Today on Art of the Cut, Chad Galster, ACE, discusses cutting the series Yellowstone. Our discussion also covers Taylor Sheridan spin-offs 1883 and 1923.

Chad cut the 2021 movie Those Who Wish Me Dead (also written and directed by Yellowstone creator Taylor Sheridan.) He’s also edited the features A Score to Settle and Beautiful Boy, and the TV series Mayor of Kingston, The Proposal, The Bachelor, and The Bachelorette. One of the things we’ll be discussing is his move from reality TV to scripted TV and film.

Chad Galster discusses editing Yellowstone 1883 and 1923

You've done a lot of projects with Taylor. How did that relationship begin?It began in the most random way that I could think of. How do you meet people? How do you start working with them? I was a reality editor for a very long time, and I was having a great career. I loved being a reality editor.

You were on The Bachelor and The Bachelorette.The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. I did The Hills before that.

When I came out of film school in the early 2000s, reality TV was having its huge moment. Those were the jobs that were available. I actually started out cutting documentary television for National Geographic, History Channel, and Discovery Channel.

I took any job that came my way. I thought, “I'm gonna learn something here. I'll meet people.” I worked nonstop while I was still a film student. I was starting to get work.

I had just found my way into these shows and they became legacy shows. They just kept going on and on and on. I was having a nice career and really enjoying myself and I loved the people that I worked with. I started to be a supervising producer, co-executive producer of post, and all that. I was doing great.

Then, a friend of mine — a reality editor who at the time I'd known for 12 or 13 years — we worked together on The Hills and The Bachelor, our careers just were kind of in lockstep. He had known Taylor Sheridan as a friend for 20 some odd years. They go back to when Taylor was a broke actor and my friend was a broke whatever he was doing before he became an editor. They were just friends. They had a relationship, a personal relationship, and lived together for a while. There were just a couple guys in L.A.

Yellowstone season one happened and they were cutting it. Taylor directed every episode of season one of Yellowstone and they needed some help. Taylor said to my friend, “Look, I'd like to meet the best reality editor that you know.”

He was very specific about it being a reality editor. Because what he had seen is that my friend, who was a reality editor, was the fastest editor he knew. He’d kind of throw things up against a wall and then try out a million things. He wasn't concerned about the script. Once you shoot it, the script goes away.

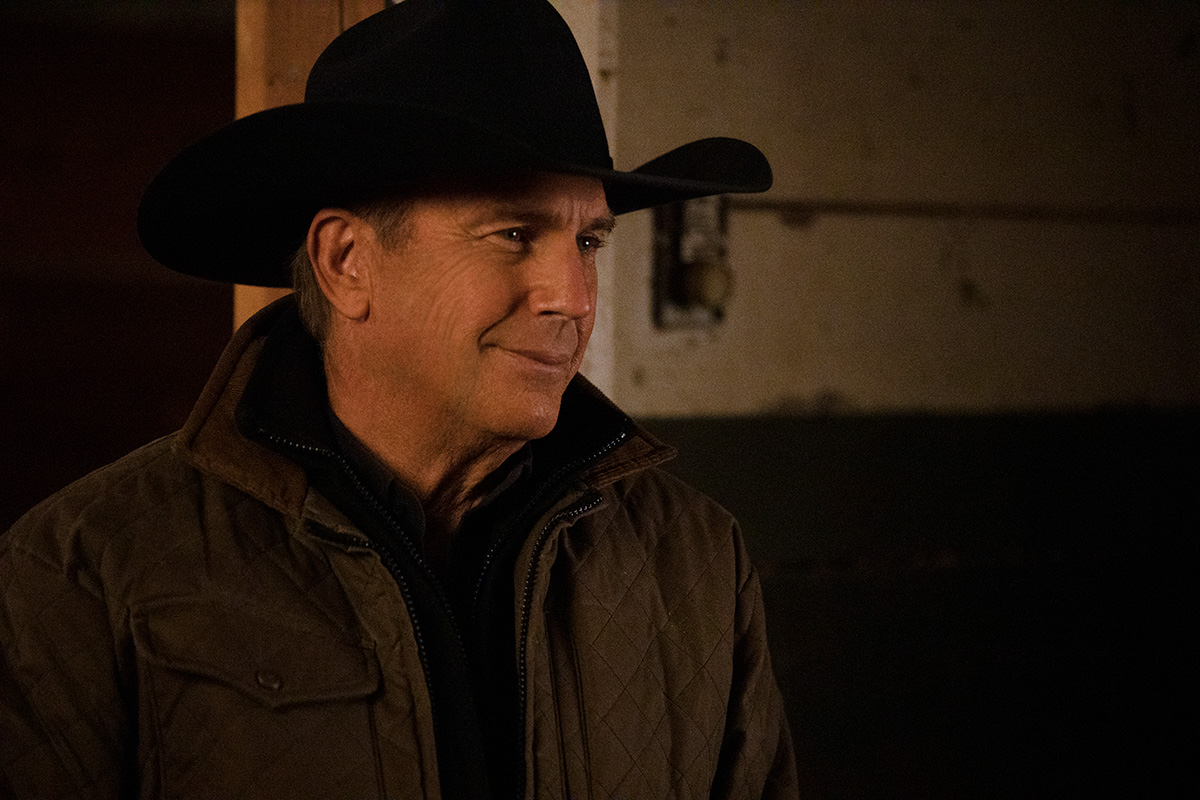

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Problem solver! I mean, that's just the nature of that kind of work. And so, he introduced me and I flew out to Park City, Utah, and they were shooting season one still. I flew out to the soundstages there and the Avids were attached to the sound stage complex in Park City at the time.

I cut a scene for Taylor, this kind of complicated, six or seven person dialogue scene, bunkhouse scene. I had a couple hours to do it and he came in. He was in between setups and he watched it. He says, “Alright.” Then, he went back out and kept directing.

He invited me to his house for dinner that night. He said, “We don't know each other, but I am impressed.” He was very sweet and he said, “You wanna see if this works out?” We have never looked back. I haven't worked for anybody else since.

That was season one. I've done all five seasons of Yellowstone, The Mayor of Kingstown, 1883, and now 1923. I did his Angelina Jolie movie that came out about a year ago. We just hit it off as people. At first, we hit it off as artists, because he just makes exactly the kind of stuff that I like. Turns out he makes the kind of stuff that a lot of people, which is cool.

True.But at the time, what I knew of him was Sicario, Hell or High Water, stuff that he had written. I had seen Wind River and I really liked that movie. To work together this successfully for this long, we realized pretty early on that we just enjoyed each other as people.

It's a coincidence of artistic taste and it's a coincidence of personality and it's a coincidence of my friend having known him and put us in the same room together. That's what separates a lot of very talented people in all walks of life from maybe a job that they would like to do. There is that initial coincidence. And then, we kind of took it from there as people.

Over the years, it's close. He and his wife and son treat me like a family member. I consider myself close to them. They know my family. You forge a relationship that begins something with work and then it becomes something greater and it continues to grow.

At this point now, I've done 50-some odd episodes of his various television series and a Warner Brothers movie for him. It all started off with just the fact that I was a reality editor. There is no way to predict how you are going to find yourself moving through your career.

I just was happily doing the best that I could, working really hard, and then, this was presented to me. Now, my life is very different now than it was five or six years ago, just ‘cause I work in a completely different part of the business. But that's how it started. Pretty random, right?

