to solve it, specifically getting “expert perspectives” from the outside or journalists — which are not ways that this film is constructed. There are no outside interviews, there are no sit-downs, other than the characters in the film — it became clear in sort of a bolt of lightning moment to me that what we needed to do was go back to the well and take advantage of the footage that we already had, which was almost 40 hours of sit-down interview that Daniel did with Alexei.

40 hours!He did it over the course of three very long days with three cameras all the way through. It was an incredibly thorough interview because Daniel knew that once Alexei went back to Russia, there was gonna be no pickups on this film. There was gonna be no way to say, “Oh, Alexei, can you just call in and tell us this line or answer this question that I forgot to ask?”

He spent days trying to get everything imaginably possible, including the Russian march and some of these few unsavory or challenging prickly historical positions that Alexei has taken.

Once the inspiration happened and we broke through this idea of, okay, wait, let's use the sit-down more than just as sort of connective tissue to help us understand what's happening in the thriller throughline. Let's actually delve into it as a way to get underneath this guy's skin or find or behind the scenes.

Let's figure out who this guy is through this sit-down, which was shot with three cameras, but also the main cameras, him staring at the camera across the table as though you're sitting at the bar with this guy. There's an intimacy to it, even though it's clearly very staged. It's very aesthetically beautiful and potent. It's a very weighty setup.

I went back through all the interview again, very late in the edit, which is always a great tool and practice. Once you get to sort of the latter part of a film and really you're honing in on where it's at, to go back to the primary interview — the quote-unquote “hero” interview or whatever — and go through it from top to bottom again, there are things that we've forgotten from the initial edit that pop out, oh shit, that's right. I wanted to do this or God, this great moment, or, oh my God, that insight that I knew needed to be in the film. We had totally forgotten because we were trying to figure out all these 50 million other problems!

It's context too. At that point, the things you're trying to say and you think, oh, that applies.That's right. Or oh, we have him saying it this way, but he actually says it way better two versions later. Those are the types of changes that are the last 2 or 3% of an edit that really take it to the next level, where you're finding those subtle, small nuances in the way something is said, which might actually deliver more emotional resonance than just the way that you have it in the film to communicate the what or why.

You went back and actually listened to the interview as opposed to reading the transcript.Yeah. And watched. We had the transcripts and I had been referring to the transcripts, but there's really nothing that can compare with watching and listening.

I do it often in tandem with the transcript and we'll sometimes play on double speed with the transcripts, especially through sections where I'm pretty sure we're not gonna be talking about their childhood pet or something. But as we all know, what might read great on a transcript in a script once you look at it might actually be total flubbing garbage.

Werner Herzog says that he doesn't do transcripts at all. Says they're pointless.I would agree with that about 80% of the time. What they're good for is finding specific words, but they're also good for an initial throwdown of ideas.

Paper cut?Yeah, paper cut. Usually, the best ones that I have worked with have multiple versions of an idea as opposed to this specific, over-frankenbited version to this over-frankenbited version trying to crunch the film into whatever the director or writer's idea might be.

Generally, I find that more of a selects type of script is very helpful just in terms of starting to wrangle the ideas, where it's like, oh, we're talking about this idea and these three bites from these three characters sort of circle around the idea: Is there something there? It’s the kind of script that is helpful to me in the edit.

Much beyond that and searching for specific words or phrases, I agree that transcripts are often more trouble than they're worth. If you're making a documentary that is allowed the organic time and space to become a film, if you're making a TV show or are dealing with the confines of a locked-in timeframe for post, then a strict, transcript-based script is essential.

I started my career when I moved to LA working in hardcore, industrial, E-entertainment television. We were cutting half hours in five days and hours in two weeks. The only way to do that is when you've got a locked script before you sit down to start the cut.

But that's formulaic television. That doesn't have anything to do with a cinematic experience in a documentary.

One of the things that you mentioned was that essentially the approach was a linear story, but it's not completely linear. Do you want to talk about the reasons for leaving the linear structure?I never do a completely linear structure because I don't believe life is lived linearly. Even though there's a certain linear chronology, which we are all in some ways shackled to, there are constant departures from that on a daily basis.

As much as eight hours a night, we're dreaming. What's happening in that space? That to me is where cinema is found, the dream space. If you live your life going to work and having lunch and coming home every day and putting the kids to bed, that might be your linear story.

