Weird: The Al Yankovic Story

ACE Eddie Award winner Jamie Kennedy dissects the satirical biopic and her eye-opening take on how you should deal with notes.

Today we’re speaking with Jamie Kennedy who recently won the ACE Eddie for Best Edited non-theatrical Feature film for her work on Weird: The Al Yankovic Story.

She’s edited the feature film Blueprint, and TV shows like The Summer I Turned Pretty, On My Block, Love, Victor, Die Hart, and Flipped. She was also an editor on Modern Family after several seasons on the show as an assistant editor.

Weird The Al Yankovic Story with Eddie winning editor Jamie Kennedy

Congratulations on your ACE Eddie!

Thank you so much!

I wanted you to talk about montage. There's a great “My Bologna” montage at the beginning. Was that planned as a montage?

This is really interesting. That scene's broken down into two different parts, where Al’s having the inspiration to come up with “My Bologna” and he's hearing “My Sharona” on the radio and he’s seeing the packet of bologna on the counter and he gets the inspiration to suddenly start playing his first song parody since he was a child.

There's that part of the scene and at the tail end, he goes into a montage where he's writing it, he's sending it off to the radio station, and that was actually a scene that was split between me and the additional editor on this film, Peter Dudgeon.

I did the first half and then Peter took over the physical montage part. We talked about that because this was a very planned out movie in how they shot it. They had 18 days to shoot everything. People are always asking, “There must have been so much improv ‘cause you have Jack Black and you have Rainn Wilson. There must have been so much improv on sets.”

Nope, there was no time for improv. Everything was scripted and the script was just that good that it didn't need an additional punch-up. It was great to be shot as is, so there wasn't a lot of freeform that was going on except for that one scene.

Nope, there was no time for improv. Everything was scripted and the script was just that good that it didn't need an additional punch-up. It was great to be shot as is, so there wasn't a lot of freeform that was going on except for that one scene.

I'll say that the scene where they're recording things in the bathroom — that was their first or second day of shooting, where they were blessed with a little bit more time on that day than any other day. They were able to keep the cameras rolling and they got just like a lot of B-roll of setting up the tape recorder and starting to play in the bathroom.

That was a lot of footage that we got, but because we were moving so fast, I was working on other scenes and Peter took on the montage part and he said, “It's kind of fitting that I did this,” ‘cause he comes from like the world of Kathryn Bigelow and he assisted Billy Goldenberg for many, many years. He's used to sifting through a lot of footage and picking out those moments and he did such a great job with it.

He did a first pass of it. I went through and then tightened up a couple of things and had a couple of things hit in different ways. But after our kind of co-polish on that scene, that montage kind of stayed the way it was through the end of the movie.

It's interesting ‘cause we come from montage in two different worlds, where he comes from his mentor on that, but I also studied under an editor, Tony Orcena, who comes from the school of Hank Corwin, who is maybe arguably the king of montage [laughs]. I feel like there's been some trickle-down things that I've learned in that way.

He was always teaching me how to string everything out and go through and find the little moments. It's always the moments you're least expecting and playing things against each other and seeing how they fit and finding the art in the jumble for that.

I've talked to Hank about his early experience as a TV spot editor and he said, “The only thing I had to edit was the leftover prints from those things. Just as somebody drinks the Coke, I don't have the Coke drinking. I've got the other crap that's around it.”

Yeah, Tony worked with him at Lost Planet and so he'd be doing Gatorade commercials, where he’d say, “Tony, find me every single B roll item you can find of lions running across the Serengeti.” “For Gatorade?” “It's gonna work!” [laughs]

That's classic. You mentioned how short the schedule was for shooting. What was your post schedule like?

They shot it in 18 days. 10 days later, I turned over my editor's cut. We churned through it and got it out. This was the insane part, but originally, they were only gonna give Eric two weeks for his director's cut. He said, “We have to draw the line here. In a normal movie, I get 10.” So we compromised to 6. They gave him 6 weeks of editing. That was our timeline for the director's cut.

The day we turned in the director's cut, Al went on tour actually, so because of the timing, he wasn't able to come in and work with us in the office, but he was sending paper notes along with the other producers.

They started shooting it beginning/mid-February of 2022 and we were locked by the first week of June, mixing it mid-July, and it came out in November. It was quite the turnaround, but I love it because I've come from TV primarily before this.

This is my first solo feature and it's definitely more of the timeline that I'm used to working with on the shows that I work on. I was thinking, “Yeah! This is fine. I have more than two days to do my editor's cut? Child's play. I could do this.”

“I normally only get four days with a director in TV.”

Exactly! What are we gonna do with all that time?

Did you do temp music?