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

It's always something kind of random. AND it has to do with that idea — which gets bad rap — which is, “it's who you know.” You got this job, not because, “Oh, he's your dad,” or something like that, where he had to give you the job. It was that you randomly knew somebody that was his friend.

Right.

And you proved yourself. It's not like nepotism.No.

But it is truly who you knew.I think what the best thing that you can do for yourself in your career is no matter what type of show you're doing — you could be cutting corporate videos, wedding videos, reality TV, documentary, feature, scripted — it's best if you leave a trail of satisfied clients in your wake.

I was just doing the best that I could at the job that was in front of me all the time. I worked really, really hard. On whatever show I was on, I wanted the thing that was the hardest. I wanted the scene that just wasn't working, that was something that we didn't quite get this in production. I would say, “Well, let me try it. I wanna try it.” I went through my career just aggressively pursuing improvement.

The conversations that happen that lead to you getting a job somewhere are things you never know about. They're between two people in another state or whatever going on like, “Yeah, I know this guy. He's pretty good. He works hard.” You have already done the work to put yourself in that position to get the job. You don't realize that that's happening. All you can do is be relentless at improving yourself and doing the best work that you can all the time.

Interior of the airstream trailer that was rigged to be Chad's edit bay for location shoots. He also slept in it when they were on location. It was a cozy home away from home.

Interior of the airstream trailer that was rigged to be Chad's edit bay for location shoots. He also slept in it when they were on location. It was a cozy home away from home.

And then, if and when something comes up, you'll be the name that someone thinks of. That's what happened to me. I wasn't doing it for that reason. I was just doing it ‘cause I really loved my job. I still love my job. But I loved my job when I was a reality editor too. I really did.

It's really hard. It's a lot harder than scripted from a story standpoint. I think every editor should have to do a reality show and/or a documentary just to understand what goes into putting those kinds of stories together.

I just instinctually worked on solving story problems and crafting stories every possible way that you could do it. A valuable, valuable experience. I didn't go looking for this relationship. I wasn't seeking it out. I didn't meet someone at a party. I just was someone whose name was on the tip of someone's tongue at the right time. I took it from there.

Like I said, Taylor and I, if we didn't like each other as people and if we didn't see eye-to-eye as artists, we wouldn't still be working together. But we do. I hope it continues for a long, long time.

As you pointed out, even though you knew somebody, you still have to have the reputation that they want to put their reputation on the line by introducing you.Yeah. You can know someone in the wrong way: “Oh, don't ever hire this guy. Oh man, he's terrible. Or not even terrible. He is just miserable to work with.”

On the occasions when I go talk to film students or what have you, I tell them that your personality — especially when you're starting out — your personality has so much more to do with your success than your skillset, because if you are a hard worker and you're the kind of person that people want to have in their orbit, they will teach you the stuff that you don't know because they'll want you to know it so that they can keep moving you up and keep working with you.

So, just work hard and pursue knowledge. Pursue the things that you don't know. Get in a little bit over your head from time to time. It's good for you. That's the only way that you grow. I've done it. I've looked around a couple times in my career. I’d say, “Man, I'm not sure. I don't know if I can do this.” And then you sink or swim, right? You just have to find a way forward.

More than knowing how to use an Avid or more than having encyclopedic knowledge of the history of film and television, “Can you tell a story and are you someone that the people enjoy spending 10 hours a day in a room with?”

Chad on the setat the Fort Worth Stockyards

Do I wanna hang with you?

Chad on the setat the Fort Worth Stockyards

Do I wanna hang with you?

Oh God, yeah. That’s it exactly.

Let's talk a little bit about editing. I've got a specific thing that you might not remember cutting, but hopefully the overall idea we can talk about. Season four of Yellowstone, episode one has —I do remember.

— a bunch of jump cuts and mayhem before the credit sequence. It's crazy. Talk to me about the usefulness of jump cuts and choosing not to cut in continuity.Yeah. Couple things. Yellowstone overall has a very classical style in the way that it's shot actually, if you think about it.

What jump cuts help you to do is to keep people on their toes. They allow you to cut from energy to energy to energy to energy instead of geography to geography to geography, right?

Because what's exciting, what keeps people engaged in the story, is the emotion of it and being swept up in that. When you're jump cutting, especially if something is maybe an action sequence or what have you, then you're just exposing them to the most exciting, dramatic, scary, horrifying moments in a sequence back to back to back.

They stop experiencing your story as a thing that has to make sense for a moment. They're just experiencing an emotion. I think to me,

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Jump cuts are the easiest way to get inside a character's memory because we don't remember things in a linear fashion.

Think about some of the things that were most important to you in your life. I think about the day that my daughter was born. I remember snapshots of the hospital and the delivery room and all of that. I remember feeling the things that you feel when you have a child, which is the most incredible moment of my life, but I remember them in pieces.

Certainly — especially when you're dealing with how a character might have perceived a scene emotionally — jump cuts can be very effective ‘cause you're just flashing through it the way that it would flash through their mind in memory, if that makes sense.

Taylor actually talks about this a lot. At some point, geography stops mattering if you're telling an effective emotional story. I'm very meticulous about — in an action sequence — people feeling they know where their place is: that the audience knows where they’re placed inside the action sequence.

But after a time, if you've got them, then they just want to ride this emotional wave with you. You can break down, you can put away the geography for a second and just start moving them through the story and experiencing something visceral that just makes them feel, and they just forget about the story for a second.

You say these things are all kind of theoretical. I don't know if people actually have that experience, but that's what the goal is. Ultimately, the goal is they don't think about any of it. They just say, “Oh my God! That was incredible!”

That first act of episode one of season four of Yellowstone was just one of the most fun sequence that I've ever cut together. It was just wild. You put your foot on the gas. We don't stop. It's 13 minutes of mayhem and then the credits hit. Welcome to season four. That was lot of fun to do.