But then what's happening in your dreams is what elevates your life to another level. It's the same thing when you're constructing a cinematic narrative. If you just stick to what happens during your waking hours, more often than not, in my opinion, it's gonna be a pretty boring movie and it's gonna be pretty boring to build.

It's only through dipping into those nether dream spaces that cinema really comes alive and that lives outside of any sort of linear timeframe.

When Navalny wakes up from the coma and they tell him he's been poisoned, it leads back to the interview and the edits seem to be done almost for comic effect. First, the edits are sentences, then half sentences, and then almost every word is an edit. Do you remember that section? I loved that. I actually went back and re-watched it. I loved the progression of pacing through that section. Can you talk about that?

When Navalny wakes up from the coma and they tell him he's been poisoned, it leads back to the interview and the edits seem to be done almost for comic effect. First, the edits are sentences, then half sentences, and then almost every word is an edit. Do you remember that section? I loved that. I actually went back and re-watched it. I loved the progression of pacing through that section. Can you talk about that?

Yeah, sure, of course. Editing is often very akin to music composition. I'm not a musician, but I'm a big fan of music. I obviously work with musicians a lot, composers in the construction of films.

But there's an element of the editing toolbox or sensibility or whatever you want to call it, which is sort of a musicality. The way we construct things to access emotion directly draws from a lot of the same tools upon which music is constructed.

The way that scene is constructed — and this was another reason why we really wanted to be sure to put a face on him, literally at the beginning of the movie — is we start the movie with this guy, we get to know who this guy is, we get a bit of his backstory, and it all builds to him getting poisoned on a plane and going into a coma and literally disappearing from the film for about 15 minutes.

We kill off our protagonist in the first 11 minutes and then he disappears. We had to be sure that we were emotionally attached to this guy and that we weren't gonna forget him and knew that it was his story, but also that we were gonna be able to sustain his story without him for the period when he's in the coma.

Unfortunately, we had a lot of other supporting characters who did that very effectively, but all of that builds up to the degree that you don't actually even notice that Alexei is absent from the story for a good 10 minutes or maybe 12. When he reenters, when he wakes up from the coma — which we've sort of circled back around to that part of the story — suddenly you realize, holy shit, this guy is back.

That's what his chief of staff is saying, “Oh, you know, he's back. It's really him.” We dispel this tension that we built of, is he gonna survive? If he does wake up, is he even gonna be able to function because he was brain dead or may have been brain dead in the coma?

You never know how somebody's gonna come out of a coma. Then, lo and behold, this guy comes out firing on all cylinders, laden with profanity, and his humor is totally intact. It had all the elements of a cathartic wake-up back in the world, thank god we have our protagonist back in the hot seat.

The way to heighten all of that was Daniel had shot Alexei walking into the bar, sit-down interview setup. He had shot it from a couple of different cameras and had him do it a couple of different ways not knowing how it was gonna fit, but with this idea that it might be a way to wake him up. He actually had that as a concept from very early on.

The first editor on the film, Eamonn O’Connor, did an amazing string out of the first pass of just work with Daniel, get all the ideas down, help Daniel express everything that he's got in his brain from shooting this thing.

Then, I came aboard. From there, it was really about just honing the timing, really finessing the musical elements of this re-entry, reawakening of Alexei, so that it had the maximum amount of emotional impact in terms of excitement and also comedy and catharsis.

I've worked on a couple of documentaries and always when I start them feel a little overwhelmed. You're thinking, I don't even know where to start if I got locked into a starting point. If I couldn't change it, what would I do? I feel like you, you just need to find a place to start. Obviously, as you just pointed out, you kind of weren't there for that section, but is it just building scenes at the beginning? Is it a question of, okay, I'm not gonna worry about the final structure, but I know there's a scene where he wakes up. I know there's a scene where his wife goes to the hospital and is turned away. I know there's a scene where his daughter gets sent off to college and you're just working in those segments.Whenever I sit down on a show and where nothing has been cut and I'm the first pair of hands on the show, I completely identify with that feeling of, holy shit, here we go again. Do I still know how to ride rodeo?

Everybody has that feeling.

Have you ever had your director draw a picture of you? This is a drawing of Langdon and Maya Daisy Hawke (the other editor) by director Daniel Roher.