Yes. It was a lot of experimentation we did with the temp music because originally, while we were working on the assembly and the editor's cut, I get a text from Eric, the director. He said, “OK, so I was thinking for temp music, what I'd really like to work with for score is all John Williams scores. ‘Cause John Williams is such an important part of the Al story ‘cause the saga begins, you have Yoda, you have Jurassic Park, all of these songs about movies that John Williams scored. I think it would mean a lot if we use all John Williams scores.”

I said, “OK! We can do that.” Peter pulled every John Williams score he could find and then we realized, shoot, that's really hard to temp with ‘cause John Williams is very specific. You can get very specific swelling moments, but there's a lot of subtle moments in our movie too and suddenly this whimsical, bombastic nature clashing against everything, but I thought the number one rule is hand over what they want.

Don't fight it, you have to try it, and then if it doesn't work, we'll discover that together, but I'm never gonna tell someone outright that it doesn't work. We went through the deepest of cuts. I put a track from Sabrina under the first Madonna and Weird Al scene.

It was deep, deep cuts. We went through Hook. Hook was a good one ‘cause there was a lot of little subtle pieces in Hook. We scraped the bottom of the barrel for every variance in a John Williams score we could do.

We turned it over and Eric said, “Yeah, I might have given you the wrong direction. I don't think this is really working.” That's okay. We had also muted some alts that we put under. Working together with Eric, we then sort of started to realize, okay, wait, you know what this score actually is? It's more Alan Silvestri. It's more Forest Gump, which is also a Weird Al song, so that also was fitting.

Then, once we started temping in more of the Alan Silvestri feeling, that's where we found the tone of the score for the movie, at least the biopic-y parts of the movie. Once you get into the action scenes, then we're temping in John Wick. We're temping in various action movie soundtracks.

I used Independence Day in the mid-credits scene that we used. It was much more of a modgepodge once you get into the different genres that we're bending. But Alan Silvestri was the sound that we found. Then, we have two great composers, Max and Leo, who worked with Eric a ton before, including on Die Hart, which I cut with Eric on. The one with Kevin Hart, not Bruce Willis. They came in and made everything sound their own. When they brought in an accordion artist and put the accordion themes into things — if you listen very carefully in the diner fight scene, there's this frantic moment where it's all accordion music and it's amazing. That's how we blended to find the sound of our movie.

The movie obviously plays on a lot of movie tropes, so you want those trope-ish musical sounds, right?

Right, exactly.

Jamie with her ACE Eddie

John Williams is perfect. For one of the movies I edited, I made a T-shirt for the post crew with 10 Commandments of Film Editing. One of them is “Temp not with John Williams. He composes not for thee.”

[laughs] It's true. Don't start with the master. He said it’s not gonna work out for you.

You could though ‘cause you were going for those tropes, but it's interesting that it didn't quite work for the director, even after he asked for it.

The one we did keep — because this was what he always pictured was during the LSD trip scene — I had put in actually a Weird Al song, an instrumental for it called “Nature Trail to Hell.” That was my deep cut that I brought to it. I thought, oh, this is gonna be great. He's gonna notice that it's a Weird Al song and it's working perfectly.

He said, “It's working, but I always pictured ‘Duel of the Fates’ in this scene.” I said, “Alright! We'll put ‘Duel,’” and it worked. It stayed up right up until they recomposed over it, but you can kind of still hear the roots of “Duel of the Fates” in there.

Did you watch the editing of any of the scenes you were parodying?

Oh, yes, very much so. This is a horrible confession, but I had never seen Boogie Nights before working on the movie. When I learned that the pool party scene was Eric's dream to parody Boogie Nights — he said, “When I wrote this, I was picturing that pool scene” — I thought immediately, “All right, gotta watch that.”