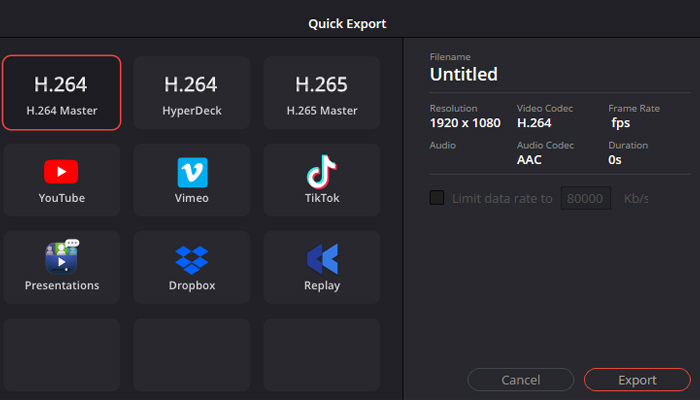

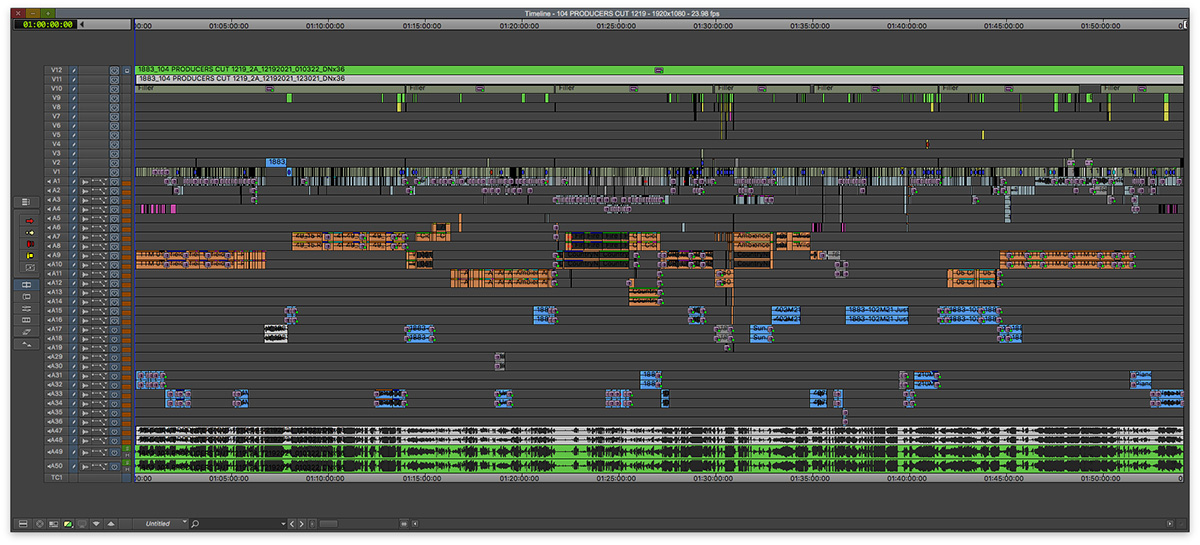

Yellowstone, Timeline for Yellowstone #401 - Half The Money

Yellowstone, Timeline for Yellowstone #401 - Half The Money

You have to always be thinking about dynamics. Visual dynamics and audio dynamics. Not even just levels, just in pace.

My background is that for the first half of my life, I was a classical musician. I was in the band and I followed it through like college years.

Music is just something that I am always thinking about. Music dynamics are incredibly important. The loud is only loud if you've had something soft before it. A lot of editors talk about this, but I think it comes very, very naturally to me to always be looking for the moment where you can have something explode and then just settle and then there's nothing.

You have to think about it or feel it or it rings out not only in your ears, but in your chest, in your mind, as you think about what you've just seen. If all you do is have just action, action, action, action, action, that gets exhausting.

Similarly, if all you do is just slow, contemplative, people looking at each other, that gets exhausting as well ‘cause you're trying to find a way to connect to what's happening. It's something that you only find out really when you've usually cut all the little scenes.

You cut all the scenes together — they were shot out of order — and you watch the whole thing for the first time and say, “Okay, is it a rollercoaster ride or is it just a long slog up the hill or a long, slow descent?”

If it is one of those latter two things, you have to find a way to change that up so that your audience remains engaged. Editors are all different. I spend a ton of time on sound design in my offline edits and we have excellent sound teams that then take that and they'll use different effects or what have you.

But I leave a very specific roadmap in the audio track as to what I think should happen. It might be that all sound goes away in a violent action scene and we hear nothing. We hear little pin-drop moments from various sound elements on screen.

I spend a lot of time with that and it's all towards what you're saying, which is that the dynamics are gonna need to keep my audience engaged with me. I wanna make sure that I don't lose them. If we've got a long dialogue scene, then what comes next?

We've gotta maybe elevate the pace and the sound design, the visual design. It's just constant. It's like breathing. It's not even a thing that I think about. I don't think I'm unique in that sense, but it's a powerful tool.

Taylor is aware of that as well. In a good script, it will be written so that something exciting happens and then something violent and then maybe you'll take a pause or you'll pull back and then you try to go back and forth that way.

But on a page, it's different. You might have a good roadmap, but when you put it all together, you think, “Ah, we've got a little too much dead space here. Can we take this sequence and move it? Can we split up these two quieter parts with something big and exciting?” That's part of just crafting the episode after you've put it together.

It's the main way that you keep people interested. You've gotta keep changing things up. When you have characters that people are interested in, they will watch them do something quiet for a long time.

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

I remember there was something, it was season one or two of Yellowstone and it was Kevin Costner in a horse stall. He was having a dialogue with some character and then the character walked out. Then, Kevin just kind of sat there and then he walked over to the window, the horse stall, and started looking out. Even in the daily footage, he's just fascinating.

I put it in the cut. Taylor said, “That's why you hire Academy Award-winning actors.” I said, “You didn't tell him do that?” He said, “No, I didn't tell him to do that. He just did it.” Just watching him do nothing was fascinating.

There are people that I've had the good fortune of cutting, working on Taylor's shows. Sam Elliott just is fascinating as a face and a person and a personality. You could just watch them do nothing and there's always something happening in their face.

What that depends on is an actor who's embodying a character to an uncommon degree, to the kind of thing that you get when you work with those kind of folks. Hopefully a situation and a script that supports it, that you are emotionally invested in.

Again, if you are emotionally invested in something, you will watch silence for a long time. Just watching people feel. That's not something that always works, but it can.

When we have a scene where it's just characters in the aftermath of something or quiet dialogue exchange, I am very comfortable to let it just sit on one person's face and just watch them and just watch what they're bringing to that character and not cut away from it at all.

So there are times we'll have 10, 15-second shots in dialogue sequences, just ‘cause what they're doing is so interesting. Absolutely as important as the quick-cutting action stuff is to just know when it's time to rest and sit and watch and —

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

A hundred percent. They start putting in: “What have we seen so far? What does this mean? I can tell what he's thinking or I can tell what she's thinking.” It gives them time to advance the story in their mind. Where are we? Alright, we're gonna rest. What have we been watching? What are we feeling right now?

It goes back to the dynamics discussion, but also a writing and a performance thing. Because, for lack of a better word, just letting people be the character for a bit and not getting in their way.

A lot of people have talked to me about editors having styles, which I don't think is true. I think most editors that I've talked to have said, “You better not have a style.”Better not, yeah.

I was thinking about that with you in particular with Yellowstone and 1883 because I was kind of watching them simultaneously and they are paced very differently. Let’s talk about the difference between one project and another. Is that something you're finding just from how the dailies are speaking to you to cut with that pace of 1883, or is it something else?The dailies always will tell you what the pace is. I think, first of all, you're right. An editor should not have their own style. If you think that you have a style, then you're limiting yourself and placing yourself in front of the story or in front of the show.

Movies have styles. Directors have styles. You can think of five directors off the top of your head, like, “Oh, that's a Guy Richie thing. That's a Quentin Tarantino thing.” But the dailies should always be what tells you how to cut it. If you don't mind getting to methodology for a second…

1923, Paramount+

1923, Paramount+

Let's say a scene has five or six setups and there are three, four cameras each. On 1923, we actually have five just because of the scheduling, which is a lot.

If there's a setup that had five takes, I'll start at take five and I'll watch that first, because take five is where they think they got it, right? Usually, the actors and the DP and then director and all the people say, “All right, we got it moving on.”

I will then watch take four. Take four and five are usually the most important because a lot of times, they’ll think, we got it on take four, let's do another one, see what happens.

Those two takes are really, really important but then you also have to watch three, two, and one, and actually do it in that order because you will find sometimes — especially when you're working with really exceptional actors — they will come in having thought about something and they will have their performance figured out on take one and you better be ready to see that and you better not overlook it.

If Harrison Ford is coming in to do a scene, he's thought about it. Helen Mirren, they've thought about it. Sometimes, on take one, you just get this magic from these professionals, these artists, who are just ready and who are already embodying that character.