For me, that first ride, what I need for my process is to construct something which may very well end up completely thrown out, but captures some sense of emotion and or magic, some sense of the electric heart of this story, whatever that may be. It's probably shorthand. It's probably incomprehensible.

But just starting the process, what is it that brings this thing to life? I need to glimpse a bit of life in it. I usually will watch and watch and watch what's there and I'll take some notes. But without any sort of obligation to construct something useful, I will start pulling together things that grab me for some reason, whatever it may be.

I did this picture before Navalny called Detainee 001. It was about John Walker Lindh, the first detainee of the War on Terror. I hadn't gotten all of the stuff that we had shot yet.

But I had a bunch of the archive. There were all these amazing shots of when this plane lands in Washington, D.C. Then, there are all these cop cars and secret service cars driving away. There's just this chaotic scene and this big parade of cars at night drives into this garage at some holding center, jail cell place for terrorists in 2001.

There was just something so evocative of October and November 2001 in this big fanfare of detention, like we got a criminal, finally we've got somebody. They go in and this massive steel garage door thing rolls down. For some reason, I had to put that sequence of archive together, which was incredibly well covered by every news channel at night. We never see who's in the car except for one glimpse with one photograph that somebody snapped.

I just like threw together this thing of all these cars, this parade of cars. Then, just as they're about to go into the garage, you can cut to the one shot that the AP photographer got of this bearded, freaky-looking character inside that all of this is surrounding to make sure he doesn't escape.

He looks like a homeless dude, like totally unthreatening. Then, they go into the garage and it's like, okay, we're off now let's put some meat on that bones and figure out what the hell is going on.

With hindsight being 20/20, with this film, if you had started on this, had all the interviews, had all the vérité, had all the archival at your disposal, what would be the first scene you would've taken to work on Navalny?

It's an abstract question, which doesn't apply in this case. There are films like Detainee or a film I did with Oliver Stone called Persona Non Grata, where you don't know what the fuck you have. You don't know what you're doing and you just need to find it.

There's the urgency to make a film because there's always the urgency to finish it, but only based on sort of the confines of the world of filmmaking, which is budgets and to get it out there. In the case of Navalny, there was a different calculus because there was an impetus from the moment this film stopped shooting, which was the day Alexei returned to Russia and was arrested.

There was an impetus to get this film done and out into the world as fast and as effectively as possible in the interest of protecting Alexei Navalny's life by raising the awareness on what he had just gone through. It wasn't a film that started with, oh, let's find out what it is. It's let's start throwing down everything that we got and see how fast we can make a great film and get it out there.

I was working on other things and wasn't available to start when they first started the edit. But literally within the four weeks after Alexei was detained, the transcripts and translations were made. Shortly thereafter, Daniel, Ed Stenson — the assistant and incredible associate editor — and Eamonn started literally just putting stuff together, just throwing down scenes.

Daniel's a very accomplished filmmaker for his young life and had been on the ground shooting it. It was very handmade and he had a vision for a lot of different scenes. Like I said, there was a central narrative that was pretty evident. It was about just starting to throw all that together.

Then, I became available for a couple of months. It was six weeks after they started and threw together what I call the vomit pass, which is often what you just have to do on something like this. I came on about six weeks after the vomit pass and then we turned it around into a first cut within six weeks after that.

That was quite honestly about 65% of the movie. It needed finesse and whatever, but it really was the story, which we pretty much knew was there. That was about the middle of July, so from July until Thanksgiving, we basically spent getting it from that 65% ‘til the end.

That was done partially remotely. We were working together in Los Angeles. Then, we went over to London to work with Maya, which was another fascinating aspect of it.

I love working with other editors. I like my ideas, but I really love other people's ideas. The collaborative process is why most of us become editors in the first place. To work with other creative people — directors, producers, and also other editors — is great because everybody brings something different to the table and says, “Hey, this is working, but what if we tried this? Would that make it better?” Then, someone says, “No, fuck, that's my idea!” “Oh, yeah, you're totally right. Let's definitely do it that way.”

One of the things that I liked was the little revelations of character around some of the sit-down interviews where you either held before or after Navalny starts to speak. He would say something, stop speaking, and yet we're still on him. Can you talk about pacing that and the value of holding on someone after they finished speaking?Sure. For a lot of years, I was really into really fast editing. Cuts-per-minute in a beats-per-minute mentality.

That's all that ET training.Well, it's MTV training, man. I grew up in the ‘80s. I never wanted to work in E-entertainment television.