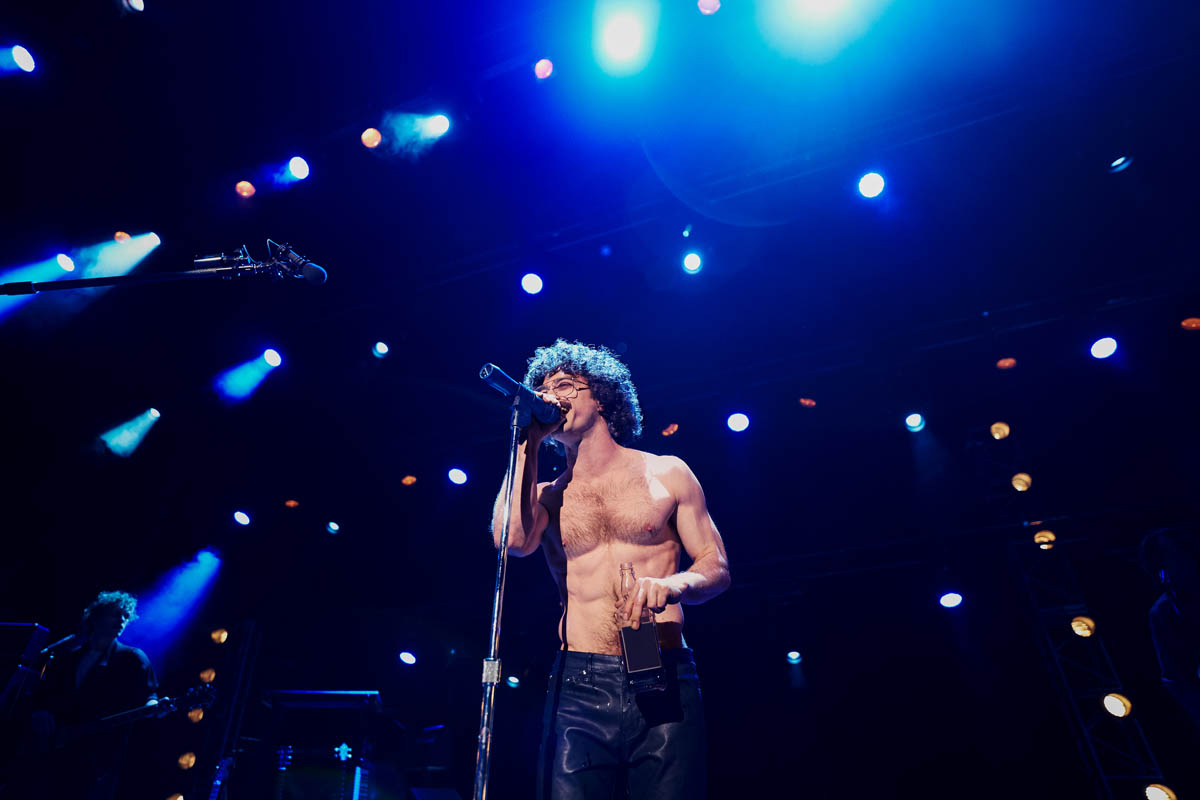

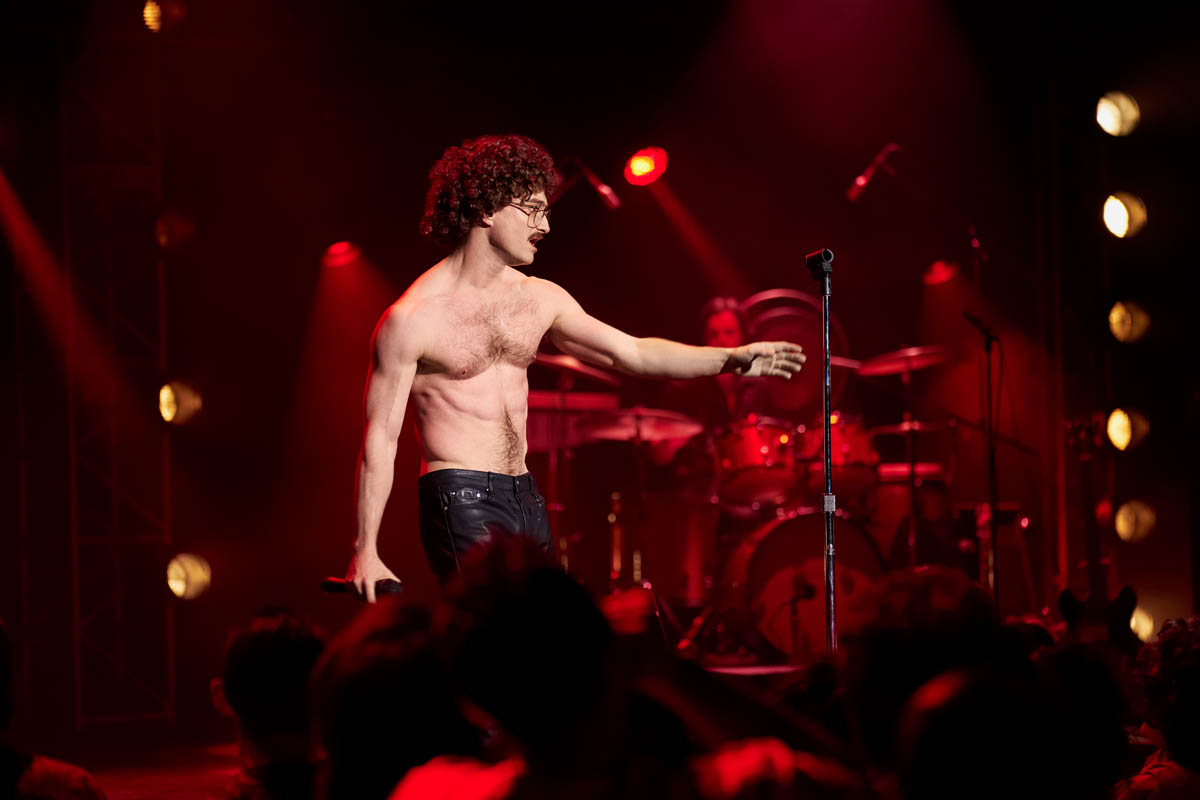

I pulled up the Doors for the post-“Like a Surgeon” performance when Al is berating the audience and eventually gets arrested for indecent exposure. That one was probably the scene that I tried to mimic the closest in terms of cutting patterns, ‘cause it again is a very unique feeling and you had to kind of evoke the same style they were doing, where it's cuts in between lines, going behind, and continuity not totally mattering but just trying to feel the movement that he's creating in this chaos.

That one I really tried to emulate in my cutting pattern as well. The one I didn't catch was the mid-credits scene when Madonna goes to — spoiler alert — Al's grave. When I read the script and when I watched the footage, I had this very specific idea in mind — and that's why I cut it with the Independence Day theme, this big swelling moment that turned into a horror thing.

Then, when we got into the director's cut stages, Eric said, “Oh, actually, we need to stretch that out because it's supposed to be the ending of Carrie.” I said, “Ohhhh, okay. That was one that just entirely went over my head when I was assembling it.”

We then had to go back and watch the ending of Carrie and I thought, “Okay, yep, yep, yep, we're doing it. We got it.” But then, our cut overall was way too long. That first version was a solid minute and a half long. This is the mid-credits scene. Our movie's too long, so then it just got trimmed up into what it is.

Deciding on the length of sequences and how long to stay in a specific storyline, there's scenes, but then beyond scenes, there's kind of these longer sequences, almost a reel. Was there a feeling of needing to keep the macro pacing the same or different or thinking about the lengths there?

The biggest challenge we had was the first act ‘cause we had Al’s childhood section, which comprised of two kid versions of Al. I think in my editor's cut, the first time you saw Dan Radcliffe on screen — besides the cold open of the movie — was 15 minutes into the movie. We thought, this is not good.

The audience is going to come for Dan as Al and the more we are staying in any world that's not that — as funny as it may be, the parents are so good and the scenes are funny — but if we are gonna lose people — especially we were always clocking the fact that this was gonna be for Roku and that Roku has commercial breaks and they mentioned the first commercial breaks come after the first 10 minutes of the movie — if people have gotten to the first commercial break and Dan Radcliffe has not appeared on screen yet, we're losing everyone.