I think for actors that are less experienced, they'll kind of ramp into it. Three, four and five are really important takes for them. You'll also find — I mean, this is just a reality — when you have big movie stars like that and then you have people acting in scenes against them, they're nervous sometimes. You can hear their heartbeat thumping through their lav on take one.

1923, Paramount+

1923, Paramount+

Just hammering, hammering away.

What am I hearing? What’s that sound?Yeah, that's someone's racing heartbeat. Make sure we have the medic on standby. Takes 2, 3, 4. Their heartbeat will kind of settle down and then they just start doing it.

I start at the end and then I move towards the beginning and make sure that I'm not missing anything that a performer gave that should be in the show. You do that over the course of a scene and the way that I put it together is, for each beat and sometimes each line of dialogue, I'll just build what we used to call a KEM roll.

You've just got this maybe 45-minute sequence. Someone says I love you six times in a row and then you see them back-to-back and it becomes quite clear which one is the best for the scene that you're cutting.

I always make a duplicate of that sequence, so if I ever lose myself putting a scene together, I can just go back and watch the 45-minute KEM roll of what I thought were the best or just all of the moments put back-to-back and I'll compare them.

Let’s say someone says “I love you” and we see them do it six times. Maybe take three is my favorite, so that one goes in front. Then, any others, I say, “Are you beating that one? Yes. You go in front now in my sequence, or if not, no, you're pretty good. You go on the other side of this one” and then just have this long string out of material that I can always go back to and watch if I've gone down a path that I don't like. “All right, where did we all start? What did everybody give me?” You just watch it again and let it wash over you and get back to it. So I just go through that way.

For me, what I call a “KEM roll” is every setup with every take laid back to back to back for its entirety. Once again, everybody's terminology is different. Then, for me a “line-reading reel” is where you’re seeing every take and set-up of “I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you” back-to-back. I do them both. I'll start with a KEM roll and then start breaking it down into a selects roll or a line-reading roll. You keep ‘em both. Even if you cut it right, even if maybe Taylor comes in and he says, “I think she's too hot on that reading. Do we have less energy or more energy?” Then you can go back to that select and say, “Yeah, we do. Here's one.”Exactly right. I don't really have the patience to do all that many intermediate steps. I go from the 45 minute to the two minute pretty quickly or whatever the scene requires. But along the way, I will save and duplicate and say, “All right, I might be doing something here that won't work, so I'm gonna duplicate where I am right now, make a new sequence, and then go to town.”

The freedom of doing that is that I could try anything. I can always go back in time to where I felt I've got what I think is the best stuff and then back further to where I've got everything, and you can step forward and backward as you work through a scene.

That's a method that a lot of editors have landed on and I didn't even realize it until I heard it on your podcast. I don't remember who it was. Someone talking about it and I thought, “Oh, I do that. I bet a lot of editors do that.” It's just a way to let everything kind of wash over you. I also don't have the patience to just watch dailies. I've never had it. I have to be doing something immediately with them. I have to either be putting them into this KEM roll or selects or whatever and I need to be working on it right away.

I can't just sit there and watch. When I think about what folks used to do and they would just string up the reels at night after the end of a shoot day and watch dailies for three hours. I can't imagine anything more painful.

It's another place where editors are very different. There are people who say when you watch dailies, it should be a completely passive exercise. Then, there are multiple people that say, “No. You’ve got to be active right from the beginning. Otherwise, you're just wasting time.” Especially with TV schedules! You just do not have that time.The timelines on these shows that we're doing tend to be absurd, but I think that your gut instinct and your first reaction to something is really, really valuable and you don't get that back. You only get to do it once.

What was in the moment? What struck you about a performance or a line reading or a shot? I want to grab that right then and there and just say, “This was important to me. This felt right” and put that into a timeline. Then again, start ranking the other ones and going before or placing shots before or after that one based on how much I like that take.

But your audience only sees it once. I mean, if they love a movie, they'll watch it 50 times, but they're just letting it wash over them.

I think that everyone can have their own method and that's fine. I understand the logic of passively watching dailies, but I just start reacting to it right away as a viewer. I want to be able to start making decisions and making notes to myself in that first viewing. Your first impression of a sequence, a take, a shot, is so important and I don't wanna lose that.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

You gotta have good writing first and you gotta have good performances. Let's take it for granted that we have those two things.

I think withholding information for as long as possible is really uncomfortable. It makes people really uncomfortable. I'm trying to think of an example from something that I've done. I think Taylor's work is rather rich with that kind of situation, but it's the unknown and the unseen that makes people uncomfortable and makes them tense.

Let's say that there was a shot of me and I'm holding a gun against some other character and I shoot and you don't cut away from me. What happened? Did you hit him? Is he dead? Alive? What's happening? Did he run away?

The not knowing is such a fun tool to have. Just keep holding on until that last second and then you release. “Oh, there's what happened! Oh my gosh. Well, what next?” Well, I'm not gonna tell you just yet.

There are a million ways to do that. One is just quite literally the pace at which you cut things, how long you hold on a shot. Also, you could do it with audio.

I feel like this is a clunky example, but let's just keep using it. The gunshot, then you hear a scream, then nothing, then maybe some footsteps or some rustling.

The audio, the sound effects, are giving you additional pieces of information that are saying what's happening next in the story, even if you don't have the visual information. Holding it back and not releasing it until that absolute last possible second is a guiding principle in creating tension, I think.

You won't find anyone who's more interested — and I think probably, hopefully aware —of what the effect music has on a cut than me, just ‘cause it's part of my soul, my life.

Knowing when not to use music is so powerful that it becomes the graduate-school-level of working with music. That's when you don't even see the code anymore in the Matrix. I don't need it here because you have the confidence to say that the story's doing all the work for me.

Let's say you and I are sitting in a scene together and the audience knows we don't like each other. I can put in a piece of music to tell them that or I could just let our looks tell the audience that.

The silence, the uncomfortable silence of something, the sounds and the environment, little things that you hear. Yes, music can create tension, but silence can also create so much tension.

Sometimes in moments of greatest tension in Yellowstone or certainly in 1923 — there's a sequence right now that I'm thinking of — taking the music away and forcing the audience to just watch something that is unpleasant or that they don't want to happen to a character and not commenting on it musically is actually so much more powerful.

1923, Paramount+

1923, Paramount+

Mm-hmm. Or you'll start to hear a riser or something and think, “Oh, the killer's about to come. Or something is gonna come from off-screen and I know it because I'm hearing it ‘cause you're telling me.” It's all a part of withholding information. You're withholding the information that the score would give you.

The score would tell you right now, “Okay, be happy. Be sad. Be afraid.” Or again — like you said — in the absence of that, “I don't know what to feel. Holy crap, I think I'm happy or I'm sad or I'm afraid” or what have you. The audience member is along for the ride in doing that work themselves.

I use music plenty. We do in all the shows and I think it's very effective, but I'll usually wait until after the moment of decision for an audience as to how they're feeling about something, if that makes sense. The scene has resolved itself and then we’ll comment on what you've seen or will use it to transition to a new scene.

But I think if you're doing it correctly, you don't use it to give the audience the answer to a scene. Make them work, watch, engage, and be involved and make their own decisions and find their own answers for a scene. You can comment on it afterwards. Hopefully, you haven't spoiled whatever conclusion the audience member came to.