They were the only place that would hire me when I moved back from Chile. The first time I discovered editing was Natural Born Killers. I was thinking, “Holy shit! That's where a movie's made.” Then, I did a lot of studying into older shit, but always was fascinated by the speed of the cut.

It took me a long time to sort of come around to the revelation, which is so obvious that if you slow down, people can actually feel something. I made a couple of pictures with Abel Ferarra. As he likes to say, “If you're bored, slow down,” which is a great insight because truly if you're going so fast, a lot of times there's nothing for you to emotionally hang your hat on and it just gets boring.

If you slow down, suddenly you got something you can look at, something you can feel and you wanna find out more and, lo and behold, it's no longer boring.

Over the years, I started playing with that, investigating with that, internalizing that. Then, it was probably on a picture that I did with Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato called Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures.

On that one, we really played a lot with expressions in sit-down interviews because it was a highly archive-based show. Mapplethorpe obviously was dead. We had audio recordings of him, but there was no narrator. It was an HBO show.

The narrative was constructed verbally through these sit-down interviews with these incredibly wonderful characters who knew Mapplethorpe in New York in the ‘70s.

Their expressions before and after answers or in between answers carried so much emotion that we started really embracing those moments and letting people sit longer because there was comedy in what they would say and how they would react once they were done answering if you actually just left the time for them to react to themselves.

At this point, it's kind of standard procedure to be looking for things that are the outtakes or the slightly more off-camera moments. But actually working with those expressions the way that you would work with actors’ reaction shots, it's a really fun and fascinating and sort of a different way to deal with interviews rather than just using them strictly based as for their content and delivery but actually as character moments. Then, you turn interviewees into characters.

I did an interview a while ago with somebody, a director, that pointed out the difference between skating over a scene and living in the scene, that that’s the difference. It can be more boring if you just skate through the scene, if you get through it as quickly as possible than if you take the time to really feel something in the scene. Speaking of that idea, I love the little scene of feeding the donkey, but clearly, that scene to the plot means nothing. Talk to me about the value of caring or feeling or whatever you think the reason was for a scene like feeding the donkeys.

I mean, donkey pony was totally essential to the plot, in the sense that from a very practical standpoint, it was Alexei’s recovery. He talks about that. It's his taking a walk with his wife every day as part of his PT. There was at one point where we had a whole throughline of his physical therapy and his recovery. He does exercises and all this.

He came out of a coma and the reason why he stayed in Germany was to recover physically so that he had all his strength to go back to Russia, which we didn't really identify until later because specifically if he were to be thrown in prison, he wanted to have enough bulk on him and enough muscle tone that he would be able to survive the solitary confinement that he's currently enduring.

If you look at him now, he's a very gaunt figure, but imagine if he had gone back before he had done all that physical training. On a very superficial level, there was an essential reason for the donkey pony scene to be in there. That's not why the scene is there. The scene is there because it's one of the earliest and most essential scenes of his relationship with his wife.

Their banter is totally revealing about not only how they interact as a husband and wife that challenge each other, that neither is subservient — they're both taking the piss out of each other and, in that way, probing each other and pushing each other on and laughing through it all and using humor as a way to dissipate the tensions of this incredibly difficult situation in which they find themselves and a world in which they find themselves as high-profile political figures, opposition figures — it's also a very deep insight into Alexei's character as an individual.

That is a throughline all the way through the picture, of his dealing with struggle through humor. We have a lot of laughs in the picture before that, but it really drives home this feeling of, oh, okay, as serious and intense as the subject matter is, the filmmakers are aware and give us as an audience permission to laugh because the subject himself is laughing and taking the piss.

If we don't laugh our way through these most serious of situations, we'll never survive.

One of the things that the film hinges on is there's the huge vérité scene of the phone scam, where he decides who's gonna call these guys that he thinks might have poisoned him. You think there's no way, there's no way he's gonna get anybody on the phone. And if he does, there's no way anybody's gonna talk. It becomes a core moment of the film. Can you talk about constructing that and building up to it?Alexei and Christo — the journalist from Bellingcat who did the investigation to identify who these FSB members were and found their phone numbers and sort of devised the technical means by which to contact them and all that — and Alexei's team, specifically Maria Pevchikh, who were the three main characters who were involved in that morning of making these phone calls — they all knew that there was a very, very small chance of getting anything out of it and that any of these trained assassins are part of the military intelligence of the Kremlin.