That was the one that we were most hyper-focused on winnowing down the first act of the movie, just to get to that point. That was where we spent the biggest chunk of our time. That first dinner table scene with young Al and his parents, there was a much longer monologue from the dad about losing his hand and the guy who died in the factory that day.

It was all so funny and so well-delivered by Toby, but we had to just hyper-pick it apart and pace it up because we needed to get to that point. Then, we did measure everything in what jolt of energy was. I think that was kind of how we were tracking everything, like when is one the next jolt of energy.

We got through the beginning. We winnowed it down. It's now a very manageable amount of time. Now, we have the biopic part of the movie and that carries itself pretty well. There's three musical numbers. It's keeping everyone's attention up. But then, we thought, the next thing is we need to get Madonna in as soon as possible.

It became then, “Okay, how do we pace things up so that we get her arrival a little bit quicker?” Once you get to Pablo Escobar, the rest of the movie kind of just sings. What was really interesting, since we were a complete remote production and pretty low-budget, we didn't have the opportunity to do any test screenings for our movie.

We would have friends and family just come into the office to watch it, and see what they laugh at. There was a lot of trusting our gut and if we believed that a joke was funny, we had to say, “No, it's gonna be funny. We have to believe in it.”

But we did notice the only thing not having that barometer to measure things against is the first time we had a big screening was at its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival. It's 2:00 am after the movie and Eric and I both turned to each other and we said, “Man, it kind of dragged in this one specific part that we thought this part would play so well.” When we would play it for like two to three people, they'd say, “It's perfect, don't change anything.”

Then, suddenly we're sitting in an audience and they didn't laugh for a little chunk of time and we thought, if we had known that, we would've paced up that little piece as well, given the burst of energy that we were looking for.

But once you get to that point, there's no going back.

No, no, no [laughs]. We stood behind it. It was the movie that we wanted to release into the world, but we did have that mutual moment of we felt it, we didn't feel it before now, but now we felt it.

That's so interesting on screenings, isn't it? That you get in with an audience. You don't need notes. You don't need anything. You just literally feel the audience around you.