Really, really potent tool, but you gotta be so careful with it. Same thing with a love story. It's a crutch. “Oh, these two people are falling in love” and then we're gonna tell you, and then it doesn't feel as earned as if you say, “I don't know, are they falling in love? Do I believe what I'm seeing?”

And if you do — if you believe it — and the writing is good and the performances are good, then the payoff is so much greater, I think, if you haven't layered any tricks in there, if you just let the writing and the actors do the work.

We've got all the tricks. We can use 'em if we have to, but ideally, you just wanna watch two people connect and just experience that and experience it without anything else around it.

I'm just sort of aware of that. Aware of: “Yeah, we could do a million things to make it very obvious what the answer should be to a scene.” Or we could let you figure it out and then tell you maybe, “Alright, yeah, we kind of think that too. Here's the music.”

Something you pointed out about using music as more of a transition. For example, after the scene has told you what it is, then the music comes in. I think if people watch film and TV, they'll see that some of the best use of music is more transitional than it is from the beginning to the end.Yep. If you're just wallpapering your show with music, then it's like anything else. It just becomes this din or it becomes the action movie that we talked about. It's just all gunfire and explosions and then you're just numb to it after a while.

If you have what we call wall-to-wall music — there's a lot of shows that do that — then the individual pieces of it stop meaning anything.

My most common mixed note would be, “Hey, let's delay the start of this music cue three or four seconds, five seconds, whatever it is, 10 seconds. Let's wait until after this line here.” Delaying is the most common note. The music that happens over a transition allows for a reflection or it's a palette cleanser.

It's the sorbet before the next scene. It just allows you to reset yourself and be prepared for what comes next.

Using it as a transitional element is how we most commonly use music in Taylor’s shows. Again, we're not unique in that regard. There are obvious exceptions when there's an action scene that's gonna be scored, usually most of the time, but sometimes not.

One of the best action sequences I think probably most of us has ever seen is in Heat, the shootout downtown. There's no music in that and it's mesmerizing and captivating and horrifying and and scary. We modeled the shootout in episode one of season four of Yellowstone after that sequence, the one that you brought up earlier.

There's music, action, car crashes, then the shootout happens, and then there's nothing. Took it all away. It's just gunfire and you just feel so very much in that scene as an audience member. Just stripping away the movie artifice of it and say, “Oh my God! This is terrifying!”

That scene was an homage to Heat. I don't think Taylor would mind me saying that. I think he has said that. That’s a scene without music that is captivating and exciting and engaging as a scene as you could think of.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

In a very polarizing way, apparently.

Talk to me about pacing that and getting in and out of it, and choosing it.1883 was a really interesting project in so many different ways, but one of the main ones was that voiceover. God, polarizing is probably putting it lightly. They're people that really love the voiceover element of that show, and there's people that hate it like really hate it.

** SPOILER ALERT **

1883 is a show that really asks you to watch all 10 episodes before you make a decision about what we've done with some of these various elements. What you realize — and I mean, spoiler alert of course — but that character has been dead the entire time. The character of Elsa in 1883 is speaking to you from beyond the grave from the beginning.

In fact, she tells you that in her opening sequence. She says, “If this is hell, then I'm a demon too and I'm already dead.” Then, we roll the main titles. That's in the first three minutes of episode one of 1883. It's there if you want it.

** END SPOILER ALERT **

So how do you pace that? You listen to the cadence of the actor. This is sort of like pacing anything else. You just treat it like any scene. What is the cadence in which she's speaking? Is she describing something that was exciting for her?

She narrates her love story. She has two love stories in that show, actually. What is the pace at which it makes the most sense to hear those things? It's another dialogue element really.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

We recorded it several times, three or four times. All of the voiceover for 1833 with Isabel was recorded. The first one was before we had shot a frame. She recorded the entire thing.

Then, we recorded it about a third to halfway through production and things change because now, Isabel May, the brilliantly talented actress who was that character, had been through some things.

She had lived this character, like really lived it for a while, so she felt differently. As she, the actor, is giving this voiceover dialogue, I can only imagine that she was placing herself in the scenes that we had shot, thinking about what she felt as she was shooting them, being the character.

** SPOILER ALERT **

Then, we recorded it all again once we were completely done with production. I was actually there for that one. There were some really wonderfully exciting differences. The weariness of the journey is what we were trying to get with that voiceover. We weren't telling the audience that she was dead.

In fact, you don't really know until the last episode. I think she says her last line of episode nine, when she's describing how her father looked at her and she’s saying, “That's when I knew I was going to die.” That’s the last line of episode nine.

** END SPOILER ALERT **

I know there are at least three complete readings of the voiceover. There are pieces of all of them in the show, and in the beginning, she is this bright-eyed, optimistic girl who's on a train moving to the rest of her life, very excited about what the future holds. She's a world-weary warrior by the end of the story and she just played those things very, very differently.

I wanna say, the very last line of the show or the voiceover, was from that third take. I remember just hearing it and she just said it in a way that I had never heard before. I looked at Taylor and we just kind of nodded to each other and that was it.

She was interested in exploring that voiceover and in doing it all those times and I think she understood the exercise of what it would sound like before she'd shot during and then after. Then, we just went through and what sounded the most truthful for the scene, from which performance.

It was a lot of fun. The whole show was really fun to craft for that reason. We're kind of playing this trick. We opened the entire series with a sequence from episode nine, so we're kind of balancing what we tell the audience and what they're starting to believe about the character.

Voiceover was a big part of it. I think voiceover had its moment in the history of film and television and then it kind of became vilified for a while. It is just only thought of as a crutch and I understand that ‘cause it certainly can be a crutch. It's very much passe.

I think now to use voiceover, this story required it because of the story that we were telling, how we were telling it, and the perspective of the character. We needed her to have the perspective of being beyond the grave to tell the story properly. It was just a thing. It was part of it from day one.

We start the show with it and people would say, “Oh no! We don't like voiceover anymore. This isn't right.” I think that folks who watched the series all the way through understood it. What I've heard from people is, “Yeah, I didn't like it at the beginning, but then I understood it and by the end, she made me weep when the last shot rolls.”

I cried every time I watched that damn show. It's very emotionally affecting.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

I was just about to say, it's sort of like a book. You get all the wonderful things about being inside someone's head that you get from a book. Again, it's just the way that Taylor crafted this story. You needed that. You needed to be inside of her head to properly experience the story that he was telling.

You needed her emotional perspective. A couple times her plot perspective, but really is just all about emotional perspective. She just becomes this weathered veteran. Like I said: “warrior.” That journey was in 10 episodes of television. I don't think it would've been as rewarding if you didn't get to go along that trip with her in her mind and have her talk to you about some of the things that she was feeling and experiencing.

The giddiness of love and young love and then the absolute devastation of loss of that love and what that feels like. Isabel is a generationally talented actress, in my opinion, so if you're ever gonna do it, it's with someone like her. She was exceptional. But I think it just added this layer that made that story so much more emotionally engaging to hear from her.

There's people that disagree with me and that's fine. Everyone gets to have their opinion about it, but that's what we did. 1923 has released, and so now, people have heard that we are doing it again. It's to a lesser degree, but it's just part of the story and I think it helps.

I love the idea that somebody once told me about criticism from audiences or notes — not notes from a director, but maybe a studio: “A lot of times they're not giving notes on the same movie you’re making.” If somebody says they don't like the voiceover, that's THEIR version of this movie. Our version of the movie has voiceover.It's so true.

Notes are a whole thing. How you deal with notes is such a big part of this job. If you can't take a note, you don't get to be an editor. That's just the reality of it. Or you don't get to do it for very long.