So no one would think there's no way they're gonna fall for being duped or gonna say anything. The first approach was Alexei calling and saying, “Hey, this is Alexei Navalny. Why'd you try to kill me?” Not surprisingly, they all hung up. Then, they figured, let's try this other way and pretend to be somebody else and try punking them.

The first one recognizes Alexei’s voice and hangs up on him. The second one is a chemist who didn't probably have nearly the amount of military training as the others. He totally falls for it and thinks that he's talking to some senior-level person in military intelligence and that he has to deliver a report.

He does and talks for so long. That phone call’s about six minutes in the film, but it went on for about 45 minutes. By the end, Alexei and Christo leave the room and go to the bathroom. They were all bored. They were like trying to figure out what to ask this guy because, by that point, he was all chummy with them and volunteering information.

We knew obviously from the get-go that that was a centerpiece scene because the confirmation that it was a Kremlin-organized hit on Alexei is a shocking revelation.

There was an initial cut of it, which was way too long and they made a lot more calls that were dead ends before the Kudryavtsev call. But in that case, that's the kind of scene where from the beginning of the edit that it's gonna be in the film and it's gonna be a centerpiece and it's a big production number.

In some ways, it's about throwing down a first version of it to start seeing, getting enough of it on its feet and then you just leave it because you know you're gonna come back to it. You have to make it rock and roll and shine and be fantastic, but that's just crafting.

In a scene like that, you're not gonna intercut it. You're not gonna leave. It's a very vérité, in-the-moment, watching history unfold in real time, quote-unquote “type of procedural.” Our job as editors is just to craft it so well that you don't notice the editing.

As an editor, I didn't realize how much that was crafted from a 45 minute phone call. You watch a scene like that and you don't think what the other elements are that could go into it as an audience, right? There could be more dead ends. How many of those do you want?

You said you put in a bunch of 'em and then called someone. I pretty much had it by the couple that didn't work out. I thought, okay, I'm not expecting anything from this, so I don't need any more of these failures. Then, I didn't realize that that conversation went on so long.

I felt like I just saw what they got on the phone. That's amazing.

As an editor, I didn't realize how much that was crafted from a 45 minute phone call. You watch a scene like that and you don't think what the other elements are that could go into it as an audience, right? There could be more dead ends. How many of those do you want?

You said you put in a bunch of 'em and then called someone. I pretty much had it by the couple that didn't work out. I thought, okay, I'm not expecting anything from this, so I don't need any more of these failures. Then, I didn't realize that that conversation went on so long.

I felt like I just saw what they got on the phone. That's amazing.

That's interesting because there were two elements to that, which we had in mind. One was, as soon as the phone call happened, there was this very real world discussion about, okay, what do we do with it now?

The decision was made by Daniel and the production team that we're making a documentary about this and it may be our cameras that have shot it, but this is essential for the larger impact of freedom of speech, democracy in Russia, human rights, and a whole lot of real world things that go far beyond the filmmaking team.

It was agreed immediately that the Anti-Corruption Foundation, Nalvany’s organization, would be able to use the footage and release the calls as soon as they wanted to in the interest of trying to build pressure on the Kremlin. By the time we were in the edit, a very long version of these phone calls already existed on the internet for anybody to see.

When you're dealing with something like that — which had millions of views, it was a massive news story when it happened, especially in Russia and Europe, but even in the U.S. where sometimes we care about things like that — you sort of wonder, okay, you know, it, you just have to think to yourself, does it matter? Has anybody seen it? Do you build it for people who have seen it or for people who haven't seen it? You try to make it relevant for both.

Then, the other thing was, how much editing goes into a piece like that? It's interesting that you felt like you didn't see it because there are a lot of crosscuts and non-continuity moments that are specifically left in that edit because I didn't want to pretend that it was not edited.

I definitely got the sense that it was edited. You cut to the woman with the phone, shooting it, you cut to expressions, people can't believe that you know what's happening. But I didn't realize how much longer the phone call was. That was something I never saw on the internet and never felt in the edit.

I definitely got the sense that it was edited. You cut to the woman with the phone, shooting it, you cut to expressions, people can't believe that you know what's happening. But I didn't realize how much longer the phone call was. That was something I never saw on the internet and never felt in the edit.