Yep, which is amazing for the rest of it, because again, we were a movie that went right to Roku, which is great and were so supportive and they were the people who took a chance on this movie and made it happen. But I tried to make it to every screening I could go to of the movie ‘cause just feeling the energy from the audience was incomparable to anything.

Beyond looking at the couple of parodies that you had to do, was there any other research that you felt you needed to do?

Not particularly. I've been a huge fan of Weird Al my whole life, like circa eighth grade when my fake high school boyfriend gave me a mix CD with Weird Al on it. My husband is such a big Weird Al fan. We've gone to every concert that he's done out here prior to the making of this movie.

There wasn't anything I felt like — not that it would've helped, considering how much of the movie may or may not be true about his actual life.

Wait, that was Madonna though, right?

Yeah, yeah, yeah [laughs]

I had seen UHF, but I didn't rewatch it before I started because I also knew it was going to be a different kind of humor and a different kind of cutting pattern.

Eric was always so determined that the theme of our movie was gonna be grounded, that the humor of our movie was gonna come from grounding it in as serious a nature as possible. He wasn't interested in jokes that were “haha funny” jokes. He was interested in you’re laughing because this is a subversion of what you're expecting from a Weird Al biopic.

So keeping that in mind, I'm thinking, it's not gonna be helpful for me to rewatch UHF because I'm gonna be trying to copy something that doesn't exist in our movie.

That became a big part of our editing process too. As we were trying to cut time, as we were trying to make things sing a little more — no pun intended — we would stop on jokes and say, “Is this a joke that is winking at the audience or is this a joke that’s too broad?” and we cut them out.

There's one joke in the original teaser where Al says, “Someone give me my accordion,” and three accordions come out from each side of the screen. That's not in the movie and it was a huge point of contention ‘cause it was Al's favorite joke in the script, but Eric said, “This wouldn't happen in real life. There wouldn't be three accordions suddenly coming out of nowhere to be handed to this person.”

So ultimately, the compromise was: it's in the teaser. People will know it existed. People can laugh at it there, but in the world of our movie, we just can't have it anymore. We just use the one alt where he just says “Get me my accordion” instead.

Let's talk about the particulars of pacing and rhythm in comedy.

I had one of the best mentors in the biz, Tony Orcena. We worked on Modern Family together, where he brought me up on that show. I followed him around as his AE for many, many years.

His favorite saying that he always told me was that “Oxygen fuels fire and kills comedy.” That's always the credo that I have followed.

I'm gonna make a t-shirt for you with that saying on it.

[laughs] I will wear it. It’s really true. The more air you have in something — it seems so simplistic to say it that way, but it's not — snappy and keeping things going is what makes comedy. Playing jokes on screen is what makes comedy.

[laughs] I will wear it. It’s really true. The more air you have in something — it seems so simplistic to say it that way, but it's not — snappy and keeping things going is what makes comedy. Playing jokes on screen is what makes comedy.

The big difference I think between drama and comedy — they're not an interchangeable craft, I think anyone can cut anything — but with drama, you're playing things on faces and reactions. With comedy, if you're not playing the joke on screen, then the audience is losing that. They're losing a very key part that they're laughing at, so it's always to the best of your ability, you should try to play jokes on screen.

There's also kind of an interesting art to the rhythm of comedy. Comedy's subjective, but there's something so universal about what people expect in a comedy. There's something interesting in the fact that if you follow the patterns of cutting comedy — you keep it moving, keep it well-paced, keep the action on what's supposed to be seen at any point in time — people will laugh at something, even if it's not the funniest joke in the world.

Because we're just hardwired to think that that's funny. Sometimes, you can use your tools as an editor to help sell the comedy of something that maybe isn't the funniest thing in the world. I'm not saying that about any particular thing I've worked on, but… [laughs]

In comedy, often, the cut is the punchline.

Exactly.

Specifically, can you think of a pacing thing from Weird that you can talk about?

Some of my favorite editing humor is when you linger a little too long on something, which is the opposite of keeping it fast and moving. But when you keep people moving, moving, moving so that you then get to stop down for an awkward joke, that's always really funny to me.

In Weird, I think one that really always kind of plays so well and that I love is at the pool party, when John Deacon introduces himself and he says, “I'm John Deacon.” Pause. We see someone and Dan says, “Who’s John Deacon?” “He's from Queen.” Pause. “I play the bass in Queen” and then everyone reacts to that.

I think that's the perfect settling in. The audience is also probably thinking the same thing at the same time, so you're allowing them to catch up with a joke. That's giving you a permission to stop down for it as well.

There's a cut earlier on when Dr. Demento says that he wants to be Al's “dee-mentor,” which wasn't intended to be a Harry Potter joke, but works [laughs]. There's this uncomfortable hold on Al's face reacting to that because again, the joke isn't exactly that funny. It's just a cheesy play on words, but it's the choosing to be on him reacting to that that's kind of that editing punchline versus the joke punchline.