But what you're saying is you have to understand, or at least be willing to look at, where the note is coming from.

People aren't always trying to make the same movie that you are. Let's say that I was sitting in a notes session. Let's say I'd cut The Avengers or something and I get this note that says, “This is good, but there's just too many damn superheroes in it.” They're not trying to make the best Marvel movie that we can make. They're making some other movie that they have in their head that has some of the same thematic elements or what have you.

Notes are valuable. I give notes. I try to put myself in that place as well. I think, “Well, okay, I don't really identify with this story, I'm not engaged, but I wanna help you make the best version of it that you can make. Trying to understand what you're trying to do, here's what I think would help you bring forward the best version of this thing that you are trying to make, even if it doesn't appeal to me directly.”

We are in the business of making entertainment for people, so an audience just gets to like it or not and that's fine. Not everyone's gonna like it. People will apologize: “I saw that, I didn't really like it, I'm sorry.” I say, “You don't have to apologize. You're a person. There's 7 billion of us. We're all gonna have different feelings about this stuff that we watch.” I don't take that personally. Thankfully, there's a lot of fans of the stuff that we do, Yellowstone and the various shows that we do.

There's a lot of people that don't like 'em. That's fine. That's the way it's supposed to be. If everybody liked it, that would just be boring. I enjoy the discussions that shows bring about.

Some of the most interesting discussions I have with friends are on movies that we just aggressively disagree about and trying to understand why a person feels a certain way about something.

It just tells you something about people. When you're an editor, you get notes from a lot of people. You get them from a director, sometimes the writer, if they have a producing position as well on the show. You get them from the studio or the network.

My feeling about them is that unless you wrote the show, or unless you came up with the idea for the concept and you hired the writer to write the show.

There have been people who have been thinking about this show longer than you have, no matter what. It's true for every editor. Those people deserve to have their ideas tried and they deserve to have them tried to the best of your professional abilities. I feel that very strongly. I feel that responsibility in my job.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

I may disagree. I often disagree. I have an ego just like every other editor, but they deserve my best effort at trying their note and seeing if it works.

Or at least showing them, “You know what? I know that this is what you had in mind. It doesn't work. Here's why. Here's the evidence. I'll show it to you. I took some time. I did my best version of it. It doesn't work.” Then, they could say, “Okay, I see that. Let's move on.” Or they'll say, “No.” Sometimes, they'll want to push further with it and then you go through that.

But the other thing to remember about notes is that some of the worst notes lead to accidental, beautiful discoveries because you're doing a note and you might hate it, but it forces you to go back and watch your footage again. “Oh, I missed this the first time.” Or, “Oh, now that I've put the movie together, this performance means something different to me.”

Because I'm going through my dailies again, just kind of going back to square one to see what's there, I'm finding that. And I may not have found that if I hadn't been doing this crappy note that I hate.

It's all valuable. You gotta be careful as an editor. There's this kind of perception we kind of get in online forums and you see this thing about everybody else is stupid and only editors are smart. That's just not true. I know some brilliantly intelligent producers, executives, and what have you. We have different jobs and we come at the material differently, but it doesn't mean they're stupid.

Some of them are because there are stupid people everywhere, but some of them are really, really smart. A defense mechanism, I think, amongst editors is to say, “Oh, that note is dumb” and it's because you don't wanna think that you maybe missed a performance the first time around or missed a beat that you could have used the first time around.

The faster you can get over that — the more you become a collaborative artist that is willing to find new things — the most deadly thing you can do on a long-running series is to become too pleased with yourself and to feel like “I've got this figured out.”

You have to always be looking for something different, a new way to tell a story, a new way to tell a scene. It might be like, in Yellowstone, there's a lot of horses, there's a lot of stuff that we do and a lot of ranch stuff. Alright, I've got this scene. It kind of feels like something I might have cut a couple seasons ago, but how do I make it different?

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

Yellowstone, Paramount Network

What is a way that I can do this to where it feels unique, it feels fresh to me first? Because I'm the first audience. And to keep not become too satisfied with myself, thinking, “Oh man, Yellowstone, I got that nailed, man, I can cut that in my sleep.” I could. It would start to be really bad and boring at some point because if you're not trying to discover new things and constantly challenge yourself, then you will start making something that feels stale.

Tying it back to the notes, I think that the notes that you get from people can help you be one of the things that help you not be stale, not be too pleased with yourself, not to feel that you've got everything figured out, and to be willing to accept to hear that and to accept it into your workflow that you may not have everything figured out.

I think it's important. The best editors that I know are people that are constantly looking to improve and not to feel that they've got it figured out, not the people that are trying to shut out any critique or criticism.

My feeling is “Bring it on. If I disagree with you, I will tell you, but I'm also happy to have the discussion and I'm happy to do the work that goes into deciding whether or not I agree with you or not.” I think it's really important if you want to have a long career. I can't overstate the importance of that actually.

I've told this story a couple of times about how I cut out a bunch of lines from a scene in a script without the director's permission, just ‘cause I thought they needed to go. The director was quite upset about it, and we put ‘em back in. By the end of a year of cutting the film, all those lines that I originally had cut had been cut back out again. I was right. But that is the wrong thing to take from that story. The right thing to take from the story is that the director needed to see his vision and to be able to see, “Oh, you're right, it doesn't work.” But there's no way he can own that if he can't see it his way. He's gotta see if with those lines. He's gotta see it the way he needs to see it and you can't just tell somebody “That's not gonna work.” Even if it truly doesn't, you just can't tell it.A hundred percent true. It's common to call the first cut of a movie or a TV show the editor's cut. I've never called it that. I call it a script cut. I'm not trying to absolve myself. You gotta see all the lines.

By and large, if you have the time and the luxury of doing it — and most of the time you do — you've gotta put the whole thing together. Just let everybody see it. My first cut of Those Who Wish Me Dead was 2 hours and 40 minutes long. It's a 94 minute movie. The version we released is 94 minutes.

You've just gotta go through that process. You just gotta put it all out there. Sometimes, if I feel strongly that even on my first go-through of something that some lines have to go, I'll cut that version. I'll just have it. After you've shown the version that has everything, you say, “This is what I think about this scene. I think we could do it without this, that, and the other.”

But then also, you can be blinded as an editor a bit by your own feeling that you've got a slicker way to put something together and you'll miss, “Well, yeah, it's cleaner visually if I cut these two lines out, but actually I am forgetting this thing that happens in act three where these two lines are important. That's kind of a clunky example, but —

— but you need a little lead-in. You need a pad. Maybe those lines aren't important. The audience is even thinking about ‘em because they're thinking about the previous scene or something.Yeah. There's all sorts of reasons why you can be “right or wrong” about lifting lines or what have you. Going back to the notes thing, at some point, these people that have been working on this story, this movie, TV show, have been thinking about it for a long, long time and they had a roadmap and they just wanna see if the map works, the map being the script.

Once you've seen it and digest it — and you usually have to watch it a few times — then you start being less precious about it. That happens for everybody. It happens for the director, producers. You start letting go of what you wanted something to be.

Once you've shot a movie, the script is useless, in my opinion. Going back to methodology a little bit, before I cut any scene of anything, I read that scene again on the page just to put it back in my head as to what little clues that you'll find in the writing of it.