I appreciate it because what drives that is the emotion. There's an emotional continuity to that scene because there are lapses in time and things that may not have joined up in reality, in chronological reality.

They are an emotional continuity that just draws you in and you believe that it's happening and in a space that's all its own. That's what I find fascinating as an editor is to get into that zone, cut a scene, and then, by the end, it's built in a way that you don't notice the editing.

I'd heard that term before, but I really love the idea of emotional continuity, that the cuts themselves — if they're not continuous or if there's a jump or something like that — don’t really matter because the emotional continuity is there.It's really all that matters in terms of constructing cinema. If somebody's paying attention to the fact that somebody's hand position doesn't match from one shot to the next, then it's not a very well-cut movie.

I wanted to quickly about pacing. You explained where you're jumping through time, where a 45-minute phone call happens in six minutes, but there's other moments that are held or drawn. I'm thinking of the airplane as Navalny is flying back to Russia at the end. You get that sense of a thriller, of the building to a climax.

That was a huge production number, so to speak, for a documentary. It was really fun to cut. Again, there was a first version of it laid out and then it was about really honing in the balance between what's happening on the ground, the repression of the protestors on the ground, and the expectation and the glimpses of hope that all these people who showed up who were not rabid political figures or protestors.

These were normal, everyday people who showed up because Alexei coming home represented the hope for healthy democracy in Russia. Those were the stakes. Then, to be on that plane, that was an absurd scenario. The only people on that plane, aside from Alex and Yulia, his wife, were journalists.

Every seat on there was bought up by a news agency. There were just cameras everywhere to the point where — we didn't include it, but the pilot's saying, “If everybody doesn't sit down, we're gonna land this plane until you do because I can't have all these cameras.” All the aisles were blocked. It was chaos.

But within that, we had two cameras of ours on that plane. The intimacy of what was going on in Alexei Navalny’s head, in his mind, in his holding of his wife's hand, and Yulia's look at him amid all of this chaos spoke to the hope that it represented for a large part of Russian people and the sacrifice that almost certainly was involved in the eventual arrest, if not worse, that was gonna happen as soon as they touched down.

That internal emotional life of that scene was so rich. It was just there in the way that he looked out the window. That was not a scene. That was a procedural scene that you wanted to just get through because yes, he goes back to Russia done, he gets on a plane, the plane lands, he gets arrested.

What's actually happening there is somewhere between a hero's return and Icarus flying too close to the sun. I want the audience to be able to have time to swim in that contradiction and emotional challenge and have time and space to reflect on their own life in that context.

Can you talk about the choice to intercut back to the team in Germany as he's being arrested?

Well, they were watching and it was a triangulation of events. I just spoke to two of ‘em, but the third element of that triangle was his support team in Germany. For the cause, so to speak, the important thing was that Alexei went back. At that point, it was not necessary nor was it wise for his entire support team to go back.

His chief of staff was Leonid at the time and Maria Pevchikh was his investigative right-hand partner on most of the investigative work that he's done. She's now his chief of staff actually and head of the anti-corruption foundation. It would've been foolish from a strategic point of view for them to go back and him to not only have the head cut off of the organization, but also the lieutenants would've been absurd.

They were obviously emotionally so connected to it. Christo, who had been a central part of setting all of this in motion and being a part of the film and the investigation and the revelation of the poisoning, was watching it from Vienna. It was about tying events that happen on the ground in Russia to the rest of the world and the outside world and this amazing ability to live in events worldwide in real time.

You have TV reign broadcasting from a cell phone in the middle of the throng of people and getting arrested at the airport. But that transmission being watched in Western Europe — that's the power of where communication technology is right now, which makes something like Tiananmen Square in the late ‘80s impossible to happen because autocrats can't get away with the time delay of footage of an event like Tiananmen Square happening and then having to be smuggled out of the country and the two-day delay of it having to be flown over the ocean and then finally broadcast.

Nowadays, we can watch it live. The world's response and accountability — we can talk about questions of effectiveness — but the actual what's happening is no longer a technical challenge.

That's what we saw in the Gulf War, in the war in Afghanistan — this idea of embedding journalists so that the wider public doesn't get to see what actually is happening is the way governments around the world control information and make choices without necessarily having to have accountability.

Talk to me about the creative choice of dropping the sound out as Navalny is arrested.