Isn't there another one? I was thinking about the same one with Dr. Demento where he says, “Al Yankovic is too long.”

“Weeeird Al.” I love it [laughs].

Great moments. How did you get this gig? Obviously, your comedy background. They must have been looking at that.

This was literally a dream come true situation. I met Eric when I worked on Die Hart. I had done a show for Quibi — rest in peace — called Flipped. I was looking for my next show and my post producer from Flipped moved on to Die Hart because they were both for Quibi. She literally called me up and said, “Hey, I'm doing a new show. You're starting on Tuesday.”

I’m thinking, great, love it, no notes, I'd love to work on this. She said, “I'll set you up with the director just so you can guys meet on the phone.” We hit it off. We started working on the show together.

About halfway through the post process, we were just hanging out in Eric's office. That's when I learned that he had made the original Funny or Die fake trailer for Weird that starred Aaron Paul. I don't even know how it came up, but I lost my mind. I said, “Eric, this is literally my favorite YouTube video ever made. I can't believe we've been working this long and I didn't know you'd done this. I love that video so much.”

He said, “Oh, well, you know, Al and I have been trying to make it into a feature for a long time.” I said, “Yes, please sign me up. I would like to watch it. If you ever make it, please hire me to edit it.” He said, “I definitely will.” I said, “Great.”

Then, cut to two years later, post-post-quarantine, I was working and he sent me a text. He said, “Hey, give me a call when you can.” At the time, I thought he was texting me about a Die Hart 2 for Roku and assumed he was texting me about doing the second season of it.

So I text back and I said, “Hey, is this a Die Hart 2 text?” He said, “No, it's a Weird Al Yankovic story text.” I have never called back someone quicker in my life [laughs]. He said, “Yeah, it's happening. Roku's doing it. Are you available?” I said, “Yep, done. Whenever it starts.”

Are you available? You only have to block out two months.

Yeah, exactly. You'll be able to do your summer project, no problem, which is exactly what happened. I was doing season one of a show before he called me, we did Weird, and then I was able to hop back onto season two of that same show.

That's so fast. That’s crazy.

So fast.

You’ve done a bunch of shorts. Why?

There's so many stories of people who meet people through doing shorts, like they were roommates in college and it was Wes Anderson and the Wilson boys. These earth-shattering moments where the right people met and were able to collaborate from there.

I can’t necessarily say that that has been any kind of value that's come from the shorts I've worked on. I've probably almost never been paid on any of the shorts that I've worked on, short of a couple of examples, but they were all good people. They all became good friends, so they were at least good relationships.

But most importantly, the shorts came at a time when I was still working as an AE primarily. Even though I was like cutting scenes for the shows I was working on, the shorts were my opportunity to flex my editing muscles by myself. It was giving me practice that I wasn't necessarily getting in my day job to become a stronger editor.

I was able to play with things and play with new cutting patterns. I can look back on some of the first shorts I did, and now I look at them and think, oh, if I knew what I knew now, I could make this sing so much more! It'd be so much funnier! But you don't get to that point without having stumbled through shorts.

I think shorts are valuable, just purely even from a building your skillset standpoint, even if they don't mean a lot of extra money or you're going to Sundance with them. They have all been pretty invaluable to me in my path.

I think the best investment any editor can make for themselves is having their own system and their own editing software, whichever they prefer. Premiere or Avid or what have you. Finding the time to cut scenes and cut shorts and see how things play on a whole.

It may not be the best-looking thing you've everworked on, but you can also help elevate it. A quote-unquote “bad short” doesn't have to be a bad short.

You can make anything look good with some elbow grease.

I helped my sister out a couple of years ago. She directed her first short ever. She was a first-time director almost right out of college.

There were a lot of production problems, sound problems. It didn’t look like the best thing in the world, but we put together a pretty good short and it went on to the festival circuit. She’s been in a ton of festivals for it, which is not bad for a first-time director. So continue to value what you can bring to any kind of project.

Did you cut Weird in Avid, or was that Premiere?

Weird was Avid. Basically, every show or movie I've worked on has been in Avid, but I also do Premiere. I cut on the Always Sunny podcast as well in my spare time and any personal projects I do for myself. I kind of find myself wading into Premiere more just because it's helpful to have that one-stop shop for graphics and get and in and out. It's very convenient.

Once upon a time, I learned on Final Cut Pro 7, so there's a part of me that always knows that. I also learned Avid at a very young age. My heart belongs to Avid as well.

One of the clips that is on YouTube from Weird is the “Another One Rides the Bus” scene. This is a scene that is primarily just a song. What struck me is, it's funny, it's a song, and yet it tells a story.