I wanna make sure that I've at least seen all those things and I'm looking for them when I'm going through the dailies. Once it's all shot, you never look at it again. You never look at the script again. At least I don’t. I just say, “Here's what we got. We have this, that, and the other, and these things are resonating properly. This one, that was maybe written in doesn't, so that goes away.”

Some of it goes back to the reality editor thing. From what I have seen, editors I have worked with, I tend to be less concerned about throwing away scripts as some other folks are. I think you can get it ingrained in you. You say, “This isn't the script. It has to be that way.” And you say, “Well, what does that mean? It doesn't work.”

One of the tricks or one of the benefits of having had that background is, the roadmap, our script, tells us that if we watch this scene and we watch this scene, then we're supposed to feel this way about these two characters. What if you don't? Then you gotta start working. Then you gotta start figuring something out. You've gotta repurpose dialogue in a way that wasn't intended or shots in a way that they weren't intended. Putting together sequences in a way that they were not intended. You have to stop thinking about what the plan was and just look about what the result is and making something that connects.

God, that couldn't have been more true than on Those Who Wish Me Dead. There was a lot of that. There was a lot of, “Okay, this is what we have. How are we gonna make the most exciting version of this story?” I think it's more common in feature films just ‘cause you tend to have so much more material and you spend so much more time cutting something than you do with an episode of television. Mostly.

You just don't have the luxury of time in TV. Not the way we do it, at least. We started shooting 1923 in August and it was on the air in December. Same thing with 1883 last year. It's an absurdly short amount of time for the scale of production that we have.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

No, not at all. That's one of my favorite sequences, one of my favorite episodes of 1883 is that episode. Episode four. I guess to me, it also goes back to memory, to when we were talking about memory.

Shea, Sam Elliott's character, is having a nightmare about his experiences in the war. What are the things that would still stick out to him in that dream? What would he hear? He might hear this one gunshot. He might see lips move, but not remember what people said. You either hear nothing or you hear this garbled kind of mess of sound and dialogue.

Then, there's gunfire and then we have the thing that shakes him out of the nightmare is this line of soldiers that were waiting for them as his crew, his battalion, was advancing up a hill.

Then, this barrage, a very clear, very present gunfire, at least in our soundtrack. That’s the way I had it temped. That would be the thing that he will never forget.

This is what I was deciding and then showed it to Taylor. He said, “Yes.” It doesn't happen in a vacuum, but just pleasing myself on the first go around, this is what I decided.

That sound, that line of gunfire, would be something that he could hear very clearly for the rest of his life. Everything else, they're the details that go away. That sequence was constructed based on what my impression of his memory would be.

Memory and the retelling of things and how we're able to retell them what we remember. It's like the game of telephone. The message is one thing and then it goes through and it ends up as another.

You just don't tell the stories of your life the way they actually happen. Nobody does. But you remember certain things forever. Going back to the day my daughter was born, for instance, I don't remember a lot, but I remember the first time I heard her cry. I will never forget that as long as I live.

So if you’re cutting that, you use no sync until the crying starts.No sound. And then the crying happens and then, yep, I will never forget that ever.

I could tell you right now what it sounded like ‘cause I was so relieved. That's that moment when you have a kid and the doctors are there and they all just wanna make sure that she cries the first time. That's just the way that I decided to do that.

I’ve used that stylistically a number of times in Yellowstone. We did it, some of the stuff with Kasey when he was remembering a battle that he was in.

It's interesting to make choices about what a character would've taken away from a moment in their life and then that's what you share with the audience. Just as the character has to fill in the blanks around it for themselves, the audience does as well.

To me, it hopefully helps with an audience's engagement. When you see in that sequence that you're talking about, we just have this white and there's nothing in it, and then these bayonets come into frame. You say, “Oh crap! What's happening? Okay, this is a civil war battle.” Then, you start to hear little booms in the distance and hopefully it just sucks you in.

If I tell you what I think all of that sounded like, then you know, okay, that's a battle. I've heard a million battles in movies and TV shows.

I didn't pioneer this technique. I'm not trying to say that I'm doing something that's never been done, but I think it is fun to let the audience fill in as many of the blanks as possible. I just think it goes to their engagement of the story. At least, I hope it does.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

Yeah, that's probably my favorite sequence in the whole show.

It's stunning.Thank you.

Tell me about making that. Was it meant to be intercut the whole time or was it that they cross the river, then she plays the piano? They're two separate scenes.We had it every which way. We took two days to shoot that and we had five cameras. We had that river crossing shot just as a straight sequence. Somewhere in my Avid is a version of that that is just a straight telling of that story, like an 8-minute sequence of them crossing the river and all the complications.

And then separately, we had Elsa playing the piano in front of Ennis. We had those things as separate sequences complete. We could have played them back to back. We could have done it very straightforward.

The idea that I had — and it turns out Taylor had this exact idea, he just hadn't told me about it — was what if we could tie these two things together? Because what's happening emotionally at that part of the story is that all these characters are experiencing loss in different ways.

That’s the reason the piano’s in the middle of the prairie, right?Yep. Someone had to abandon it and Elsa has come across it and you get the sense that she's played a little piano in her life ‘cause she's competent enough. By the way, that is Isabel May. Every note of that is her on set that day.

That’s amazing!It is amazing because she also gives that performance.

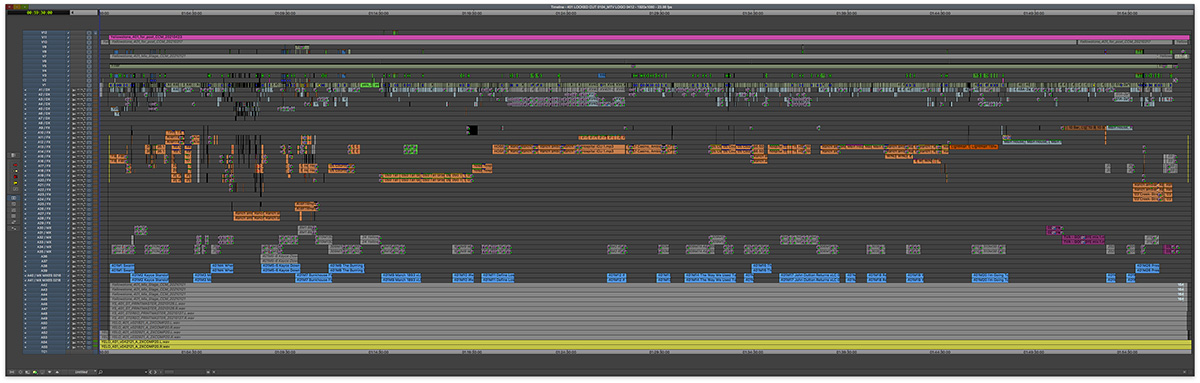

1823, Timeline for #104 - The Crossing

1823, Timeline for #104 - The Crossing

I've never seen anything like it, Steve. She did it six or seven times and each time you just watch the whole thing and she goes on that journey every single time. It is quite literally, I think, the most remarkable thing I've ever seen. She's playing the piano.

I was on set a lot for that show. It was ‘cause Taylor was on set a lot. I would go to him and we'd work and then we would show cuts to the actors when he wanted to.

I made the point of telling her. I said, this is all your performance. We didn't do anything because then, it became a badge of honor. We didn't touch it. We had the two separate sequences and then, loss became the unifying element. We've got the people crossing the river and some people are dying or they're losing horses and their belongings.

Elsa is geographically removed from that scene, right? She knows that they're out there, but she doesn't know that people are crossing the river and dying. She's experiencing the loss of the life that she lived before.