It was an emotional vacuum. Amid all that chaos that we had been building to, living in the screaming guitars, everything was going on, the screaming lawyer saying “I've got all the evidence,” and the horrific Stormtrooper-esque customs officials, all within this confined space of a visa border space with the cameras — it was all claustrophobic and chaotic and dystopian.

All of that was building to the point of no return, where it was clear that the lawyer was on the other side. She had already entered Russia and the stormtroopers weren't gonna get up, live let up. They weren't gonna let Alexei through.

That becomes clear in his expression and Yulia, his wife's, expression. Once the fight is done, it was about opening up a little emotional space to say goodbye, basically. It was the parting of this husband and wife. It was an admission that, okay, I've lost this battle.

It sort of is an echo of what Yulia said at the Academy Awards: “Stay strong, my love.” At the core of their story is this incredible love story. It's a very tragic emotional moment for them as individuals to be separated.

The power of sound, to create chaos and envelop a chaotic emotional moment, can also sometimes be heightened by just pulling the sound out. Especially when you watch that scene in an audience in a theater, it's stunning. We mixed the movie at Skywalker Sound with an amazing team.

We worked very hard to have big sound and to sit in a theater filled with people and all the sound goes out — what you hear in that moment is the music and your neighbor breathing. It creates an emotional intimacy that is so immediate, that ultimately we hold that as Alexei is hauled off.

Our camera guy was amazing. He's literally standing in the visa, this claustrophobic space, pans around with Alexei getting taken off on one side, spins around 360, stops, and captures Yulia on the other side having just gone through the passport control.

She looks back. The camera guy lands and pulls focus just as her eyes see her husband for the last time. She turns and walks off and then we cut to her going down this long tube of an escalator, where there's nobody else because everybody just seizes part for Yulia to pass.

Then, we bring the sound back in, as with the papers ruffling of the next guy in the customs place, letting her through and saying, “Good luck to you and to your husband.” It's a very emotional scene and pulling the sound fully out of that was a big part of it.

To wrap up with a continuation of emotion, I loved coming back to the donkeys. Talk to me about the value of that and choosing to do that.

Yeah. That was the brilliant insight of producer Diane Becker. We were sitting in the edit and the end was pretty much in shape. We were still shaping a little bit. We were still crafting the end.

At one point, we got a call from our camera guy, Niki, in Germany. in Austria. He said he and producer Odessa Rae were going to go and meet up with Yulia and Zakhar, Alexei’s son who was studying in Germany, and Dasha, who was on spring break or something from Stanford visiting her brother and mom in Germany.

They were all gonna get together and go back to the town where Daniel and Odessa had started shooting with him. It was one of those things. There was not really any prep. It was just, “Hey, Yulia’s around with the kids, we're gonna go shoot 'em.”

Diane said, “Go shoot donkey pony!” We were sitting in the cutting room and it was one of those light bulb moments, where we said, “Exactly! Go shoot donkey pony!” We wanna see where the kids are. We wanna see at the end of the movie that they're okay and that Yulia’s okay and that as a family unit, they still are smiling. They still have their humor, which is what Alexei left them with, obviously.

But Alexei is absent and his little pony has that last look. Again, there's an emotional connection there because, in the earlier scene, there's this whole banter between him and Yulia about his pony being better than her donkey.

When he’s not there, the pony is sort of his stand-in. Again, it's an emotional moment, but to me, one of the most fascinating parts of this whole project was, in the edit specifically, the emotional balancing act/contradictions and exciting diversity between the humor and laughs and the emotional pathos. Those two things really feed each other.

When we would screen the movie, people would come out and say, “God, I had no idea it was gonna be so funny.” Or they would ask in a Q&A, “Why did you make it so funny?”

It's not that I made it funny. It's that it wanted to be funny because of how absurd so much of this is and how Alexei deals with the world and how these mortal threats like Christo being on a kill list and yet manages to have his humor as he can't return to his home and is forced to live outside of Europe away from his family because there are assassins running around Europe ready to kill him.

The stakes are so high that the only way anybody who actually is trying to take on authoritarianism can survive those threats it seems is with humor. Narratively, humor unlocks the emotional access for the tears. That was one of the most rewarding parts of crafting this picture: to access the emotion of humor and let that build to the emotion of tears.

That's a great place to end this interview. I really thank you for your time, for your expertise, and for allowing us your insight into this great film. Congratulations on your work.Thank you so much. My pleasure.