This is the third musical number in our film officially. The first one is him coming up with the idea for “My Bologna” and that was Al's personal journey. Then, he does “I Love Rocky Road,” which is his first performance in front of people at a really rowdy bar. That story is about him trying to believe in himself and win over the most unlikely people.

Then, you have to elevate it for this third scene, which is him performing for the best of the best who don't believe in him. You have Wolfman Jack, played by Jack Black, who is goading him into coming up with a parody song right there on the spot at this pool party.

There's this kind of standoffish nature to this performance, so the things that need to be balanced is the physical performance of the song. I love cutting musical numbers. Everyone we worked on in this movie was an absolute dream. I love making a super multi-group for everything, where I group every single clip together in one thing.

For those who aren’t Avid editors, a multi-group is using multi-camera.

Yep. Even though they're not cameras that we're recording the same take, I take all the takes and I make an endpoint basically on the first note of the song and sync every performance to it so that I can watch all of them at once sometimes or at least toggle through my cameras.

At least for the first pass, what I like to do is I make the multi-group, bring it in, and then I watch each camera individually. If I see a specific moment, I like, I make a cut and bring it up to the next layer. I do that for every camera until I have a huge modgepodge of moments that I like. I say, “Okay, so now I need to fill in these gaps because there wasn't anything that stood out to me,” so now I have to hyper-focus on that.

I do the performance cut first and I just try to make the best version of Dan’s performance and the band behind him that I can. Once I had that, then it was about tracking the performance between him and Wolfman Jack, where you have Jack Black doing the best reactions in the world of disbelief into “What is this kid doing?” and continuing to goad Al.

Al is showing off in front of him, so I found moments to intersperse so that at any point in the song, you're not forgetting that that's the central conflict of the scene. You never wanna forget that Jack is watching this whole thing. That was the next pass I did.

Then, the third pass is all the cameos that are in it. Specifically, there was a scripted breakdown where at some point, each of the big cameos does a little solo of sorts on a children's musical instrument. We had so many options for those, so I went through and interspersed. Those all felt like they should go together because trying to integrate them earlier into the song, it felt out of place.

When it got to the solo, I'm thinking, this is when you can just start having fun and cutting to every single person like Salvador Dalí playing the fish with a violin bow. That was the third pass I did.

What was really interesting in putting that together is they did one take where you saw Dr. Demento handing out the musical instruments and trying to make some kind of continuity as to why they suddenly had these musical instruments. But I was thinking, it's so much more funny if you just suddenly cut to close-ups of people having these musical instruments. No one's gonna question it.

Absolutely. There's no need for that. That's great.

Yep. Then, when we got into the director's pass and the producing pass, not a lot of it changed. Eric was very focused on making sure the collapses were all right. That was something we really went through and made sure rhythmically everything was working because I was so focused on performance. I wasn't necessarily paying attention to continuity in the moment.

We did that and then Al had a very specific vision of what order the cameos went in. But because I had built a base that was pretty interchangeable — the strong performance was underneath and these things could be moved around as needed — I could pretty easily give out the order of cameos that he wanted to see.

That's pretty funny that there was an order that he cared about because I didn't really think about that. Once you see a cameo, you think, oh, that's cool, but you don't think that they need to go in an order.

I know. I didn't [laughs].

Let's talk about notes and your attitude towards them.

It’s okay to have attitude. For every pass of the notes, you're sharing it with whoever received the notes. So once we got studio notes, then it was me and Eric's turn to say, “This is bullshit! That's a stupid note! No, we're not doing that!”

It's important to have that mourning period, where you look at the notes and say, “Don't like this. Don't like this. No, I'm better,” but keep that to yourself. Don't externalize that to anyone that it matters to.

Like a podcast audience of thousands.

Exactly [laughs]. It's okay to have a moment to lick your wounds. I walk away, I come back, take a deep breath. I say, “Okay, well now we try them.”

Usually, they're right. There's definitely a sliding scale of how I feel about notes where some notes I didn't think would work work and that's great. Then, there's some notes where I think, I don't like this as much as I liked it before, but this is a performance preference and I'm not gonna fight anyone on that. If it works just as fine, then that's what it is. That's their choice.

Then, I save up as much cred as I can for whatever note I really desperately wanna fight for. Because if you're fighting every single note, then you're losing the trust of the people you're working with because they're just gonna think, this person's not listening to me, this person doesn't care what I think, they don't value what I think and this isn't a partnership.

You wanna like keep thatcollaboration going and keep that partnership. If 90% of the time you're doing that, then when you wanna fight for the notes that you really feel passionately about, they're gonna be more inclined to listen to you. That's what I think is like the most important part of that process.