When they come across the piano, they say, “Do you play?” She says, “I do,” and then she thinks about it and she says, “I did. I'm not sure.” I guess I don't play anymore because I'm not gonna have that chance is the subtext. She starts playing and it's her thinking about everything that she has given up to be where she is right now.

Using that as the foundation for the loss that all of these characters are experiencing in different ways, I think it just worked. That idea that Taylor had originally had and that I had sort of separately stumbled upon just worked. Then, it became what is aligning her experience and her over the scene progressively breaks down and then we're seeing things go to hell in the river.

Just finding little ways to come in and out of those various stories. We see Margaret, Faith Hill's character, screaming. Again, we don't hear the sound. The only sound is the piano. The piano tells us the entire story.

I certainly temped without anything else. I think we maybe added a little bit of detail, sound detail, here and there. But we just let that piano and the sound of her starting to cry — that was part of it as well. It's a really important part of it and then you're seeing the images of the people.

That cut hardly changed from the first pass at it. It changed a little bit, but it was one of those beautiful things that clicked.

You have this idea, you write it on the page, you shoot it, you hope that we could do it this way. You protected yourself every which way in case it didn't work. But then it just worked. In a very gratifying way, a lot of folks have mentioned to me that that's one of their favorite sequences.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

Yeah. She kind of chuckles and says, “I never have much use for the happy ones.”

That’s an editorial decision, actually. You could cut that line out. You could not have him say that line, and that’s an editorial decision.It is an editorial decision, but there was something about the release of that felt right. When you're doing something that intense, you're always teetering on the edge of melodrama, I think, a little bit.

The most desperate sad stories that you've ever watched in film and television, you have to have moments of humor to break things up. It's the dynamics that we were talking about earlier. You've asked people to cry for about 3 and a half minutes and a lot of 'em do.

Then, you just release that tension and it's a way of saying “thank you, thank you for going along this journey with us.” I think it just keeps it grounded in reality. It was actually a very logical thing for that character to say in that moment.

Taylor's a pretty brilliant writer. That was written in and it was performed really well and Isabelle had the exact right reaction to it. It wasn't like the episode doesn't become uplifting after that.

She actually then travels and sees the devastation and sees her mother, who's just catatonic after having had to do what she did in the river, which is to kind of push off a woman that was drowning her. It’s this little moment. There's just little release and then we do it again.

Then, we see more sad stuff. Dynamics. It's a small dynamic. It’s mezzo piano to piano or whatever. It’s a little one, just a little lift, and then we give you more sad stuff.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

A little lift. Again, based in what feels like a truthful line of dialogue. If you just go back and look at that scene, it's two cowboys listening to this girl play a piano and watching her break down and sob.

They're watching her thinking, “What the hell's wrong with you? Can't you play something happy? We found a piano! This might be the last time we see a piano! Could we do something a little lighter?”

It was true to the experience of those three characters and then it becomes funny because you know of what's happening in both of those separate pieces. You as the audience know what's happening in the river and you know what's happening in the piano and you're watching thinking, “Good Lord” — the audience may be thinking this themselves — “Can't I watch something happy for a second?”

The cowboys say, “Don't you know any happy ones?” The audience is participating, thinking, that's what I want.

Yeah, she chuckles. Or she just smiles. It's a very honest reaction.It is a beautiful reaction and she's just an uncommonly, talented person. It was such a thrill to cut that show with her as the anchor for it.

All of ‘em. That was a very special experience. It was a very difficult show to put together. It was aggressive. We were out in trailers in the middle of North Texas and it was cold and everyone was in that environment — embedded, you might say — but it was a very rewarding project. To this point in my career: the most rewarding thing that I've been involved in and I'm very, very proud of it. A lot of things just came together in a way that you hope is gonna happen, but you don't know until you did it.

1923, Paramount+

1923, Paramount+

Episode one came out last Sunday. So episode one is out there in the world. It'll be every Sunday after that for eight weeks. So episode two is actually weirdly Christmas day and then episode three is New Year's Day.

It's kind of like this old Hollywood feel that I really love. Although it's another Dutton family story, it’s got its own very unique flavor to me.

And editorially, what was guiding you? How is this show different editorially — and why — from 1883 or Yellowstone?I think it's really the time period. When you think about movies that you've seen of that era or you think about that time in Hollywood, there's a scope and a sweep to it and a romanticism of it. That stuff has been designed into the visual storytelling of the show. I think then, editorially, it's just about honoring that and the music that we're using, it's big sweeping stuff.

We're in Africa in 1923 which has its own beautiful landscape and characteristics and animals. In the 1920s, what was happening there? They were building railroads. There was this height of British colonialism and people tried turning that into a tourist destination where they wanted to just hover above it all.

You have these different class things at work. It's just a very rich, very rich, tapestry. The costumes, the production design, all of it. You're trying to show people a world they may have seen, they haven't seen it in a while, and I don't think they've seen it like this.

There's a lot of scope to it, so you wanna honor the scope. One of the favorite things I'd say to my people if I’m giving them notes or something is: “The money's in the wides.” You wanna show those wide shots because that's where you can tell what we've done. When you have the kind of scope — and this is true of Yellowstone, 1883, and certainly true in 1923 — that scope becomes its own character.

1923, Paramount+

1923, Paramount+

In Yellowstone, the mountains, the wides, the aerials — they're all these things. That's what they're fighting. You don't have to be thinking about it consciously, but this is what's at stake. This land, this is what everybody wants.

We remind the audience or just check in with it, like, “Oh my God! That's beautiful. If that was mine, I would defend it as well.”

Again, subconsciously, maybe people think that, maybe not, I don't know. But it has its very important place in the structure of those shows.

In 1883, it's certainly that. The environments became this character that is swallowing up our travelers and killing them ruthlessly, through the elements or through the various things that happen when you are on a wagon train trying to move across the country in the 1880s. The land wins a lot of those battles.

Making sure that we checked in on the visuals and then we see over the latter episodes, the snow starts coming in and you think, “Man, if I was in the middle of nowhere and I saw those snow cover mountains, I would just think, ‘No way.’ There's no way I could make it through that.”

It becomes very scary and it becomes almost a villain, the elements that are closing it all around you and swallowing you up. You get high and wide and you see how tiny these people are and they're placed in this environment. “Oh my God! How are they gonna survive?” They don't have anything.

1883, Paramount+

1883, Paramount+

No road, no nothing. I think it's common to Taylor's work — to these stories, to this Yellowstone world — that it's about that. It's about characters learning to interact with the land and learning to live on it and with it.

It's very much about the indigenous people who were already here and who had figured all those things out and then have these intruders coming in. We service that all the time. It was just always in the back of my mind. Is there a moment where we can just kind of check in and see the landscape for a moment? Does it fit?

In doing that, it's just this little constant reminder and serves a different purpose in the three shows. It has a different meaning, I think, in the three shows, but collectively, it is what these shows are about. It's about our character's relationship with the land and learning to live with it and trying to survive.

Chad, thank you so much for spending some time with me.Oh, my pleasure.

A huge amount of great stuff, I think, came out of this interview, and hopefully, we’ll help aspiring editors.Oh, thank you. I just start talking and I hope any of it makes sense.

It all made sense, and it was very helpful and very useful information.Great. I'm glad to hear that. It's a pleasure, Steve. I've been listening to your podcast for a long time. I'm very honored to be a part of it, so thank you.