How does that argument go when you do finally feel really passionate? Can you do that verbally or is it simply showing “here's this cut, here's this cut” and you're done? Or do you explain it?

It's both. I'll always do it. I never won't do the note unless it's literally impossible. I do hate when someone will say, “Can you do this?” and I say, “For reasons of blocking and the footage we have, no.” That's when I feel the most defeated because I believe in using all the tools we have, like split screens and anything else to just try to craft the performance. But on the rare occasion you can't, those are unfortunate times.

Other times, yes, I do every note and I will play them. Usually, I kind of play it and I'll sit in silence for a second and say, “What do you think?” If they're happy with it, like truly, truly happy with it, I shut my mouth and I won't fight in that situation.

But if they have a little bit of hesitation, I'll say, “So in this performance, I don't think we're getting the groundedness that we were looking for. This feels a little bit more broad and I think that's what you're reacting to.”

There was one big note we got from producers when they were just trying to trim down the movie. There was a time when they said, “The movie needs to be 90 minutes.”

We said, “Well, we understand on principle what you're saying, but we've gone through and we've trimmed everything that we can.” Someone threw out the very big “Why don't we just cut the entire Doors homage and we go right from the ending of ‘Like a Surgeon’ into the diner? You won't miss it. It'll be a great deleted scene we can show.”

I did it for Eric and we took it out and we looked at it long and hard and we thought, it doesn't make sense to lose this. This is a biopic and we need to show Al at his lowest. And right now, it is implying that he did this performance and now suddenly, he's at his lowest in the diner for no real reason. We need that moment to happen.

That was an example of having a partnership with your director. I feel like for the most part, you do all the notes and you work with them with your director, but you don't necessarily show every note to other people because if you believe that strongly in something that you don't wanna do it, it is best not to show it to the higher ups on the off chance they say, “No, this works great!”

It's better to say, “We tried. We don't think it works for X, Y, and Z.” Again, it's all about that mutual trust. The trust you have with the director, the trust the director has with his producers, where hopefully they will listen to him and say, “Okay, this is your project,” which they did.

This is your project and if you say that this works better with that, then we'll let the note go. That's kind of the process we go through.

What’s a favorite scene or a complicated, difficult scene that you can remember from what the difficulties were or what made a scene great?

I think my two highlights, one is the diner fight. The challenge with the diner fight was just in terms of we didn't have a lot of footage.

That was one of those nights in an 18-day shoot where they said, “Okay, now it's time to shoot the fight scene. We have 15 minutes before the Burbank police kick us out of this diner.” It literally became two cameras running, one or two takes of everything, and hopefully it works.

That's a challenge because you say, “Okay, so we don't have the tools of options, so we have to look within the options that we have and how do we make this still work and how do we make it so it doesn't look like a cutty, jumbly mess, where we're not tracking the action, we're not tracking where the choreography is going.”

That was a big thing. Shaving frames and using flash frames in order to make it seem like impacts were happening a lot harder than they may have when they were shooting it on a rush day.

What we were proud of with that is when it was done, the first note we got back from the producers Tango was like, “We did not think this scene was going to work when we were there that night. We thought we were gonna have to lose all of this. There was no way this was going to cut together. And look at you guys, you made it sing.” We said, “Great. That's a victory.”

I feel two points of pride. There's the pride of making something out of almost nothing and then there's the pride when you have so much footage and you are able to tell the best story you can with a wealth of options.

It's not a scene that is talked too much about, but that first half of the “My Bologna” montage when he's coming up with it, that was their first day of shooting. They got multiple angles on everyone. It was so much footage. I loved being able to bop around and tell more stories just from people's faces. When it was done, I thought this is a really good scene. I really love what we did with this scene.

Absolutely. Your peers obviously agreed because, again, congratulations on the ACE Eddie for this project.

Thank you so much. I share it with everyone who worked on it. I mentioned Peter, who did a wealth of cutting on it as well.

Who are some of the other people on the team that you'd like to mention?

Peter, fantastic. Our post producer Kelly. All the team at Formosa. There's a great group of guys who were our sound team at Formosa. Anthony Venturi, Mike Gallagher, and Tony Solis were our mixing team.

We kind of got this great little post group going. We all went up to TIFF together. We were at the Beyond Fest. They're such a talented group of sound artists and half of this movie is sound.

They were working on an even more abbreviated schedule than we were, so what they were able to pull off was truly incredible. Then, we had the smallest VFX team ever that also pulled together the LSD sequence, the crowds at the “Like a Surgeon” performance.

It was a passion project of a lot of different people, who gave a lot of their time and their spirit to make it happen. And we did.

You did. Thank you so much for being with me and telling us about this great project.

Of course! Thank you so much for having me.

.jpg)

.jpg)